Home » 2014 (Page 3)

Yearly Archives: 2014

Fossil Friday

Were you able to identify Monday’s fossil? Allie Valtakis was. Find out after the picture what it is. I hope it doesn’t make your weekend too crappy.

These two things are coprolites, otherwise known as fossil poop. Always a hit with kids when I show them in schools, but I always get the same questions. Do they smell? Will I get poop on my hands if I touch it? Most are tentatively reassured when I inform them that to be considered a coprolite, the poop has to be replaced with mineral. After a long period of time, there isn’t any actual poop left.

Coprolites can be quite informative. Coprolites preserve traces of what the animal that left it ate, so they can be useful for looking at the diet of prehistoric animals. Karen Chin, a curator at the Colorado University Museum at Boulder, is the leading expert on coprolites, particularly dinosaur coprolites. She found wood In some coprolites found in the Two Medicine Formation in Wyoming, which is unusual for two reasons. One, most coprolites are from carnivores, so herbivore coprolites are relatively rare. Secondly, most herbivores don’t eat wood except as a last resort when no other food sources are available. She was able to tentatively attribute these coprolites to the hadrosaur called Maiasaura (mainly due to the size and content of the coprolites, and the abundance of maiasaur bones in the area), making this the first dinosaur known to eat wood, as well as giving a unexpected perspective on the lifestyles of these “duck-billed” dinosaurs.

Probably the most famous coprolites known are also from the Two Medicine Formation and were also studied by Dr. Chin. They were uncommonly large and clearly from a carnivore. The only known carnivore from that formation big enough to create such a ponderous poop was Tyrannosaurus rex himself.

These coprolites told a fascinating story. The coprolites were readily identified as being from a carnivore due to elevated levels of phosphorus, which results from eating a high protein (i.e. meat) diet. The coprolites contained numerous bone chips, indicating that T. rex was not a dainty eater. T. rex had a massively built skull with powerful jaws, providing T. rex with the most powerful bite of any terrestrial animal. It put these jaws to use chomping through a carcass, bone and all. If one compares the thick, broad teeth of a tyrannosaur with the flatter, blade-like teeth and lighter skull of an allosaur, it is clear they had fundamentally different niches and eating styles.

There was bigger surprise found in the tyrannosaur coprolites. Dr. Chin found traces of undigested muscle. Obviously, it was not original muscle left in the coprolites, but mineralized remains. Why is this important? Modern reptiles have a slow metabolism. Food takes a long time to go through the digestive tract. As a result, digestion is phenomenally thorough. Crocodilians can take the enamel off teeth. Mammals, on the other hand, have notoriously inefficient digestive tracts. It is not uncommon to find recognizable bits left in the feces. Because of the elevated metabolism, food simply passes through too quickly for digestion to be complete. Meat is far easier to digest than plant matter, so carnivores, even mammalian carnivores, typically do a good job of digestion. To have traces of undigested muscle in the coprolite of a T. rex means that either the tyrannosaur was terribly sick with a bad case of the runs, or more likely, tyrannosaurs had short digestive times and a high metabolism to go along with it. It is possible to have thorough digestion with a high metabolism, but it is much harder to have incomplete digestion in a carnivore with a low metabolism.

Thus, coprolites not only tell us about the diet of extinct animals, they can also tell us about their physiology.

On the preservation side of things, one may ask how something as soft and squishy as a poop can fossilize. The answer to that is not easily. The vast majority of poops get washed away. But fecal material does have some advantages that help them get mineralized. As I stated earlier, carnivore feces is enriched in phosphorus. Phosphorus is an important nutrient, eagerly sought after by many organisms because it is not all that common in the environment, making it what is known as a limiting resource.

The other advantage is that feces is mostly made of bacteria, not really waste products. Our intestines are populated with microbes without which we can’t digest our food very well. The richer foods we eat, the more the microbes can grow and meat is a very rich food source.So why is having bacteria in the feces an advantage? Because the waste products they give off during their metabolic processes cause minerals to precipitate around them. Those bacteria are in a phenomenally rich food source in the poop, so they are growing like crazy, which means they are also precipitating minerals like crazy. In effect, they fossilize the poop while they are trying to eat it. If the poop can stay together, is not disturbed, and there is sufficient water around to allow the continued growth of the microbes, you will get a coprolite. The problem with this of course, is that poops are rarely left alone. Other animals eat them, dung beetles carry them off, they get stepped on and spread about, and rain washes them away.

If you have a kid interested in learning more about coprolites, I recommend the book Dino Dung, by Karen Chin. The book is written for elementary school kids, but is packed with a lot of good information on the study of coprolites and provides a great introduction to the study of fossil poop.

If you have a kid interested in learning more about coprolites, I recommend the book Dino Dung, by Karen Chin. The book is written for elementary school kids, but is packed with a lot of good information on the study of coprolites and provides a great introduction to the study of fossil poop.

Stepping into a Belated Fossil Friday

Were you able to figure out what last Monday’s fossil was? It is on display at Mid-America Museum in Hot Springs, AR. Ordinarily this would have been posted last Friday, but real life intervened. Apologies for that. Part of what happened was that when I posted the original picture last Monday, I thought I understood the background behind the fossil. It turns out that new research was published in 2013 that changed a lot of the more detailed interpretations. It didn’t change anything of importance to anyone not obsessed with details, but it sent me on a three day search for answers.

What we are looking at here is a foot print of a sauropod. Sauropods were herbivorous, long-necked dinosaurs and were the biggest animals to ever walk the earth, some of them possibly massing 50-80 tons and stretching well over 30 m (100 feet). We can’t say exactly which one made this particular footprint, but we can take a pretty good guess. If you guessed Sauroposeidon, or Astrodon, or Pleurocoelus, or Paluxysaurus, or Astrophocaudia, or Cedarosaurus, you are at least partially correct. These are all titanosaurs, a subgroup of sauropods. But which one we call it is more problematic. It is usually almost impossible to tell exactly which species made a particular track and in this case, it gets even harder because there isn’t a lot of agreement over which names are even valid.

