Home » Reviews (Page 4)

Category Archives: Reviews

Life is one big family

Teaching how all life is interrelated is a whole lot easier if you can show something akin to a family tree for living organisms. The Paleobiology Database has all the fossils organized by taxonomic relationships to help you find things in the database, but it is not very useful for visualizations. The Encyclopedia of Life has lot of information and multimedia available for over a million individual species and shows how they are classified and is quite useful if one is looking for information on a particular species. But again, it is not very visual.

Teaching how all life is interrelated is a whole lot easier if you can show something akin to a family tree for living organisms. The Paleobiology Database has all the fossils organized by taxonomic relationships to help you find things in the database, but it is not very useful for visualizations. The Encyclopedia of Life has lot of information and multimedia available for over a million individual species and shows how they are classified and is quite useful if one is looking for information on a particular species. But again, it is not very visual.

The Tree of Life website is an excellent website providing a great deal of information on phylogenetic relationships (for good discussion of phylogenetics, try here and here), providing abundant references on the primary literature discussing how scientists think various organisms are related. They work in collaboration with the Encyclopedia of Life, with the EOL focusing on species pages and TOL focusing on relationships. On TOL, one can start at the base of the tree and click on various branches following different groups into smaller and smaller groups, with each page providing what groups are descended from the starting group. For instance, the base of the tree starts with links to eubacteria, eukaryotes, and archaea, with viruses with a question mark. Each one is hyperlinked to a page discussing relationships within that group. It also provides a discussion of possible alternative branchings as well. Thus, the relationships are not presented as “we know this to be true,” but as an active, ongoing process of discovery and research. It is often highly technical, but would be extremely useful for high school students working on an evolutionary or biodiversity topic.

The Tree of Life and the Encyclopedia of Life are great sources for information on species and their phylogenetic relationships, but if you want better visualizations of the sum total of biodiversity, there are other websites that are definitely worth your time.

The first I would like to mention is the Tree of Life interactive by the Wellcome Trust and BBC. Watch the great video with David Attenborough first, then dive into the tree itself. The tree simplifies life to about 100 representative species. It is seriously weighted toward mammals, so provides a very skewed version of biodiversity, but the presentation should appeal to those who are most interested in the overall development from bacteria to humans. If once clicks on any individual species, it highlights the path to the base of the tree and provides a text description and in some cases pictures, a video, and locations. Click on another species and the path to the last common ancestor of the two selected species is highlighted. All the files are open source and available for free download, including the images and videos.

Another interesting site is the Time Tree. This site has a poster that shows 1610 families of organisms available for free download. The poster does a better job of showing the true diversity, but is still heavily weighted towards eukaryotes. However, the real purpose of the site is to provide divergence dates between two species. Simply type in two species names using either scientific (say, Homo sapiens and Gallus gallus) or common name (say, human and chicken) and it will provide how long ago their last common ancestor lived. It should be noted here that the dates listed are estimates based on molecular data. They should not be considered as conclusive dates or anywhere near as precise as listed. Indeed, the value given is a mean value of several estimates, with the median value also given, as well as what they call an “expert result” (which they sadly do not explain). In addition, they provide the scientific references the results came from and the dates provided for each, which can be quite broad. In the example above, those values range from 196.5 to 328.4 million years ago, but of the nine studies listed, all but two fall within 317.9 and 328.4 million years ago. There is also a mobile version of the site, as well as an iPhone/iPad app, as well as a book.

Another interesting site is the Time Tree. This site has a poster that shows 1610 families of organisms available for free download. The poster does a better job of showing the true diversity, but is still heavily weighted towards eukaryotes. However, the real purpose of the site is to provide divergence dates between two species. Simply type in two species names using either scientific (say, Homo sapiens and Gallus gallus) or common name (say, human and chicken) and it will provide how long ago their last common ancestor lived. It should be noted here that the dates listed are estimates based on molecular data. They should not be considered as conclusive dates or anywhere near as precise as listed. Indeed, the value given is a mean value of several estimates, with the median value also given, as well as what they call an “expert result” (which they sadly do not explain). In addition, they provide the scientific references the results came from and the dates provided for each, which can be quite broad. In the example above, those values range from 196.5 to 328.4 million years ago, but of the nine studies listed, all but two fall within 317.9 and 328.4 million years ago. There is also a mobile version of the site, as well as an iPhone/iPad app, as well as a book.

