Home » Uncategorized (Page 5)

Category Archives: Uncategorized

6 Ways to Completely FAIL at Scientific Thinking, Part 2

Last post, I covered two of the six most common mistakes people make in their thinking. Today I will cover the next two: appreciating the role of chance and misperceiving the world around us. Both of these are huge topics, so as Inigo Montoya said, “Let me ‘splain. No, there is too much, let me sum up.”

Last post, I covered two of the six most common mistakes people make in their thinking. Today I will cover the next two: appreciating the role of chance and misperceiving the world around us. Both of these are huge topics, so as Inigo Montoya said, “Let me ‘splain. No, there is too much, let me sum up.”  3. We rarely appreciate the role of chance and coincidence in shaping events. Last time we discussed just how much people hate and misuse statistics. Another way our inbred antipathy for statistics comes into play is not understanding the role of chance. People seem to need to have a cause for everything. If something goes wrong, something must be to blame. We hate to admit that anything is left to chance (which, considering that quantum physics makes everything in the universe a probability, make explain why people don’t understand it). As even Einstein said, “God doesn’t play dice with the world.” However, given enough time or occurrences, even rare events occur. I once had a geology professor who told me that given enough time, events that are almost impossible become likely and rare events become commonplace. This is quite true, over enough time and with enough attempts, even the rarest events will happen. Sometime in your life, you are almost certainly going to see something that is incredibly, inconceivably rare. People talk about 1 in a million chances being so rare as to be inconceivable and not worth thinking about, but that chance happens to over 7000 people worldwide, it will happen to eight in New York alone. Occasionally, you will be among that 7000.

3. We rarely appreciate the role of chance and coincidence in shaping events. Last time we discussed just how much people hate and misuse statistics. Another way our inbred antipathy for statistics comes into play is not understanding the role of chance. People seem to need to have a cause for everything. If something goes wrong, something must be to blame. We hate to admit that anything is left to chance (which, considering that quantum physics makes everything in the universe a probability, make explain why people don’t understand it). As even Einstein said, “God doesn’t play dice with the world.” However, given enough time or occurrences, even rare events occur. I once had a geology professor who told me that given enough time, events that are almost impossible become likely and rare events become commonplace. This is quite true, over enough time and with enough attempts, even the rarest events will happen. Sometime in your life, you are almost certainly going to see something that is incredibly, inconceivably rare. People talk about 1 in a million chances being so rare as to be inconceivable and not worth thinking about, but that chance happens to over 7000 people worldwide, it will happen to eight in New York alone. Occasionally, you will be among that 7000.

Have you ever called someone only to find out they were trying to call you at the same time? I have done that with my wife. Many people invoke something mystical or a psychic connection that made us call at exactly the right time because surely, what are the chances of two people just happening to call each other at the exact same time? However, I talk to my wife on the phone far more often than I talk to anyone else. Considering the number of times that my wife and I try to contact each other, it is almost inevitable that sooner or later, we would try at the same time. There are those that seem to be consistently lucky or unlucky. If it were really just random chance, then it should all even out and everyone should be equally lucky (or not), right? Here again, with enough people, some people will just randomly be consistently luckier than others, no supernatural force required. There will always be outliers that don’t follow the typical pattern just through random chance.

You can see this same type of mistake when people incorrectly tie independent chances together. When flipping a coin, a string of 20 heads will do nothing to change the chance that the next flip will be heads or tails. This sort of mistake is often seen in gamblers and people playing sports in their belief of winning and losing streaks, in which the results of a series of chance occurrences is thought to affect the odds of future events. So how do we avoid this mistake? Never put much stock in one occurrence. Look at the accumulated data and weigh occurrences accordingly.