Before we get into that morass, what is a titanosaur anyway? Titanosaurs have been in the news recently with the discovery of Dreadnoughtus. Most people are familiar with Diplodocus and Brachiosaurus, the two iconic sauropods. These two dinosaurs are the best known representatives of the two main groups of sauropods, with many species in each group. Diplodocus had shorter front legs than back legs and was relatively thin with a long, whip-like tail. It’s head was small and elongate, with simple, peg-like teeth in the front of the jaws. Brachiosaurus had longer legs in front than in back and was stockier, with a shorter, stubbier tail. It’s head was larger, with spoon-shaped teeth. Titanosaurs had front legs that were roughly the same length as the back legs, with a relatively whip-like tail like Diplodocus, although not thought to be as long. The heads looked like Brachiosaurus, but more elongate. Some had teeth like Diplodocus, some like Brachiosaurus. Basically, if you try to envision an intermediate form between Brachiosaurus and Diplodocus, you would wind up with something that looked like a titanosaur, which is rather interesting because all the studies trying to figure out their relationships place titanosaurs as much more closely related to brachiosaurs than to diplodocids. In fact, titanosaurs likely evolved from early brachiosaurids, which means that all the characteristics that make them look sort of like diplodocids are examples of convergent evolution, if the hypotheses about their relationships are correct.

Before we get into that morass, what is a titanosaur anyway? Titanosaurs have been in the news recently with the discovery of Dreadnoughtus. Most people are familiar with Diplodocus and Brachiosaurus, the two iconic sauropods. These two dinosaurs are the best known representatives of the two main groups of sauropods, with many species in each group. Diplodocus had shorter front legs than back legs and was relatively thin with a long, whip-like tail. It’s head was small and elongate, with simple, peg-like teeth in the front of the jaws. Brachiosaurus had longer legs in front than in back and was stockier, with a shorter, stubbier tail. It’s head was larger, with spoon-shaped teeth. Titanosaurs had front legs that were roughly the same length as the back legs, with a relatively whip-like tail like Diplodocus, although not thought to be as long. The heads looked like Brachiosaurus, but more elongate. Some had teeth like Diplodocus, some like Brachiosaurus. Basically, if you try to envision an intermediate form between Brachiosaurus and Diplodocus, you would wind up with something that looked like a titanosaur, which is rather interesting because all the studies trying to figure out their relationships place titanosaurs as much more closely related to brachiosaurs than to diplodocids. In fact, titanosaurs likely evolved from early brachiosaurids, which means that all the characteristics that make them look sort of like diplodocids are examples of convergent evolution, if the hypotheses about their relationships are correct.

What’s in a name?

Now that we know basically what we are looking at, what do we call the one which may have made this track? That is an excellent question. Two different trackways have been found in Arkansas, both in a commercial quarry in Howard County. They were fantastic finds, with thousands of tracks (5-10,000 tracks in the first trackway alone), placing them among the biggest dinosaur trackways ever found. Unfortunately, other than a few tracks that were spared, they no longer exist as they were destroyed by the quarry operations. That is a sad loss for paleontology, but in defense of the quarry owners, the tracks were found on private land and the owners had no legal requirement to tell anyone about them at all, they are running a business after all. They allowed scientists to study the trackways and in the case of the second trackway, they approached scientists at the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville about the tracks on their own initiative, giving them the opportunity to study the tracks before they were destroyed. As a result, careful maps were drawn, some tracks were removed and others were saved as casts. So the trackways themselves may be gone, but the knowledge of them is still with us and in the public domain.

The tracks were initially described as being from either Astrodon or Pleurocoelus, based on the fact that fossils from these dinosaurs have been identified in Oklahoma in rock units called the Antlers Formation, which is correlated with the Trinity Formation in southwest Arkansas. However, some researchers have concluded that the material upon which these names are based can not be reliably distinguished from any other titanosaur, so the names are what is called nomen dubium, literally dubious names. Pleuocoelus became what is commonly referred to as a junk taxon, which are used as a waste basket for material not identifiable as something else. In this case, when people found bits of a titanosaur in the southern United States they couldn’t identify, they said, it’s um…uh…Pleurocoelus? Pleurocoelus! Yeah! That’s the ticket! In 2013, Michael D’Emic published his research in which he found that part of the material identified as Pleurocoelus are really from two different sauropods called Cedarosaurus and Astrocaudia, and other parts are from a Texan sauropod called Paluxysaurus, leaving other bits unidentifiable as anything other than indeterminant titanosaur. Additionally, he found that Paluxysaurus was simply a juvenile form of Sauroposeidon, a giant sauropod known from four huge cervical (neck) vertebrae found in Oklahoma. So in conclusion, what can we say about the tracks? They were made by a titanosaurid sauropod.

Life’s a Beach

The first trackway was found by Jeff Pittman in 1983 while he was working in the quarry for his master’s degree at Southern Methodist University (SMU). The second set was found in 2011 by quarry workers, who brought it to the attention of Stephen Boss, a geologist at the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville. The tracks in the first trackway were 12-24″ across and were interpreted as being from from adult sauropods. The other trackway was more diverse, with tridactyl (three-toed) footprints attributed to the giant carnivorous dinosaur Acrocanthosaurus, as well as tetradactyl (four-toed) tracks which may have been made by a crocodilian of some sort. The pictures below are of the first trackway, taken by David Gillette, and can be found at his site discussing Seismosaurus.

The rocks in which both of the trackways were found is in what is called the DeQueen Limestone, a subunit of the Trinity Formation. These rocks were laid down in the Early Cretaceous about 115 to 120 million years ago. At the time, the shore of the Gulf Coast went through Arkansas, so much of southwest Arkansas was underwater. The DeQueen Limestome has thin layers of sandy limestone, many of which are quite fossiliferous, with oyster shells in abundance. There are also layers of limy clay and gypsum, indicating the air was fairly hot and dry. Stephen Boss likens the environment at the time to be similar to the Persian Gulf of today. So what we have is the coast of a very warm shallow sea. The dinosaurs appear to have been using the area as part of a migratory pathway. So while no bones of these dinosaurs have been found in Arkansas yet, we know they were here, so keep an eye out when you are fossil-hunting in southwest Arkansas. Who knows, you might find something bigger than you imagine.