Another site of interest is Evogeneao.com. They have an interesting Great Tree of Life, as they call it, which like most others is heavily weighted toward eukaryotes. They have good explanations of evolution, along with a set of resources for teachers, including an interesting suggestion for how to introduce evolution to students. The interesting part of this site is their discussion of evolutionary genealogy, in which they extend the idea of a family tree farther back than it typically seen. They provide methods to calculate how far removed you are from other species. You can pick from a list of animals and it will tell you how closely you are related. For instance, choosing dolphin returns an estimate of 27 millionth cousin, 9 million times removed. That nicely encapsulates not only the idea of relatedness, but the immense scales of time we are talking about.

The Interactive Tree of Life, or iTOL, is another interesting site that may be of interest to high school teachers. This site utilizes genomic data as the basis of its trees and, unlike the others, provides a better visual indicating how truly diverse prokaryotes are in relation to us. It also allows you to print out phylogenetic trees in different formats, depending on your preferences and what sort of information you want to display. You can even upload your own data if you wish, but most teachers will likely choose to stick with the displays already provided, as there are simpler programs to deal with trees that any but the most precocious senior high school student (or college student for that matter) may wish to create.

The Interactive Tree of Life, or iTOL, is another interesting site that may be of interest to high school teachers. This site utilizes genomic data as the basis of its trees and, unlike the others, provides a better visual indicating how truly diverse prokaryotes are in relation to us. It also allows you to print out phylogenetic trees in different formats, depending on your preferences and what sort of information you want to display. You can even upload your own data if you wish, but most teachers will likely choose to stick with the displays already provided, as there are simpler programs to deal with trees that any but the most precocious senior high school student (or college student for that matter) may wish to create.

There are a few other interactive trees out there that may be more appropriate to younger viewers. One is at the London Natural History Museum website. This one is very simplistic, having only sixteen branches, with four of them being primates, but it gets the point across. This interactive is limited to providing the link between any two branches and the name of the group containing both. For instance, clicking on the banana and the butterfly gives the name Eukaryota. Another site provides an interactive for the poster Charles Darwin’s Tree of Life. This interactive allows one to zoom in on any part of the tree and if one clicks on an animal, a short description of the animal is provided. Sadly, the two best interactives I have yet seen are not available on the internet. I had the opportunity to explore DeepTree at the Harvard Natural History Museum and it is truly spectacular, as is their FloTree. If you get a chance to see them, you should. Hopefully, one day they will be available in a broader format than now.

All of this assumes of course, that people actually know how to read these trees, which is a false assumption in that most people really do not. So it would be useful to spend some time getting familiar with proper interpretation of them before using them in class. There are several resources explaining this (such as here and a really excellent video here), so I will not put a tutorial on here unless there are requests to do so.

All images posted here are from the websites being discussed and are copyrighted to them.

You were here: Maps for seeing geography through time

It may seem that the earth is pretty stable. You can always count on the mountains being there when you look for them. But the Earth is a dynamic place. Volcanoes, floods, landslides, and earthquakes all change the landscape in ways we can see quickly. What we don’t typically see is that if we expand these processes over long periods of time, those same processes alter the landscape far beyond our experiences. The surface of the Earth is covered in a crust broken up into numerous plates, which are constantly shifting and moving. The plates only move between 2.5 – 15 cm/year (the previous link contains information on how this is measured and provides activities for teachers for use in the classroom), but add this up over millions of years and the Earth looks quite different. Add into this mountain-building and erosion wearing down the mountains and you get radically different geographies for the planet.