Probably one of the biggest fallacies people make in this regard is mistaking correlation for causation. Just because two events occur at the same time does not necessarily mean they are connected. Wearing a specific shirt when you win a game does not make it lucky. It will not influence the outcome of any other game except in how it affects your thinking. I can think of no better example of this than the Hemline Theory, which states that women’s skirt lengths are tied to the stock market. Sadly, despite such an absurd premise, it is still commonly believed and one can still find articles debating the merits of the hypothesis. Needless to say, even if they do tend to cycle together, it would be foolish to say that the stock market is controlled by what skirts women are wearing. What might be plausible is that both are influenced by some common factor. Thus, any study which claims to have found a correlation between two events or patterns has only taken the first step. Once a correlation has been found, it is then necessary to demonstrate how one affects the other. Often, it is found that there is no direct connection, but they may both be influenced by an altogether different factor. Check out the site Spurious Correlations to see almost 30,000 graphs showing correlations between totally random occurrences, such as the graph showing that increased Iphone sales are correlated with a drop in rainfall in Mexico, or that US STEM spending is associated with the suicide rate. How to avoid this problem? Look for multiple lines of evidence and a causal mechanism that explains how one could affect the other. Without that mechanism, you can only say that two things have something in common, you should avoid saying one thing caused the other until you can point to a direct connection.

Spurious Correlations. http://www.tylervigen.com

4. We sometimes misperceive the world around us. Many people make the assumption that that their eyes work like cameras, recording faithfully everything in their field of view and the brain accurately records everything that goes into it. Unfortunately, this is not true. Our senses are imperfect. They neither record all the information, nor does the brain provide a complete image of what is around you. Simply put, you cannot trust your senses. Magicians count on this. One of the best I have seen is Derren Brown, who uses a mixture of psychology and good old-fashioned stage magic to perform his tricks. Visual and aural illusions abound. Take our eyes for example. Unlike a video camera that records the whole scene within the confines of its lens at the same time. We put together images from fragments. We rapidly move our eyes all around our field of view in what are called saccades, focusing on one small bit, then another. The light enters the eye and is picked up by the retina, with rods detecting intensity of light and cones detecting color. Signals from these receptors do not enter the brain as a picture. They are filtered through specialized cells, some of which detect boundaries to sharpen focus, some detect movement, etc. All of these separate signals gets sent to the brain which puts together a patchwork image, an image with a lot of gaps. We don’t usually see these gaps because our brains fill them in with what past experience tells it to expect. This is a really important point. Past experience affects what we see. Our hearing works this way as well.

The fact that past experience affects what we see plays out in various ways. We overlook things that change between eye movements. We fill in the gaps with what we expect to see. Thus, how we view the world is in part dependent on what we expect to see and our expectations are based on our experiences. People with different experiences may view the same thing very differently. This happens so much that when we see something that does not fit our expectations, our brains can even go the point of overwriting the visual input with our prior expectations. And it gets worse. If we focus on something, this tendency to be blinded to other things increases. Most people have heard of ignoring the elephant in the room. A couple of researchers at Harvard did what they call the invisible gorilla experiment. People were asked to observe a group of people wearing shirts that were two different colors. They were told to count the number of times a ball was passed between members of the group wearing the same color shirt. Most people could successfully do this. However, many people missed the man in a gorilla suit who walked into the middle of the group, paused to look at them, and then walked off.