Depiction of the environment during the formation of the trackway. Mark Hallett. http://www.columbia.edu/dlc/cup/gillette/gillette19.html

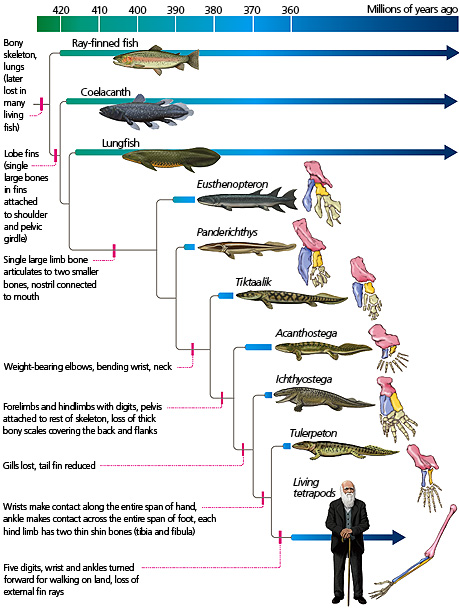

Myths and Misconceptions: The Transition From Water To Land Is Ridiculously Hard

It is commonplace to hear people say they do not accept evolution because they don’t see how some of the changes could have taken place. It’s just too complicated they say. What use is half a wing, they ask. As it turns out, the usefulness of half a wing, even a featherless baby wing, has been demonstrated, so that argument is out. Another transition people have difficulty with is the transition from water to land. Regardless of the fact that we have a good bit of fossil evidence demonstrating the transition, many people think that fins and feet are so radically different that they don’t see how it could have happened. Recent research has demonstrated in several ways that this transition is not nearly as hard as people might think, which may explain why it has happened multiple times in the history of life. For a truly bizarre history, one can look at the evolution of the elephants. Before they were elephants, they went from water to land back to the water, then back to the land.

So what tells us it really isn’t that hard? Let me introduce you to the robot salamander. This robot and its predecessors were designed to test different models of neural circuits involved in locomotion. What they found is that the same movements of the limb and torso allowed both swimming and walking. The only difference was the amount of resistance placed on the feet. Obviously, the ground supplied much more resistance to the limb motion than did the water. This caused a change in the neural signal, causing it to slow down and become stronger to account for the change in muscle power needed and the reduced speed of the movement. It was the same signal from the brain, it activated the same motor pathways. In other words, fish already had the neural pathways to be good salamanders.

Still, there are all the changes needed in the musculature and bones that surely had to be problematic. Research that has only recently been published indicates this isn’t hard either. Bichirs are a type of fish that regularly flops about on land and has true lungs. Emily Standen wanted to see what would happen if a bichir was raised on land and not free-swimming in the water. What they found was that the bichir changed how they crawled about, adopting a pattern that was more efficient. They held their heads higher off the ground and brought their fins closer to the body. More than simple behavioral changes, their skeletons changed as well. The supporting their pectoral fins changed subtly in ways that bore similarities with fossil of the earliest “fishapods”. It should also be noted that these experiments were on juvenile bichirs who were less than 70 days old and only lasted for eight months. This is not a lot of time to see differences.

I want to be clear that the bichir experiments do not show evolution of the fish. Evolution does not occur within a single individual. What we see here are epigenetic changes, not involving changes in the DNA. Epigenetic changes demonstrate developmental plasticity, the range over which a species can adapt to new environments without needing genetic alterations. But we now know that epigenetic changes can be passed on to the next generation in processes that are still only dimly understood. Unless these changes become incorporated into the DNA, they will fade if taken out of the environment that is producing the selection for that change. But eventually, these sorts of epigenetic changes can lead to real DNA changes that will lock in the change for all further descendants. In other words, what these experiments demonstrate is that fish already had the necessary developmental plasticity to evolve adaptations to land.

A rather extreme version of syndactyly. http://www.jisppd.com PMID: 21273726

As I stated, these sorts of changes have to be incorporated into the DNA, but surely that requires a lot of changes? There have to be a lot of genes that have to be changed radically, right? Turns out, no. The switch is rather simple and it doesn’t even involve changes to protein-producing genes. All it takes is a change in the regulation of those genes. Change the developmental timing, change the amount of a protein here or there, and you turn a fin into a limb. Fish and terrestrial animals use exactly the same genes to make fins and limbs. They just change how they use them. This is why you occasionally get people born with webbed hands and feet. It can even cause polydactyly, having more than the normal number of fingers or toes.

Left column shows the control animals showing normal fins. The right column shows the bichir raised on land. Standen et al. 2014.

A study published in 2012 looked at the regulation of hox genes, the genes involved in controlling the shape of our bodies, how our limbs are made, how many fingers we have, that sort of thing. All animals have them, they just vary in how many and how they are used. Renata Freitas and her associates took the control sequence for Hoxd13 from a mouse and put it into a zebrafish. The only thing this did was cause the Hoxd13 gene to be overexpressed. This caused the fish to have reduced fin tissue and the growth of cartilage forming what can best be described as a rudimentary limb. Just for emphasis, let’s say that again, simply changing the amount of protein created from this one gene turned a fin into a rudimentary limb. In other words, fish already had all the genes needed to make limbs for terrestrial locomotion.

So, we’ve seen that we have a lot of fossils documenting the shift from water to land. We’ve seen that fish already had the needed neural wiring to walk, the developmental plasticity to get started, and all the genes necessary. You can even see the transition showing up in the nerves that supply the human arm called the brachial plexus, the bane of medical students everywhere, which seems bizarre and nonsensical, until one looks at it from an evolutionary perspective. Then it all makes sense. But that is a topic for another day. All the transition really took was a prolonged stimulus that provided a selective advantage for walking around and limbs developed naturally from what was already pre-existing and working fine in the environment in which they evolved. Amazing how much change can be accomplished simply by a change in venue and a little push in the right direction.