So what did the Earth look like in the past? There are two excellent sources providing maps of the planet through time. The first is the PALEOMAP Project, by Dr. Christopher Scotese. On this website, you will find maps ranging from 650 million years ago to the modern day and even into the future. There are 3D animated globes and interactive maps. He includes a methods section for how the maps wer put together and a list of references and publications. There is also a climate history section providing brief descriptions of the climate at various points in time. For teachers, there are several educational resources available, some of which are free, but others are available for a fee. There is even an app for the iPhone/iPad. It is not available yet for either android or Windows, but that has been admirably taken care of by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute with their Earthviewer app and they have done a wonderful job. the app is fully interactive, allowing easy scrolling through time and full rotation of the globe. You can also track atmospheric oxygen and carbon dioxide, day length, important fossils, biological and geological events, and major meteor impacts. The app even provides a bibliography of their source material. In addition to the maps from Dr. Scotese, the app extends the timeline back to 4.5 billion years (although this extension is obviously not nearly as detailed as the Scotese maps due to the greatly extended time and the greatly decreased amount of available data). All in all, a great app, also reviewed by the NSTA.

So what did the Earth look like in the past? There are two excellent sources providing maps of the planet through time. The first is the PALEOMAP Project, by Dr. Christopher Scotese. On this website, you will find maps ranging from 650 million years ago to the modern day and even into the future. There are 3D animated globes and interactive maps. He includes a methods section for how the maps wer put together and a list of references and publications. There is also a climate history section providing brief descriptions of the climate at various points in time. For teachers, there are several educational resources available, some of which are free, but others are available for a fee. There is even an app for the iPhone/iPad. It is not available yet for either android or Windows, but that has been admirably taken care of by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute with their Earthviewer app and they have done a wonderful job. the app is fully interactive, allowing easy scrolling through time and full rotation of the globe. You can also track atmospheric oxygen and carbon dioxide, day length, important fossils, biological and geological events, and major meteor impacts. The app even provides a bibliography of their source material. In addition to the maps from Dr. Scotese, the app extends the timeline back to 4.5 billion years (although this extension is obviously not nearly as detailed as the Scotese maps due to the greatly extended time and the greatly decreased amount of available data). All in all, a great app, also reviewed by the NSTA.

The second site that will be of interest is the Library of Paleogeography run by Dr. Ron Blakely. These maps cover approximately the same time frame as those provided by Dr. Scotese and are not animated. However, Dr. Blakely provides maps in different projections and provides regional coverage beyond that of global maps. So if you are specifically interested in paleogeographic maps of North America and Europe, this is an excellent resource.

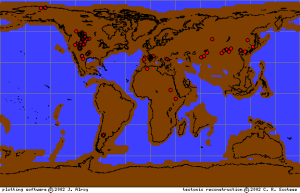

A third site also provides paleogeographic maps which are very useful. In this case, the maps are secondary to the main purpose of mapping fossil locations. The Paleobiology Database contains records of fossil locations that have been published in the primary literature. One can perform a search by organism or group, country, rock unit or type, time interval, paleoenvironment, or publication. The results from the search are mapped onto global maps based on the PALEMAP Project.

All of these sources are available to the public and are used by professional researchers. Therefore, one can safely assume they represent accurate assessments of current, generally accepted thoughts on our Earth through time. You may notice that maps from Scotese and Blakely may not completely agree on all aspects. This is because it is very hard to piece together all the evidence and trace the movements of the continents backwards through time. Often, the data is incomplete and they have to make judgment calls based on the available evidence. Not everyone makes the same choices. This is true even for maps of current geography and is even more so for paleogeography. As we get more data and better techniques, those disagreements become fewer and fewer, but there is still much work to be done, so these maps can and will most likely be refined in the future to reflect new research.

Dig up Digging for Bird-Dinosaurs

Digging for Bird-Dinosaurs: An Expedition to Madagascar

By Dr. Nic Bishop

Publication date 2000. 48 pg. Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN: 0-395-96056-8.