How could someone miss such an obvious thing? They were focused on the ball and missed the bigger picture. This problem is called selective attention or “inattentional blindness.”. This experiment has been done with hearing, in which the participants were to listen to only one of two conversations going on at the same time. This time, part way through, someone started saying, “I’m a gorilla,” multiple times. If just told to listen to the recording, everyone could hear it easily. But if told to listen carefully to only one conversation, most people never heard the gorilla. There are many, many examples like this of selective attention. This is exactly why eyewitness accounts in trials are not worth very much. You might hope it stopped at this level, but it doesn’t. Even if we accurately see what is there, our prejudices will affect our interpretation. Different colors affect our moods and perceptions. Religious or political beliefs affect our perceptions to the point we will literally see things differently, even our views of sports games. Space allows only a cursory mention here, but it is easy to find many, many studies, books, and shows that demonstrate just how unreliable our personal observations are. So how do we avoid this? To begin with, we recognize that our perceptions are fallible. Thus, the more independent observations we can make and the more people that observe it, the more likely it is to be valid. Take recordings that can be viewed and listened to at different times. Try this out for yourself. Watch a movie with other people. Have someone prepare a list of questions in advance about a particular scene. After everyone has viewed it, have everyone answer the questions on their own and then compare them. Most likely, you will find some things people answered differently, other things some people did not see at all. Or just listen to the responses from political leaders after any speech by any President. The best way to get around this problem is through multiple, independent observations. Never trust just one observation and always question the biases of the observer.

Next post we will wrap up this series with the last two common mistakes. Stay tuned.

Best Introduction to Evolution Textbook

The Tangled Bank: An Introduction to Evolution

Publication date (2nd ed.): 2013 according to publisher (my copy says 2014), 452 pg.

Roberts and Company Publishers. ISBN: 978-1-936221-44-8.

Author: Carl Zimmer is one of the best science writers in the business. You can keep up with him on his blog, which is part of the National Geographic “science salon” called Phenomena, a collection blogs by Carl Zimmer, Brian Switek, Ed Yong, Virginia Hughes, and Nadia Drake, all of whom are experienced science writers with a talent for accuracy and clarity. They cover everything from dinosaurs to DNA to dark matter and are the first place I go to in the morning for interesting science news. If it sounds like I am selling them, I am in order to convince you that a book by Carl Zimmer is both more accurate than the current textbook you are using and better written. Zimmer and the others are not just authorial guns for hire, they care about science communication and they do it well. My first introduction to Carl Zimmer was a book called “Parasite Rex“. You probably are thinking that a book about parasites would not be the most interesting of books, but you would be wrong. Read it and it will open up a whole new (albiet disturbing) world for you.

The name of the book is derived from the opening line of the last paragraph in The Origin of Species, by Charles Darwin, a fitting name for a book introducing evolutionary topics. While I have a few complaints, none are major and I highly recommend the book. My chief complaints are that I always want more, but there is only so much one can put into a book, especially an introductory text.

The book is filled with high quality pictures and graphs that break up the text, but whereas many books have flashy graphics that serve little purpose other than to distract from the text, all the figures in the book clearly relate to the topic at hand without excessively cluttering up the book. They also provide data that get the reader to go beyond the “because I told you” format so many books use and actually look at some of the data supporting the scientific concepts (and serve as a great way to integrate math, geography, and art standards into the science). Each chapter also have a list of resources for further reading and an extensive bibliography, so anyone can check the data presented in the primary and peer-reviewed literature for themselves.

One thing that might make some teachers and students a little annoyed is that important terms are not in bold font, nor does it have problem sets. However, it explains all the terms as they come up, it does not require flipping to the end of the book for every new term, although there is also a glossary for those that need it. The book is designed to be read, not just skimmed through while one picks out the bold words, like so often happens. However, there is also a study guide for the book written by Dr. Alison Perkins, which includes all the learning objectives, questions, activities, and pedagogical suggestions that teachers are looking for.

The book begins with a detailed discussion of whale evolution as an example to introduce several general concepts of evolution and various ways in which evolution may be studied. It covers fossils, placing them into phylogenetic and geologic context, DNA studies, embryology, and ecology from their earliest beginnings to today. Zimmer doesn’t go into the disputes that arose about whale origins, instead just focusing on what has become the consensual understanding, which I find a bit disappointing, but perfectly understandable for the context of this book and especially this introductory chapter. Nevertheless, I like presenting disputes because it shows the dynamic nature of science as an exploration, not just a book of facts. He presents the exploration through a discussion of the fossils being discovered and how they were interpreted, he just cleans up the historical path and makes it neater than it really was.