Fossil Friday, Going Swimmingly

No one guessed what the fossil for this week was. Take a look at the image below and see if you can figure out who this vertebra belongs to before continuing on after the image. As you may have deduced from the title of the post, it is an aquatic animal.

This fossil is a really nice dorsal vertebra of a giant marine reptile. Most of the ones usually found in Arkansas are mosasaurs, but this one is different. It lived at the same time as the mosasaurs, placing it in the Late Cretaceous Period. As with all other Late Cretaceous fossils in Arkansas, it was found in the southwest corner. Specifically, it was found near Saratoga, Arkansas in Howard County by local resident Matt Smith. Interestingly, the very same spot has also turned up several nice mosasaur fossils, so it was a popular place in the Cretaceous seas. It shouldn’t be too surprising though, as it was a nearshore environment in a tropical climate much like the Bahamas today, so there would have been lots of good eating for hungry marine predators.

Ok, enough of the teasing. The vertebra we have here is that of a plesiosaur known as Elasmosaurus. These are classic marine reptiles that most people are familiar with to some degree. They have sometimes been described as looking like a snake that swallowed a sea turtle because of the relatively wide bodies with oar-like flippers and a very long neck. They are thought to have spent much of their time slowly cruising the seaways, using their long necks to catch fish unawares. some people have even suggestd that they floated at the surface of the water with their head out of the water, so that fish could not see it, allowing them to plunge their head down into the water and catch fish from above. That is pure speculation though. Right now there is no way to really test such hypotheses, so feeding methods remain in the realm of speculation until such time as someone figures out a way to test it adequately. At the moment, biomechanical tests indicate that either method would have been possible.

So if you find a vertebra like this, how do you tell whether it is a mosasaur or plesiosaur vertebra? They can both be large, although the one pictured here is the largest one I have ever seen found in Arkansas. The best way to tell is to look at the ends of the centrum, otherwise known as the body of the vertebra. Most of the time, that is all that is preserved, as all the processes that stick out have been broken off, like we see in this one. Plesiosaur vertebra have flat, possibly even slightly concave, or indented ends. Mosasaurs, on the other hand, have what is known as procoelous vertebrae, which have one end convex, a bit more rounded off. These differences make mosasaur vertebrae look more like over-sized lizard or croc vertebrae, whereas plesiosaur vertebebrae look more like the disc-like vertebrae seen in fish. This may mean that plesiosaurs were more adapted for aquatic life than mosasaurs. Both were clearly fully aquatic, what with neithr one of them having legs of any sort, but plesiosaurs appear to have been aquatic for longer, giving their spine to more fully adapt.

Indeed, when we look at the age of the rocks their fossils have been found, mosasaurs are restricted to the late Cretaceous, whereas the plesiosaurs first appeared all the way back in the Triassic (another successful prediction based on evolutionary theory). This means plesiosaurs had well over 100 million years advance on the mosasaurs. It didn’t really help them in the end though. About the time mosasaurs appeared, plesiosaurs were declining. Mosasaurs evolved and spread quickly, becoming the dominant marine predator of the Latest Cretaceous. Does this mean that mosasaurs outcompeted the plesiosaurs? Not necessarily. It has not yet been sufficiently determined whether or not mosasaurs simply filled a niche left open by the plesiosaur decline or competitively excluded them. there is also the argument to be made that they would not have competed at all. The body shapes of mosasaurs and plesiosaurs are quite different, indicating they filled different niches in the marine realm, so they weren’t going after the same food sources. Therefore, there is no particular reason we know of that they could not have existed alongside each other without adversely affecting each other.

Most people are familiar with them due to the much discussed “Loch Ness Monster”, which has often been said to be a supposed plesiosaur that has somehow survived for 70 million years. Of course, that idea doesn’t make a lot of sense for several reasons. It is highly unlikely that plesiosaurs could have lived for so long without leaving any trace of a fossil record. It does happen occasionally though. The coelacanth is a famous example of that, for a long time having a good 65 million year gap in their fossil record. They were thought to have gone extinct along with the dinosaurs until living specimens were caught. We know more about them now and their fossil record is no longer quite as limited as it once was, but it still has wide gaps in the fossil record. But more serious problems for Nessie arise from the fact that plesiosaurs were large, air-breathing marine reptiles. Coelacanths went unnoticed because they moved to the bottom of the sea, an option not available to plesiosaurs, which were limited to surface waters, and relatively shallow waters at that. That means they lived in exactly the sort of marine environments most visited by humans. That makes it hard for them to hide from people today and puts their bones in prime spots in the past to fossilize. Then of course, there is the problem that Loch Ness is a freshwater lake and plesiosaurs were adapted for saltwater. Not to say a species couldn’t have adapted for freshwater, but it does make it less likely. Finally, there would have to be enough plesiosaurs big enough to support a breeding population and there is simply no way they could all hide within the confines of a lake, especially since they have to live at the surface much of the time.

But what about the supposed bodies that have been found of plesiosaurs? They have all been identified as decomposing backing sharks. Basking sharks are one of the largest sharks known today. they are pretty harmless though, as they are filter feeders, much like the whale shark. When their bodies decompose, the jaws typically fall off pretty quickly. So what has been identified as the head of a “plesiosaur” was actually just the remaining portions of the cartilaginous skull without the large jaws. If you look at the picture of the asking shark here, there isn’t much left after you remove the jaws.

But what about the supposed bodies that have been found of plesiosaurs? They have all been identified as decomposing backing sharks. Basking sharks are one of the largest sharks known today. they are pretty harmless though, as they are filter feeders, much like the whale shark. When their bodies decompose, the jaws typically fall off pretty quickly. So what has been identified as the head of a “plesiosaur” was actually just the remaining portions of the cartilaginous skull without the large jaws. If you look at the picture of the asking shark here, there isn’t much left after you remove the jaws.

Next week is Labor Day on Monday, so I will likely not post a new fossil next week. I will post something next week, just not a mystery fossil. But there will definitely be one the following week, so please come back to see the next fossil and see if you can guess what it is before Friday. In the meantime, enjoy your vacation.