Nic Bishop has combined his avid love of photography and his doctorate in biology into a prize-winning series of books for children. His books include a series on specific groups of animals, such as snakes, lizards, marsupials, spiders, butterflies, as well as a “scientist in the field” series. It is the latter series I am discussing today. There are plenty of books available discussing the different animals, although few with the quality of photography and biological expertise Bishop brings to his work, but there are precious few that discuss the work of the scientist in bringing that knowledge to light as the discoveries are being made, which is what particularly interests me here.

Digging for Bird-Dinosaurs was published in 2000, so it is not current, but is still topical and relevant and should stay so for some time. The only issues with the age of the book are new details that have been discovered, which further confirm the hypotheses presented in the book. When the book was written, most scientists had been convinced that birds evolve from dinosaurs for many reasons which are mentioned in the book. Since the book has been published, many new feathered dinosaurs have been found which clearly show the relationships in further detail. But the book is not really about the relationships between birds and non-avian dinosaurs, although it discusses them quite well, it is about the experience of the people on an expedition to Madagascar in 1998, what it is like being in the field and the study of some of the fossils that were discovered. If you want to know what it is like to go to another country and dig for dinosaurs, this book will be of interest and should make interesting reading for kids in elementary or middle school.

The expedition was led by Dr. David Krause, a professor at Stony Brook University in New York who has been running paleontological expeditions to Madagascar since the early 1990s and is still doing so, although the book is focused on his colleague, Dr. Cathy Forster, also of Stony Brook (at the time, but now an Associate Professor at George Washington University). She, like Krause, is a noted paleontologist and is likely the focus of the book because of the relative paucity of women in the field sciences. These days, if one goes to a meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, women are well represented, but in the 1990s, most of these women were still students looking to the few women like Dr. Forster who were forging careers.

The book follows their experiences in the field and the discovery of a particularly interesting bird-like creature they eventually name Rahonavis. The book continues with the team bringing the fossils back, preparing them out of the rock and studying them, coming to the conclusion that the animal was the closest known bird to Archaeopteryx, which is generally considered the earliest known bird. It is so close in fact, that many scientists today consider it actually closer in lineage to the dinosaurs known as dromeosaurs, which include animals like Velociraptor, than it is to birds. This placement is a great demonstration that birds really did evolve from dinosaurs. It is so hard to tell the difference between “dinosaur” and “bird” in the earliest bird-like forms because they are not distinct, separate groups. Birds are merely a subset, a type of dinosaur, in much the same way that mice are rodents, which are also mammals, which are also amniotes, which are also vertebrates, etc. Therefore, whether or not Rohanavis falls out before or after Archaeopteryx in the lineage is a mere detail, changing nothing of the story. It makes as much difference to the evolution of birds as it does which of a set of twins was born first or second, a matter of inconsequential minutes in evolutionary time.

One of the fascinating parts of the book is when Dr. Krause and Dr. Forster discuss the local people helping them. The villagers are very poor, with no access to healthcare or schools. Dr. Krause was concerned enough that he founded the nonprofit Madagascar Ankizy Fund, which supplies needed healthcare to the area, as well as building schools and providing teachers. Dr. Krause and Dr. Forster came to Madagascar to hunt for fossils. But while they have found a great many spectacular finds, perhaps their greatest accomplishment is in the humanitarian work on behalf of the people who live there.

Time Enough to Evolve

Time. My day job has kept me extraordinarily busy and away from paleoaerie for a while, thus the lack of new posts here recently, so I thought now would be a good time to discuss temporal issues. Fortunately, things have calmed down a bit and I can get back to working on evolving the website. Speaking of which, it is time I got started.

Time is a subject about which much has been written, especially about our perceptions of time. One of the difficulties some people have with evolution is they don’t see how small changes in a population could lead to the diversity of life we see. They read about small changes in bacteria or they hear about how the average height and longevity of people have changed in the past few decades. They understand that a wide variety of dogs have been created through artificial breeding. But, the dog is still a dog, the bacterium is still a bacterium, people have not changed in their personal experience.

Unfortunately, they do not see how their personal experience misleads them. To them, the world is essentially unchanging. While human culture may change, the mountains do not move and species do not change. It is a common human tendency to assume that whatever is now has been and will always be. However, while we may think of hundreds of years as ancient history and thousands of years as vast swaths of time, they are a tiny speck of how long evolution has been altering life on this planet.