Chapter 2 brings a history of evolutionary thought, starting in the 1600s and the development of evolutionary concepts before Darwin. Zimmer correctly explains that Darwin was not the first to conclude that organisms evolved, but he did provide a plausible mechanism for how it happened. He then continues with a discussion of the changes and additions to evolutionary theory in the decades since Darwin. He tackles the important misconceptions of evolution, including the common misunderstanding of what a scientific theory really means, which form the basis of most people’s arguments against evolution.

Chapter 3 presents geological data, including how radioactive decay is used to date rocks and biomarkers to detect traces of life within rocks. He tells us how fossils tell us about the past, followed by a brief overview of the major transitions in life from the dawn of life to today.

One of the many phylogenetic trees in the book showing the evolution of, in this case, birds from dinosaurs.

Chapter 4 is probably one of the most important chapters that is left out of many introductory biology texts. Zimmer tells us what phylogeny is and how to read a phylogenetic tree to understand evolutionary relationships. It is particularly disturbing so many books skip this step because it is vital to understanding much of what comes after. Misunderstandings here reverberate throughout one’s ability to understand evolutionary theory, yet reading phylogenetic trees is not as intuitive as most teachers think. He talks about homology and how that affects our understanding of evolution. After he introduces the concepts, he demonstrates the concepts through a series of phylogenetic trees, such as early mammals, dinosaurs, and hominids.

Chapter 5 talks about DNA and how variation is introduced. Zimmer does a great job of discussing the various types of mutations and showing the typical view of point mutations is but the smallest way of introducing variation. His discussion of the role of sexual selection in creating diversity is short, although his description of Mendel’s experiment with peas helps somewhat. He also gives short shrift to lateral (aka horizontal) gene transfer, in which genes are transferred not through descendants but sometimes through completely unrelated organisms by, for instance, viruses. Zimmer also completely ignores endosymbiosis, which helped create mitochondria and chloroplasts, and hybridization, which makes this chapter not as satisfying for me.

Chapter 6 covers the role of genetic drift and selection well, although he leaves out a discussion of gene flow from one population to another. I like that he talks about fitness in terms of more than one gene, showing that what may be good for one gene is not necessarily good for another in terms of fitness, so that evolution is limited by the interplay between genes that each have their own optimal conditions. This would have been a good place to address the misunderstanding of “survival of the fittest,” which is commonly viewed as a tautology (the fittest survive, but how do you determine who is fittest? The ones that survive) but he does not mention it. This is a very common misconception. First, the phrase was never used by Darwin and is incorrectly and second, it is being incorrectly interpreted. It is not the overall fitness of a particular organism that matters, but a measure of how many offspring successfully survive and reproduce. It doesn’t matter evolutionarily if you are the toughest guy on the block if you don’t breed and produce successful offspring.

Chapter 7 discusses molecular phylogenies, figuring out evolutionary relationships from their DNA or protein sequences. One complaint I have here is that he talks about how successful the molecular clock is, how you can tell time using the amount of mutations separating species. In all actuality, the molecular clock has some serious issues, as in, it doesn’t work very well. Fortunately, he does discuss some of the challenges of the molecular clock (genes don’t mutate at the same rate either between each other or within different parts of the same gene, or through time, it requires fossils to calibrate and then tries to claim better results than the fossil data, etc.). The problems with the molecular clock mean that its usefulness and accuracy are limited and requires statistical manipulation of the data to try to take into account the known issues. Unfortunately, the figures lead one to believe the molecular clock actually acts clock-like, reducing the impact of the text describing its problems and the examples in the text downplay the problems. A bonus to this chapter is that he brings back the topic of horizontal gene transfer and shows its importance in a box at the end of the chapter. I might have put this in the last chapter and discussed it more, but it could be that Zimmer thought it might confuse people by introducing too much complexity at once and wanted the readers to develop a bit more understanding before throwing another wrench in the works.

