Buffalo National River: Boone Formation

If you are looking for a great place to begin your canoeing experience, or just a quiet river to float down with great views, you can’t go wrong with the Buffalo National River in Arkansas as it flows through the Ozark and Boston Mountains. In 1972, Congress declared the Buffalo to be a National River, the first river to be so designated in the Unites States, which protects it from industrial use and any construction that might change the natural character of the river. It is renowned for its clean water and spectacular bluffs. People come from all over to camp in the park, hike its trails, and float the river. Much of the river is easy to float, so a welcome adventure for novices, although the upper reaches can be challenging.

This is the first of many posts about the geology of the river and the fossils that can be found in the park. Please note that this is a national park, so collecting fossils within the park boundaries is strictly prohibited. However, many of the formations discussed herein can be found throughout large portions of the Ozarks, so if you want to collect fossils, consult a geologic map and find a road that runs through the formation outside the park to find suitable roadcuts. Fossil collecting is allowed on state land, so just make sure you are not in a national park, national forest, or on someone’s private land (unless you have their permission).

AGS EWS-7. Stratigraphic column for upper Buffalo River

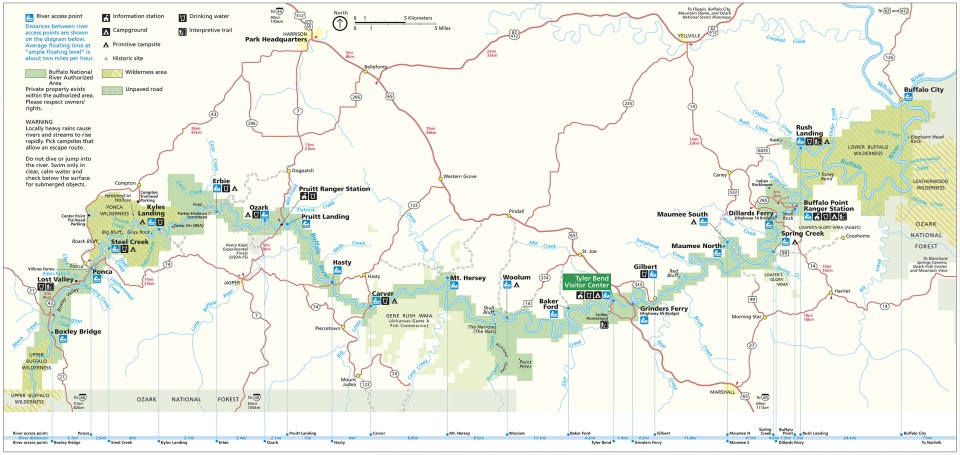

The Buffalo river cuts through several formations which are mostly Ordovician or Mississippian in age (~470 to 320 Mya). You can find geologic maps in pdf format of the Buffalo National River here and here.In the western reaches, the primary formation is the Everton Formation, but in the central and eastern portions of the river, the Boone Formation dominates. There are numerous bluffs displaying thick sections of the Boone.

The United States Geological Survey describes the Boone Formation as “mainly finely crystalline limestone with some cherty limestone and interbedded chert and minor shale. Approximately 400 ft. maximum thickness.” There is a lot of limestone in the Ozarks, but the nodules and thin beds of chert make the Boone stand out from the others.

It is early Mississippian in age, although exactly how old is a bit debateable. The USGS lists it as being in the Meramecian/Osagean stages, which places it mostly in the Middle Missippian. However, the Arkansas Geological Survey says it is in the Kinderhookian/Osagean stages, which are mostly early Mississippian. These stages are regional North American names, so you won’t find them on standard geological time scales meant to be used globally. At any rate, the Boone formed approximately 340-359 million years ago.

During the Paleozoic Era, the ocean had several cycles of raising and lowering sea levels. During the time the Boone Formation was forming, the region was a near shore marine environment, which explains the limestone and shale. The chert has typically been ascribed a biogenic origin, possibly the result of blooms of diatoms and radiolarians, both of which are single-celled organisms that make shells from silica, rather than the more common calcium carbonate which helped form the limestone. These organisms have also been presumed to form the Arkansas novaculite, a formation of metamorphosed microcrystalline quartz that reaches up to 900 feet in thickness. However, recent work indicates that both the Boone chert and the novaculite were formed from volcanic ash, created by an island-arc volcanic chain that existed about where the Ouachita Mountains are today.

“Honeycombed” rocks seen along the Buffalo. NPS, Buffalo National River.

Northern Arkansas is known for its widespread karst topography, meaning it has a lot of sinkholes and caves, most of which are in the Boone Formation. The cave systems are so extensive that at periods of very low flow, the entire Buffalo River is swallowed up and becomes subterranean in a few areas. The Boone forms the ceiling of the most famous cave in Arkansas, Blanchard Springs Caverns, which are well worth visiting if you find yourself in northwest Arkansas. On a side note, you may find references to the Boone in Blanchard Springs being as young as 310 million years old, but with better refinement of dating techniques and better dating of the rocks, that date has been pushed back.

The next posts in this series will cover the fossils that have been found in the Boone Formation. Stay tuned.