Mystery Monday Returns

Welcome back! the new school year has started for most, if not all, people by now. Everyone is busily trying to figure out new schedules, new curricula, new people, sometimes even new schools. Changes are everywhere this time of year. Paleoaerie is no exception. We didn’t get quite as much done over the summer as we would have liked (does anyone?), but it was an interesting summer, filled with good and bad. To start with the bad, the UALR web design course that was initially going to work on revamping the website is no more due to unexpected shakeups at the school. Nevertheless, a different course will take a look at the site and see what they can do, although they sadly won’t have as much time to deal with it.

But there was a lot of good that happened. Big news for Paleoaerie is that we are now partnered with the Arkansas STEM Coalition, a nonprofit advocacy group for STEM education within Arkansas. This is really important for us because this means Paleoaerie now operates as an official nonprofit organization. What does this mean for us and you? It means that any donation to the site is tax-deductible. It also means that many grants that we could not apply for before are now within possible reach. Fundraising should be a bit easier from now on, which means we may be able to do much more in the upcoming future. One of the things we will be doing in the near future is a Kickstarter campaign to buy a 3D laser scanner so that we can start adding 3D images of Arkansas fossils onto the website, which will be available for anyone to use. One might ask why not use some of the cheap or even free photographic methods that are available. In a word: resolution. I’ve tried other methods. When one is attempting to make a 3D image of an intricate object only a few centimeters across, they don’t work well. If you want details to show up, you need a better system. Stay tuned for that.

But there was a lot of good that happened. Big news for Paleoaerie is that we are now partnered with the Arkansas STEM Coalition, a nonprofit advocacy group for STEM education within Arkansas. This is really important for us because this means Paleoaerie now operates as an official nonprofit organization. What does this mean for us and you? It means that any donation to the site is tax-deductible. It also means that many grants that we could not apply for before are now within possible reach. Fundraising should be a bit easier from now on, which means we may be able to do much more in the upcoming future. One of the things we will be doing in the near future is a Kickstarter campaign to buy a 3D laser scanner so that we can start adding 3D images of Arkansas fossils onto the website, which will be available for anyone to use. One might ask why not use some of the cheap or even free photographic methods that are available. In a word: resolution. I’ve tried other methods. When one is attempting to make a 3D image of an intricate object only a few centimeters across, they don’t work well. If you want details to show up, you need a better system. Stay tuned for that.

Paleoaerie is also partnering with the Museum of Discovery and the University of Arkansas at Little Rock for a National Fossil Day event on October 11. Make sure to mark your calendars and come out to the museum to see the spectacle and diversity that can be found in Arkansas. There is much more than you think. We are also working with the museum on a new dinosaur traveling exhibit. It is very cool, so watch for it later this fall.

Paleoaerie is also partnering with the Museum of Discovery and the University of Arkansas at Little Rock for a National Fossil Day event on October 11. Make sure to mark your calendars and come out to the museum to see the spectacle and diversity that can be found in Arkansas. There is much more than you think. We are also working with the museum on a new dinosaur traveling exhibit. It is very cool, so watch for it later this fall.

The last big news that happened recently is today’s Mystery Monday fossil. Someone brought me a fossil to examine a couple of weeks ago. The first amazing part of it is that is was actually a fossil. the vast majority of what people show me are just interestingly shaped rocks. This was a bona fide fossil. Not only was it a fossil, but a really cool one. The image below is a vertebra from a little seen animal in Arkansas and not at all for a very long time. The fossil is roughly 100 million years old, putting it in the Cretaceous Period. At that time, Arkansas was on the shoreline of the late Cretaceous Interior Seaway. Take a look at the image below and see if you can figure out what it came from. I’ll let you know what it is Friday. Thanks to Matt Smith for bringing this wonderful fossil to my attention. Come out to the National Fossil Day event and see it for yourself.

Who Ya Gonna Call? Mythbusters?

Adam Savage and Jamie Hyneman of the Mythbusters do a great job of presenting commonly held myths and testing them in a variety of ways, trying and adjusting and retrying experiments. They even sometimes revisit myths with a new point of view and new questions. It is this that I think is the key to their success. They present science as a series of questions and experiments, revising and retesting, a dynamic process. Starting with what people believe and then presenting the evidence to show the real answer is an important part of the educational process. Derek Muller, who runs the Veritasium Youtube channel, did his PhD dissertation on just this topic, showing that simply providing the information did not increase learning. Unless the misconceptions the audience already held were first acknowledged and dealt with, people thought the material was clear and that they understood it, when in fact they had learned nothing at all.

All of this involves asking lots of questions. But what some teachers view as a downside to this approach (although it absolutely is not) is that invariably you will wind up with lots of questions you can’t answer. Your students will ask questions you have no idea what the answer might be. So what do you do in this case?

Hopefully, you already knew which of these options is the better choice. But where do you go to learn more? Some questions can be rather esoteric or have answers that can’t be easily looked up. Fortunately, hordes of scientists are at your beck and call to save the day. Here are four websites where you can ask real scientists any question you like. None of the scientists on these sites will do people’s homework for them, but are enthusiastic about answering questions.

Ask a Scientist has 30 scientists that will answer questions on biology, chemistry, physics, space, earth and environment, health, technology, and science careers. In addition, they have links to videos for some questions. You can look at answers to past questions and ask your own. Even though it is based in the United Kingdom, with all the scientists being from the U.K., they will answer questions from anyone.

Ask a Scientist has 30 scientists that will answer questions on biology, chemistry, physics, space, earth and environment, health, technology, and science careers. In addition, they have links to videos for some questions. You can look at answers to past questions and ask your own. Even though it is based in the United Kingdom, with all the scientists being from the U.K., they will answer questions from anyone.

This site is also based in the United Kingdom, but has scientists from all over the world. This site is limited to biology and paleontology, but it has over 100 scientists who can answer questions. Some are doctoral students, some are the tops in their field with decades of experience. All of them are experts in what they do and all of them are there to help. They have answered thousands of questions, all of which can be searched and read. If you don’t find what you are looking for, ask your own question. You might even find that you have started a lengthy discussion of your question between several experts, as has happened from time to time.