Chapter 8 gives a great discussion of adaptation, taking it from the gene to species evolution. I particularly like his discussions showing how gene duplications and rewiring without the need for further point mutations can make huge differences. This is a really important concept to understand, that variation is more than just the single point mutations most people think about. He ends the chapter with a discussion of the limits of evolution based on physical limits and baggage from previous evolutionary steps, although I would have liked to see a brief mention at least of the constraints imposed by having genes with different optimal conditions that all have to be balanced.

Remember when I said chapter 5 gave short shrift to variation through sexual reproduction? That is because chapter 9 is completely devoted to the topic. Here he goes into several aspects of sexual selection, including trade-offs that may limit evolution in any one particular direction. Trade-offs in this case refer to the fact that improving one thing takes away from another. The genes with different optimal conditions are an example of this. Improve and you hurt another until a balance is achieved.

Chapter 10 defines what a species is (which is nowhere near as easy as it sounds) and how species evolve into other species. Chapter 11 extends that to evolution on a grand scale, showing the development of global biodiversity through time. I would have preferred to see a discussion of the difficulties in determining fossil biodiversity, such as the relationship between the amount of outcrops of a particular time and the number of species known, but there is only so much one can put into a textbook. Inevitably, the chapter discusses the major extinctions of the world, although he only talks about two of them, the Permo-Triassic and the Cretaceous-Paleocene extinctions, probably because they are better known by far than the others. His discussion of the Permian extinction doesn’t mention that the reason the volcanoes at the time put out so much carbon dioxide was that they apparently burned through huge coal deposits, which pumped up the carbon dioxide way beyond what the volcanoes would have done alone, but he gets the gist of the cause of the extinction. He also discusses briefly the debate in why the extinction occurred at the end of the Cretaceous, which is good. The chapter ends with a discussion of the current mass extinction taking place and the causes for it.

Chapter 12 discusses coevolution, both mutualistic and antagonistic. Here Zimmer finally discusses endosymbiosis and the important role it played in evolutionary history. Chapter 13 is an interesting discussion about the evolution of behavior in both plants and animals.

Chapter 14 will of course be the most controversial chapter because it deals with human evolution. Zimmer does a good job with this chapter, although I would have preferred a clearer statement that hominids and apes both evolved from a common ancestor, but where our ancestors became adapted for savanna life, the apes evolved more towards forest life. He talks about the interbreeding that happened between neanderthals and Homo sapiens, as well as with the Denivans, according to the genetic research published recently, which will make a few people uncomfortable, but is the truth nevertheless. The chapter wraps up with a discussion of some evolutionary psychology, which is highly controversial, but the parts he discusses are well supported by experimental evidence.

The last chapter is arguably the most important one in the book. Here Zimmer discusses the role of evolution in medicine, with examples of disease progression, vaccines, antibiotics, and cancer. If, by the time people have worked their way through the book and are still asking themselves why it is important they understand evolution, this chapter is a sledgehammer wake-up call. One cannot finish the book without having a strong understanding of the importance of this concept of evolution and why biologists consider it the central tenet of all biology. As Dobzhansky said, “Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution.”

The ethics of fossil collecting

Today’s Google doodle celebrates the 215th birthday of Mary Anning. She was one of the first people to help usher in the modern age of paleontology as a science and was the prime worker on the Jurassic Coast near Dorset, England, probably the most important fossil site for marine reptiles in the world. The Natural History Museum of London calls her “the greatest fossil hunter ever known..” Among other finds, she is credited for finding the first correctly identified skeleton of an ichthyosaur, the first complete specimens of a plesiosaur, the first pterosaur outside Germany, and identifying coprolites as fossil feces. Until that time, they were called bezoar stones, indigestible masses found within the digestive system. They were rumored to be an almost universal antidote for poisons and were used as such in J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series. The first woman to receive a eulogy at the London Geological Society, an honor given only to distinguished member scientists (she wasn’t even a member because the society did not accept women at the time, they just took her work and published it under their names), Mary Anning was widely sought after by researchers in her time for her expertise.