So how does one get people to comprehend the incomprehensibly vast time frames we are talking about? People have tried several ways. One could always simply show them the geologic time scale.

This is the standard geologic time scale used by professionals the world over, put out by the Geological Society of America. But to most people, this doesn’t really help. It is words and numbers and humans are just not that good at really getting a gut level understanding of figures like this. So many people have come up with a variety of metaphors. A common metaphor is compressing the age of the universe into a single year, a la the Cosmic Calendar, as popularized by Carl Sagan and expanded upon nicely by Arif Babul at the University of Victoria.

The idea of condensing all of time into a calendar can be re-envisioned as a clock. If we extend the circular motif to three dimensions, we find another popular image in that of a great spiral of life.

The idea of condensing all of time into a calendar can be re-envisioned as a clock. If we extend the circular motif to three dimensions, we find another popular image in that of a great spiral of life.

We could also think of time as distance. If, for instance, we decided to get in our car at the Jacksonville, FL airport and drive west and we thought of each mile being 1,000,000 years, we would have to drive to Fairbanks, AL to reach the whole age of the earth. All of human history would be passed by in less than two standard car lengths. An hour into your drive you would pass the asteroid marking the end of the Cretaceous Period and the demise of the non-avian dinosaurs. You would barely be into Tennessee before you passed the Cambrian Explosion over 500,000,000 years ago. By the time you got back to the origins of life, you would be entering the Yukon territories in Canada.

We could also think of time as distance. If, for instance, we decided to get in our car at the Jacksonville, FL airport and drive west and we thought of each mile being 1,000,000 years, we would have to drive to Fairbanks, AL to reach the whole age of the earth. All of human history would be passed by in less than two standard car lengths. An hour into your drive you would pass the asteroid marking the end of the Cretaceous Period and the demise of the non-avian dinosaurs. You would barely be into Tennessee before you passed the Cambrian Explosion over 500,000,000 years ago. By the time you got back to the origins of life, you would be entering the Yukon territories in Canada.

But these are all static images. Perhaps you would prefer a more interactive approach, such as this interactive timeline or perhaps this one.

But these are all static images. Perhaps you would prefer a more interactive approach, such as this interactive timeline or perhaps this one.

Perhaps you would prefer an interactive in which time was expressed in terms of size.

These are just a few of the ways that time spans can be visualized. Are you looking for something you can bring into a classroom that the students can touch and experiment with? Try having them build a timeline of their own. What is your favorite? Do you have other ideas?

These are just a few of the ways that time spans can be visualized. Are you looking for something you can bring into a classroom that the students can touch and experiment with? Try having them build a timeline of their own. What is your favorite? Do you have other ideas?

Dinosaur Odyssey: a Journey You Should Take.

Dinosaur Odyssey: Fossil Threads in the Web of Life

By Scott D. Sampson

Publication date 2009 (hardback) 2011 (paperback). 332 pg. University of California Press. ISBN: 978-0-520-24163-3.

Suitable for junior high students and up.

Author: Dr. Sampson is best known these days as Dr. Scott the Paleontologist, from Dinosaur Train on PBS KIDS (a children’s show I can recommend). But he doesn’t just play one on TV, he is a real-life paleontologist, and a well-respected one at that, best known for his work on late Cretaceous dinosaurs in Madagascar and the Grand Staircase-Escalante national Monument. He is Chief Curator at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science. He has a blog called Whirlpool of Life and can be found on Facebook. Dr. Sampson has had a longstanding interest in public science education, particularly about connecting children with nature. That interest is clearly evident in Dinosaur Odyssey.

Author: Dr. Sampson is best known these days as Dr. Scott the Paleontologist, from Dinosaur Train on PBS KIDS (a children’s show I can recommend). But he doesn’t just play one on TV, he is a real-life paleontologist, and a well-respected one at that, best known for his work on late Cretaceous dinosaurs in Madagascar and the Grand Staircase-Escalante national Monument. He is Chief Curator at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science. He has a blog called Whirlpool of Life and can be found on Facebook. Dr. Sampson has had a longstanding interest in public science education, particularly about connecting children with nature. That interest is clearly evident in Dinosaur Odyssey.