This Ask A Biologist is a National Science Foundation grantee and is hosted by Arizona State University. Again, it is limited to biology and is run by the biology faculty and graduate students of ASU. So on the one hand, you might think they might be more limited. But ASU has an extensive biology department and this site has much more ancillary material than most of the others. They have activities, stories,coloring pages, tons of images, videos, and links to other information. They have a teacher’s toolbox, providing easy searches for teachers to find exactly what they want, searchable by topic, activity, and grade level. In short, while they have several scientists available to answer questions, that is but one aspect of this educational site.

The Mad Sci Network has a huge amount of information. You can ask a question about anything. The site has experts from world class institutions available to answer questions. They have a searchable archive of over 36,000 questions already answered, so they may have already answered your question. In addition to the search features, they have several categories listed, in which you can pull up all the questions in those categories. They have a “Random Knowledge Generator” if you just want to have fun browsing at random. They also have a series of what they call “Mad Labs”, which are activities and experiments you can do at home or in the classroom. They have links to more information and resources elsewhere, including general science, educational methods and techniques, museums, science fairs, suppliers, and more.

So there you have it. When you are faced with questions you can’t answer, don’t try to bluff your way through. Who ya gonna call? Hundreds of scientists from around the world, that’s who.

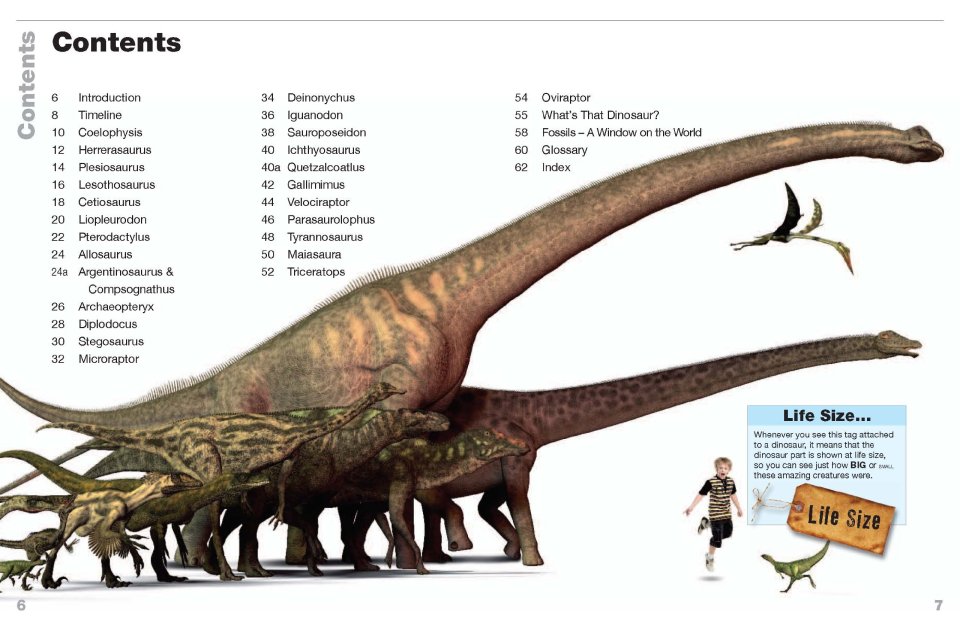

How Big Is Your Favorite Dinosaur? Find Out Here

Dinosaurs Life Size

By Darren Naish

Publication Date: 2010

Barrons Educational Series, Inc. ISBN: 978-0-7641-6378-4.

Author: Darren Naish is a well respected paleontologist publishing on all manner of dinosaurs, marine reptiles, pterosaurs, and other extinct animals. While he has published several notable scientific papers, he has also written extensively for the general public, ranging from children’s books to books for the educated layperson. In addition to this book, Naish published Dinosaur Record Breakers, another good book that kids will find interesting. He has also published on cryptozoology, the mostly pseudoscience study of “hidden” creatures, such as Bigfoot and the Loch Ness monster, debunking a variety of mythical creatures and discussing more plausible alternatives. You can also always find him at his highly regarded and widely read blog, Tetrapod Zoology, on the American Scientific blog network.

Author: Darren Naish is a well respected paleontologist publishing on all manner of dinosaurs, marine reptiles, pterosaurs, and other extinct animals. While he has published several notable scientific papers, he has also written extensively for the general public, ranging from children’s books to books for the educated layperson. In addition to this book, Naish published Dinosaur Record Breakers, another good book that kids will find interesting. He has also published on cryptozoology, the mostly pseudoscience study of “hidden” creatures, such as Bigfoot and the Loch Ness monster, debunking a variety of mythical creatures and discussing more plausible alternatives. You can also always find him at his highly regarded and widely read blog, Tetrapod Zoology, on the American Scientific blog network.

Dinosaurs Life Size came out a few years ago, but it is still a decent book for kids. I can’t say good for reasons discussed below, but it is better than many and has mostly good information. Don’t get it confused with the book of the same name by David Bergen, which came out in 2004. Naish’s book is much more up-to-date and scientifically accurate, having the advantage of having been written by an active researcher in the field who knows what he’s talking about. Not to criticize Bergen’s book as I haven’t read it, but if you were going to choose a book that was a decade old written by a non-expert or a book a few years old written by an expert who also happened to be a professional writer, which would you choose?

The book begins with a short introduction to dinosaurs and the book. A fold-out timeline follows, which puts all the animals discussed in the book in its appropriate place in time. The timeline includes a brief description of each period within the Mesozoic Era, commonly known as the Age of Dinosaurs. The meat of the book is a generally two page description of 26 different animals. Each animal gets a brief discussion of what it looked like, where it lived, and a few interesting factoids that have been pulled “from the bones” as a section for each animal is called.

