Basilosaurus, the Bone Crushing Whale That Was Mistaken For a Lizard

Last week we saw this vertebra and lower jaws of Basilosaurus.

The history of Basilosaurus is intimately tied to Arkansas. Alabama and Mississippi may have claimed Basilosaurus as their state fossil (and indeed the fossils are much more common in those states), but it was an Arkansan that found them. Judge Bry found some bones in the Louisiana portion of the Ouachita River in 1832 and sent them to Dr. Richard Harlan at the Philadelphia Museum. After examination of these bones, along with more bones sent by Judge Creagh from Alabama, Dr. Harlan noted similarities with plesiosaur vertebrae, only twice the size, so in 1834 he named the animal Basilosaurus, king of the reptiles.

In 1838, more bones were discovered in Arkansas, near Crowley’s Ridge. E. L. Palmer published a brief note on them in 1839. Meanwhile, Dr. Harlan had taken his bones to the United Kingdom to see the esteemed Sir Richard Owen, the most prominent paleontologist of his day (even today, he is considered one of the most important researchers in the field). Sir Owen found that the bones were not from a reptile at all, but from a whale. Therefore, he proposed changing the name to Zeuglodon. However, the rule of precedence requires the first name to take priority, so Basilosaurus it is.

Basilosaurus has an important place in the study of whale evolution. In addition to being the first primitive whale identified, Basilosaurus was the first true whale that was an obligate aquatic animal. Since its discovery, several other species have been found, but they all still retain enough limb function to move, however awkwardly, on land. Basilosaurus, due to its size and having no functional limbs other than some small flippers, would have been unable to move on land. As can be seen in the chart above, Basilosaurus was not the ancestor of modern whales, though. It appears that Dorudon, a close relative, had that honor.

Basilosaurus was a huge animal, reaching more than 15 m (50 feet). Neither it nor Dorudon had the forehead melon characteristic of modern cetaceans, which indicates it likely did not have echolocation, but did have very powerful jaws, clearly indicative of its carnivorous diet. A recent (this year) study found that Basilosaurus had an estimated bite force of 3,600 pounds, giving it the strongest jaws of any mammal yet measured.

FEA analysis of a Basilosaurus skull. Snively et al. 2015. http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0118380

There is a bit of a problem saying how old Basilosaurus is. The original fossils from 1832, as were the Arkansas fossils, were found in the Jackson Group, a series of intertidal to estuarine and shallow marine sediments of Eocene age, around 37-34 Mya. Another set of fossils from Crowley’s Ridge was found in 2008. However, according to marine mammal biochronology estimates, Basilosaurus should have appeared around 44 Mya. However, fossils do not generally record the first appearance of an organism. Thus, the most likely explanation is that Basilosaurus evolved roughly 7 My before the fossils we have found. The only way to solve this conundrum is to find more fossils, so get cracking.

Fossil Friday, A Whale of a Time

Were you able to figure out what the mystery fossil this week was?

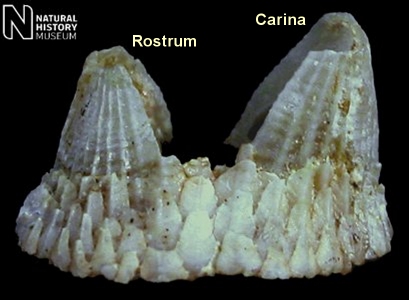

This is a vertebra, as I am sure most people could readily see. The two centra, the body of the vertebra, are flat to even a little concave, indicating an aquatic creature.

Here is a little more, showing pieces of the jaw.

Here is a picture by Karen Karr showing what the animal may have looked like when alive.

This is a Basilosaurus. The name means “king lizard”. It is an odd misnomer, though, because it is not a reptile at all. It is in fact a true whale, one of the first to have flippers rather than legs. Fossils of Basilosaurus have mostly been found in Alabama and a few other places in the southern United States, but the partial skeleton of one was found near Crowley’s Ridge in Arkansas.

An unexpected museum trip has presented itself to me, so this post will be short, but come back Monday for a more detailed discussion of Basilosaurus, the “bone crusher”.

Mystery Monday, Not a Fish Story

I have a new mystery fossil for you this week. I thought I would put a new fossil off until next week, but considering that next week is Spring Break for many around here and that new, cool research has been published on this animal recently, I decided to go ahead and put it out there.

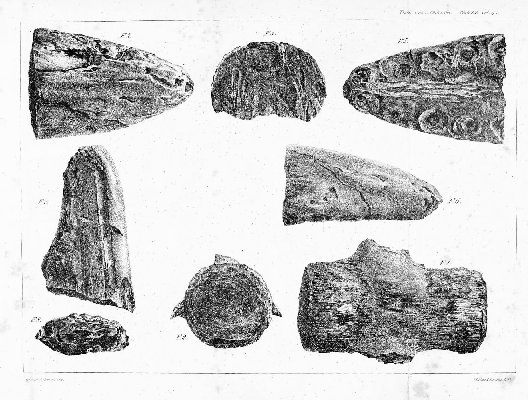

This is a drawing of the vertebra made by Sir Richard Owen, one of the greatest minds in paleontological taxonomy of the 19th century. The fossil had been identified as one thing, but Dr. Owen provided a thorough and convincing discussion of why that interpretation was wrong. The name given to it was rather humorously coincidental, considering what it turned out to be. It is difficult to identify isolated vertebrae, so I’ll give you another drawing of the same animal, but different parts.

This image is by the person who originally described the earlier vertebra, but also includes a few more pieces.

See if you can take the images, along with my clues, and figure out what this is. We’ll see if anyone can do better than the original descriptor.