This book has been out a few years, but its main message is more deeply relevant now than ever before. This book is not really about dinosaurs. It is about the interconnectedness of all things. Dinosaurs are simply a fascinating hook for discussing ideas about evolution and ecology. If you are looking for a book that just talks about dinosaurs, look elsewhere. But if you want a book that puts dinosaurs in context as part of a complete and ever-changing ecosystem, if you want to learn about the Mesozoic world as a stage upon which dinosaurs are only a part, however awe-inspiring and prominent, of a much larger web of life, this book is for you. In Dr. Sampson’s hands, dinosaurs are not skeletons of bizarre creatures, they are living organisms interacting with others, changing and being changed by their environment. In a similar vein, our ideas about them are neither set in stone nor idle speculation, they are dynamic and changing, based on new discoveries and scientific understanding, circling ever closer towards a deeper understanding.

The book is written for someone with decent reading ability, but not a dinosaur aficionado. No real prior scientific knowledge is required, simply a desire to learn about the natural world. For those who want more, or find some of the terminology daunting, there is a wealth of notes and references at the end, along with a substantial glossary. The book begins with a short history of the scientific study of life and Sampson’s personal experiences searching for dinosaurs in Madagascar, which led to some of his thinking for the book as an introduction to what follows. Throughout the book, he uses his personal experiences to enrich the scientific discussions, making it a personal story, not just an academic one. Chapter two is an ambitious glimpse at the history of the universe until the dinosaurs appear, along with a short discussion of the geological principles forming the foundations of our understanding of geologic time. Chapter three introduces the dinosaurs, defining what is meant when a scientist talks about dinosaurs and the different groups of dinosaurs. Along the way, he discusses what species are, how they are named, and how we figure out relationships, although not in detail, just enough for a non-science person to understand the broad concepts. Chapter four discusses the physical world of the Mesozoic in terms of plate tectonics and how the movement of the continents shaped the world and thus the evolutionary history of dinosaurs. He even discusses the role of the atmosphere and oceans in climate. Chapter five builds the basics of ecosystems and nutrient flow, chapter six provides a background in evolutionary theory, chapter seven discusses how dinosaurian herbivores adapted to changing plant communities and how the dinosaur and plant communities may have co-evolved, each influencing the other. Chapter eight adds predators to the mix and chapter nine finishes the ecological chain with decomposers. Chapters ten and eleven discuss sexual selection and metabolism in dinosaurs.

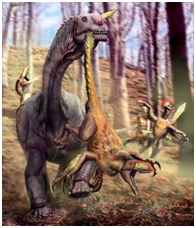

Michael Skrepnick contributed several paintings for the book, such as this one of Daspletosaurus attacking an Einiosaurus herd.

The chapters to this point built up how dinosaurs fit into the ecosystem and the workings of evolutionary theory. The next three chapters then take that information and discuss the dinosaurs rise to prominence in the Triassic, development of dinosaur ecosystems in the Jurassic, and their ultimate development through the Cretaceous period. Chapter fifteen, as might be expected, discusses the extinction ending the Mesozoic Era and the dominance of dinosaurs as major players on the world stage.

One might think the book would end at this point. But Sampson has one final chapter to go, which is probably the most important message in the book. He finishes the book by discussing why dinosaurs are important today. We are facing an extinction event equal to the end of the Cretaceous in terms of biodiversity loss, yet few people seem to notice just how comparatively depauperate our global ecosystems are becoming. Because dinosaurs draw peoples’ attention, they are the perfect tool to discuss evolutionary and ecological issues. In this chapter, Sampson discusses how to use dinosaurs to reach people and teach them about our own ecosystems, how we are affecting it and the problems we are facing. In this way, looking at our past through a dinosaurian lens can help us find our way forward.