Of course, the main draw of the book are the size comparisons. These are handled in two ways. Each animal is illustrated in full view alongside a young kid for scale. Almost all of them also have a drawing of a body part in real size, which really puts into glaring contrast just how big (and tiny) some of these animals were. Herrerosaurus has a hand, Lesothosaurus has its head for scale. At the extreme ends, Sauroposiedon has an eye and Argentinosaurus has a toe while Microraptor and Archaeopteryx are small enough to be drawn in their full glory. Most are covered in two facing pages, so that every turn of the page presents a new animal. A few are presented on fold-out pages, although I am unclear as to why because only one actually takes advantage of the extra space to present its animal. the other one just puts two animals instead of the standard one.

After the animal descriptions is a fold-out page with a dinosaur quiz to test the reader on what they learned. this is followed by a short discussion of what fossils are, how they are formed, how old they can be, how they are found, and a couple of famous fossil examples. The book ends with a glossary and index. All told, there is plenty of solid information for the young reader who will gaze in wonder at the dinosaurs and at least some will enjoy testing themselves on the quiz.

The book has good information. I particularly like the pictures of a globe marking where each one is found. The illustrations of the life size bits give a good indication of the actual size of the animal. I like the pictures of real fossils and the bits of information about what has been found through their study. The book is very visual and should appeal to kids. The book is listed as being most appropriate for kids in grades 2-6, which I think is a pretty fair assessment. Advanced readers in first and second grade will like it, but will be bored by it by the time they get out of elementary school, but most kids in the 3-5 grades will like the book.

I do, unfortunately have some serious complaints about the book. First and foremost, the book is called “Dinosaurs Life Size”. I would prefer books labeled as such stick with dinosaurs. Despite knowing better, Naish chose to include descriptions of Plesiosaurus, Stenopterygius, Liopleurodon, Pterodactylus, and Quetzalcoatlus; none of which happen to be dinosaurs. You may notice that this leaves only 21 actual dinosaurs. A better title would have been Mesozoic Reptiles Life Size, but I can understand that probably wouldn’t sell as well. Still, it is misleading. What I cannot forgive though, is that he does NOT clearly identify them as non-dinosaurs. This is such an unforgivable sin that I am tempted to tell people not to get this book. The only place he indicates they are not dinosaurs is ONE sentence in the introduction. Naish has published research on all of these animals, he certainly knows better, so this is unpardonable.

The next complaint I have is in the illustrations themselves. Some of the dinosaurs are noticeably absent of feathers. The Gallimimus is bare, except for a tuft at the top of its head. Part of this an be forgiven by the enormous advances that have been made due to new discoveries in the few short years since publication of the book. But even in 2010, we knew more dinosaurs were covered in feathers much more than is shown in this book. It is possible that feathers of some sort were an ancestral condition of ALL dinosaurs, so the bareness of some of these illustrations is wrong, even for the information he had at the time, so why the drawings were done this way is beyond me.

The last complaint I have is in the sizes. Each description is given a word description of how big each animal is. But the pictorial comparisons with the children are not the best. There is only a rough idea of how big the children are, which one is forced to base entirely on one’s experience with kids as there are no scale bars in any of the pictures. For a book about size, this is an inexcusable oversight. I have personally seen kids of a similar age who were between three feet and five feet. Now imagine extrapolating that difference to an animal that is thirty times that size and you can see the immense errors involved. Admittedly, there is a lot of uncertainty in the actual sizes of many of these animals (there are pretty much no complete sauropod tails, for instance, so determining length is problematic). But this book neither mentions anything about the uncertainties involved and then complicates the issue with further uncertainties in the illustrations while giving exact measurements in the written description.

So, in conclusion, I cannot fully support this book as there are too many serious problems. However, it is still better than many others on the market and does have solid information in the texts. The pictures give a rough idea of sizes, which for the age the book is geared towards is reasonable. But it is inconsistent with the sizes between the text and the illustrations; the illustrations themselves are not always accurate in terms of what we know about feather coverings, thus showing somewhat antiquated pictures of dinosaurs; and the book is really about Mesozoic reptiles, not dinosaurs anyway. Thus, the best I can do is give it maybe 3/5 stars, which pains me deeply because Darren Naish is a truly smart, well-read, and knowledgeable person who otherwise has written lots of great material.

6 Ways to Completely Fail at Scientific Thinking, Part III

All of the mistakes discussed so far are universal among humans to a greater or lesser degree. These last two are also universal and extremely common, leading to a world filled with pain and suffering, bigotry, and misunderstandings on a grand scale. I should warn you that this discussion will make many people uncomfortable because it cuts into the core of how people view themselves. People define themselves through the memories of their experiences and we tend to remember sound bites better than the complexities of reality, which makes for a dangerous combination.

5. We tend to oversimplify our thinking.

Of all of the mistakes, this one has most likely caused the most problems. When we were still living as hunter-gatherers in small bands, this was a benefit and can still be in some areas. When you live in an environment filled with potentially life-ending threats, you need to be able to recognize and react to them quickly. When that rustle in the bush may be a Smilodon about to attack, you can’t afford to think about all the different options because if you do, you are dead. But most of us no longer live in that sort of environment. We can take the time to think. We just have to fight our natural instincts that are hardwired into our brains. It’s tough, I realize that. It’s impossible to do all the time. But I hope you will see why it is so important that we try.

It is at the core of stereotypes and the “us vs. them” mentality that drives everyone to some extent. Any time you hear someone say, “Blacks are…,” or “Muslims are…,” or insert any group you want, that person is oversimplifying their thinking. It does not matter what you say after that first phrase, it will not accurately describe all members of that group. All “Blacks” are not actually black, nor do they share the same heritage, culture, language, or anything else. All those people that are thought of as Muslims by those using that stereotype are not in fact Muslim. I say this because almost invariably when non-Muslims refer to Muslims in a stereotypic fashion, they are confusing Arab (or anyone from the Middle East) and Muslim. Muslims and Arabs, like any large group, do not all share the same beliefs and culture.

In the first post in this series, I mentioned the anti-vaccine movement. It all started from ONE paper (since thoroughly discredited and debunked) that only referred to ONE specific vaccine. The whole point of the paper was to discredit that specific vaccine so the author could sell his own version. But no one in the anti-vaccine seems to remember that and they have simplified the topic to ALL vaccines.

In science, this sort of thinking causes people to read a single set of experiments (or even one experiment) on a specific target and then try to apply the result to everyone. This mistake is rampant in the medical field. A study will be published saying that a series of rats showed a result and instantly the media says that all humans will have the same result. Fortunately, scientists are well aware of the differences between rodents and humans. A result in rats and mice often does not carry over into humans. This is why all drugs have to go through human trials after they pass animal trials.

Even if a drug works in the small sample of humans, that sample is not truly representative of all humans. You may have heard that science has proven that vitamins are pointless and may even be harmful? The studies that indicated vitamins had no benefit were all done on healthy volunteers that mostly had good diets. So yes, if you are healthy and are getting everything you need from your diet, you don’t need vitamins and the excess can actually hurt you. Unfortunately, most people do not fall into this category, so for them, taking vitamins can indeed help. (This is just another example that eating right and having a healthy lifestyle will avoid many of the health problems most people have and will save you money in the long run. Exercise is almost always preferable to pills and is free.) Even healthy humans are incredibly variable and have different metabolisms. The same drug will not work the same on everyone.

All those internet memes you get with a picture of someone with a saying on it? Fabulous examples of oversimplification. The internet is full of examples of overly quick and thoughtless thinking. Here is a tip, if anyone can boil down the essence of a social problem with one pithy statement, it is almost guaranteed to be WRONG. I have heard more than one person say that because Muslims flew planes into the World Trade Centers, all Muslims were evil and should therefore all be killed, because “they all want to kill us anyway.” To any rational person, this statement is clearly, insanely, wrong. You may wonder why I have mentioned Muslims a few times. That is because right now, it is the most prevalent and dangerous stereotype I know and one which is very familiar to everyone. They either hold that view or know many who do.

I could go on and on about how people oversimplify for the rest of my life, but it gets seriously depressing rather quickly, so I will stop here. But I hope you get the point: Oversimplification, overgeneralizing, has led to the wrongful deaths of hundreds of millions of people and is the source of much of the hatred in the world. Be aware of just how common this mistake is and STOP DOING IT.

You how do you avoid this problem? Never take one study or one source as truth. It is ok to keep an open mind about something, but don’t put your faith into it unless you can verify it through other reliable sources. Wait for other studies that confirm the results because it may be that the first study was wrong. Avoid overgeneralizing. Just because something worked once, do not think it will work every time. Always, always, always keep the parameters of a study in mind, respect the limitations of any study. A result on one mouse in one situation has little to do with results from many people in all sorts of variable conditions. Do not extrapolate beyond the data without clearly understanding that the extrapolation is purely speculative guesswork and may not hold up in reality.

6. We have faulty memories.

One way that our memories are faulty is in that confirmatory bias discussed in the previous post. You can see this problem in everyone who gambles, be it at a casino or the stock market. Most people remember their successes far more commonly than their losses. People can lose fortunes this way. Casinos are masters at exploiting this mistake. If a gambler wins early, they tend to continue playing long after they have lost their winnings and more. Every time they win, they remember that one win and forget all the loses before that. Some people do the opposite, focusing on their failures and minimizing their successes, which leads to problems therapists deal with every day.

Science, particularly medical science, has a form of institutionalized faulty memory. It is much easier to publish positive results than negative ones. Therefore, experiments that didn’t work tend to be glossed over and forgotten, focusing on the ones that succeed. Of course, if those successes are due to chance or faulty experimental design, ignoring the negative results leads the whole field astray. How serious is the problem? A paper in 2012 found that only 6 out of 53 “landmark” papers in haemotology (study of blood) and oncology (cancer research) could be replicated. This sort of publication bias on the positive can have profound problems. It may sound like this means that science can’t be trusted, but what it really means is that it is critically important to never jump on the bandwagon and follow the advice of a new study. Wait until it can be confirmed by other research. Science is all about throwing hypotheses out there and testing them to see if they really work. One test doesn’t do it. Multiple tests are needed and you cannot forget the failures.

Where faulty memory really comes into play is in just how easy it is to change our memories. Simply hearing another person’s experiences can change our own. My favorite study showing this interviewed people about their experiences at Disney World. The participants watched an ad showing people interacting with Bugs Bunny at Disney World. The fact that this event is impossible (Bugs Bunny was not owned by Disney and so could not make an appearance at Disney World) did not keep many of the people from saying that they had fond memories of seeing Bugs Bunny at Disney World.

Kida discusses the results from some researchers in which they asked students where they were when they first heard of the space shuttle Challenger exploding. They asked shortly after the event and then again two and a half years later. Despite claiming that their memories were accurate, none of them were entirely accurate. Some of them were wildly off. Yet the students insisted that they were correct and disavowed the record of their earlier remembrance. There are several studies like this that say the same thing: our brains do not faithfully record our experiences and those memories change both over time and through suggestion by others.

So, what does this mean for us? It means that we have a bad habit of misattributing things, combining memories or making them up whole cloth. Criminal psychologists are deeply aware that eyewitness testimony is the least reliable evidence that can be brought into court, despite the fact that it is considered the most reliable by most people. People commonly say “I’ll believe it when I see it,” and “I saw it happen with my own two eyes!” We put a lot of stock into our perceptions and our memories. But, as is quite clear from decades of research, neither our perceptions or our memories are at all reliable.

So what are we to do if we can’t rely on our own experiences? Make records, take pictures, write it down. Compare experiences with other people. There is some truth to the now common statement; “Pics or it didn’t happen.”

Final thoughts

And so we conclude the introduction to the six basic errors in thinking we all make to a greater or lesser extent. These mistakes are universal, they happen repeatedly daily basis. Yet they have grave consequences. In science, we have ways to try to avoid them. We record data. We share it with others and let them try to poke holes in it. We do not trust only one example and demand verification. Scientists make these mistakes all the time. But by being aware of the mistakes and having procedures in place to deal with them, we can minimize the problems.