In the final analysis, this book is a must-read for anyone interested in the natural world and how it works, especially if they love dinosaurs.

Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages.

By Dr. Thomas Holtz, Jr. Illustrated by Luis V. Rey.

Publication date 2007. 427 pg. Random House. ISBN: 978-0-375-82419-7.

Author: Dr. Holtz, self-proclaimed “King of the Dino Geeks,” or as I like to call him Dr. Tyrannosaur, is a well-known and respected paleontologist who’s understanding of all things tyrannosaur is unparalled. As a senior lecturer at the University of Maryland and the Faculty Director of the Science & Global Change Program for the College Park Scholars, he has extensive teaching experience. I have had the pleasure of attending several of his talks at meetings of the Society for Vertebrate Paleontology and he has always been informative and interesting and his students have always been very positive about him.

Illustrator: Luis Rey is an accomplished and respected artist, known especially for his paleo art. He has won the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Lazendorf Award, given to outstanding artists and his artwork can be seen in several museums, books, and other outlets. He is known for very colorful dinosaurs with close attention to anatomical detail. He makes huge efforts to bring dinosaurs to life as actual, living creatures with as much accuracy as possible. A few have criticized his artwork for being too fanciful, in that he draws wattles and other structures on dinosaurs for which we have no hard evidence. But these structures are extremely difficult to preserve in fossils and their living relatives do have them. Matt Wedel, a noted dinosaur researcher in his own right (although he studies sauropods, not theropods like Dr. Holtz) has said, “If you go bold, you won’t be right; whatever you dream up is not going to be the same as whatever outlandish structure the animal actually had. On the other hand, if you don’t go bold, you’ll still be wrong, and now you’ll be boring, too.” Luis Rey has never been called boring.

Illustrator: Luis Rey is an accomplished and respected artist, known especially for his paleo art. He has won the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Lazendorf Award, given to outstanding artists and his artwork can be seen in several museums, books, and other outlets. He is known for very colorful dinosaurs with close attention to anatomical detail. He makes huge efforts to bring dinosaurs to life as actual, living creatures with as much accuracy as possible. A few have criticized his artwork for being too fanciful, in that he draws wattles and other structures on dinosaurs for which we have no hard evidence. But these structures are extremely difficult to preserve in fossils and their living relatives do have them. Matt Wedel, a noted dinosaur researcher in his own right (although he studies sauropods, not theropods like Dr. Holtz) has said, “If you go bold, you won’t be right; whatever you dream up is not going to be the same as whatever outlandish structure the animal actually had. On the other hand, if you don’t go bold, you’ll still be wrong, and now you’ll be boring, too.” Luis Rey has never been called boring.

I decided to start off my reviews with this book, even though it has been out since 2007, because I think every school should have it. There are good reasons it won “Outstanding Science Trade Books for Students K to 12: 2008 by the National Science Teachers Association. It is called an encyclopedia and it does have chapters describing all the various dinosaur groups, but it is so much more. It is not a small book and here is my only real criticism of the book. Despite its title, it is not quite a book for all ages (School Library Journal rated it Grade 5 and up and it would take an exceptional 5th grader to read it). If you are looking for a book to read to little kids, look somewhere else. It is called an encyclopedia for a reason. Nevertheless, with that caveat in mind, if you are looking for a book to give your dinosaur-obsessed kid who can read well, this book is for you. It is not just for kids though. Adult dinosaur enthusiasts will like it too.

What I like best about this book is that it does not simply focus on the dinosaurs. There are plenty of books that will give you an A-Z description of dinosaurs. Holtz gives the reader a feel for what paleontology is and how it works. The goal of this book is to explain why we think what we do about them, how we know what we know. He starts off the book discussing how science, particularly as it applies to paleontology. He then has a chapter on the field’s history, followed by three chapters of geology and geologic time to put everything into perspective. Chapters 5-9 discuss how paleontologists find fossils and attempt to reconstruct what they looked like and how they are related to each other. It is not until chapter 10 that he even starts talking about dinosaurs themselves and that chapter simply explains how they are related to other vertebrates. Chapters 11-35 are the meat of the book that everyone would expect. This is where he discusses the amazing diversity of dinosaurs. The last five chapters discuss dinosaur behavior and metabolism and how we approach topics like this that are not so easy to see in the fossils. The last three chapters then put the dinosaurs in context of time and ecology. Contrary to popular opinion, dinosaurs did not all live at the same time. They spanned a vast length of time and these chapters give the reader some sense of what the earth was like during the major time periods, who lived when and what other animals they lived with. The last chapter ends predictably with a discussion of extinction, but rather than just say the asteroid killed them all off, Holtz discusses some of the complications of that hypothesis, finishing off with how life continued after the asteroid impact (including the dinosaurs, who were only mostly dead, not completely dead, a few made it through and thrived as birds). At the end of the book is a series of tables listing all the dinosaurs, including where and when they lived and their estimated size and weight.

What I like best about this book is that it does not simply focus on the dinosaurs. There are plenty of books that will give you an A-Z description of dinosaurs. Holtz gives the reader a feel for what paleontology is and how it works. The goal of this book is to explain why we think what we do about them, how we know what we know. He starts off the book discussing how science, particularly as it applies to paleontology. He then has a chapter on the field’s history, followed by three chapters of geology and geologic time to put everything into perspective. Chapters 5-9 discuss how paleontologists find fossils and attempt to reconstruct what they looked like and how they are related to each other. It is not until chapter 10 that he even starts talking about dinosaurs themselves and that chapter simply explains how they are related to other vertebrates. Chapters 11-35 are the meat of the book that everyone would expect. This is where he discusses the amazing diversity of dinosaurs. The last five chapters discuss dinosaur behavior and metabolism and how we approach topics like this that are not so easy to see in the fossils. The last three chapters then put the dinosaurs in context of time and ecology. Contrary to popular opinion, dinosaurs did not all live at the same time. They spanned a vast length of time and these chapters give the reader some sense of what the earth was like during the major time periods, who lived when and what other animals they lived with. The last chapter ends predictably with a discussion of extinction, but rather than just say the asteroid killed them all off, Holtz discusses some of the complications of that hypothesis, finishing off with how life continued after the asteroid impact (including the dinosaurs, who were only mostly dead, not completely dead, a few made it through and thrived as birds). At the end of the book is a series of tables listing all the dinosaurs, including where and when they lived and their estimated size and weight.

Holtz doesn’t go it alone either. Scattered throughout the chapters are inserts from other researchers (such as Dr. Kristi Curry Rogers shown here) explaining various topics related to their own research, so the reader gets the perspective of many paleontologists, not just the author’s.

Holtz doesn’t go it alone either. Scattered throughout the chapters are inserts from other researchers (such as Dr. Kristi Curry Rogers shown here) explaining various topics related to their own research, so the reader gets the perspective of many paleontologists, not just the author’s.

A serious bonus for this book is that Dr. Holtz has attempted to keep the book as current as possible by posting online corrections necessitated by new research, which you can find here.

As a final word, the book is superbly illustrated with numerous drawings, both in monotone and vivid color, by Luis Rey. There are no images of actual fossils, which some have criticized the book for, but my personal feeling is that the book was not designed to be a textbook for dinosaurs. It was designed to show the dinosaurs as living animals, not simply as their bones. There are plenty of other places one can find that. This book is for a view of what they were like alive and most importantly, why we think they were like that shown here and how we study them.

As a final word, the book is superbly illustrated with numerous drawings, both in monotone and vivid color, by Luis Rey. There are no images of actual fossils, which some have criticized the book for, but my personal feeling is that the book was not designed to be a textbook for dinosaurs. It was designed to show the dinosaurs as living animals, not simply as their bones. There are plenty of other places one can find that. This book is for a view of what they were like alive and most importantly, why we think they were like that shown here and how we study them.

For other reviews of this book, try here, here, here, and here, among others. All illustrations above can be found within the book, as well as the linked sites for Luis Rey and Dr. Rogers.