This brings up an interesting debate. It is hotly debated what role commercial fossil dealers have in paleontology. The current majority consensus as presented by the Society for Vertebrate Paleontology is that they should be stopped because all the fossils they collect are sold, almost always, to private collectors, thereby removing them from scientific study. Fossils that are not in the public trust (like a museum) are not accessible to other scientists to study, so all the knowledge that may be gleamed from their study is lost to the public. They explicitly state this in their bylaws. Section 6, Article 12 states: “The barter, sale or purchase of scientifically significant vertebrate fossils is not condoned, unless it brings them into, or keeps them within, a public trust. Any other trade or commerce in scientifically significant vertebrate fossils is inconsistent with the foregoing, in that it deprives both the public and professionals of important specimens, which are part of our natural heritage.”

They have a point. Few fossils collected by commercial fossil dealers ever get scientifically studied. Who knows how many priceless and important fossils are locked away in someone’s private collection. Museums do not have the resources to compete with private competitors to buy fossils except in the rarest of occasions and even then, it depends on the finances and good will of private individuals willing to donate to the museum for that purpose. The tyrannosaur named Sue sold at auction for $7.6 million to the Field Museum in Chicago, who needed the help of the California State University system, Walt Disney Parks and Resorts, and McDonald’s, along with numerous individual donors to raise the money. Researchers collecting fossils must always be on their guard to protect their dig sites due to the common occurrence of thieves stealing fossils from their dig sites to sell them. Many paleontologists have stories of finding a skeleton at the end of the season and having no time to collect it, only to come back the next season to find someone has collected the sellable parts and not uncommonly have smashed the rest. Even if the fossils find their way to a public institution where they can be studied, most commercial fossil collectors do not take sufficient notes about location and all the details at the site to make the find reliable enough to study well. It is often said that a fossil without provenance data has little more worth than having no fossil at all and for good reason. If you don’t know where a fossil came from, there is little you can say about it and it is impossible to place it in context with other fossils.

On the other hand, commercial fossil collectors say that without them, most of the fossils they collect would have eroded away and been gone completely with no record of them ever having existed at all. There simply aren’t enough paleontologists and money in academia to collect all the fossils they do and they are right. The tyrannosaur Sue is a great example of a dinosaur fossil that may not ever have been found if it were not for commercial fossil dealers. What makes this point important for this essay is that Mary Anning was a commercial fossil dealer. She funded her research and supported herself by selling fossils. Without the income she received from fossil sales, she would never have been able to make the discoveries she did.

Possibly the only known photograph of Mary Anning and she is not even credited in the photo, which is called The Geologists. 1843, Devon. Salt print by William Henry Fox Talbot. Photograph: The National Media Museum, Bradford

So who is right? Maybe they both are. It is undeniable that unscrupulous poachers and fossil dealers steal and destroy priceless fossils which never enter the public and academic consciousness, but it is also undeniable that commercial fossil dealers have contributed greatly to our knowledge of paleontology. The AAPS, Association of Applied Paleontological Sciences, an organization representing commercial fossil dealers, advocates for responsible collecting, having a professional academic work with commercial fossil dealers so any finds can be studied. Their position would indeed help bridge the gap between the academic and the commercial dealer. However, this requires the benevolence of the collectors and many, possibly most, are uninterested in letting academics study their fossils. While the fossils may be able to be studied during the time they are found and prepared (removing the encasing rock and putting the pieces together), most of the study comes after this point. A fossil in private hands can easily become lost and access is at the mercy of the owner. A museum, on the other hand, is required to maintain records of the fossils and provide access to anyone who wants to study them.

So what is to be done? Currently, it is illegal to collect vertebrate fossils on Federal land. The reasoning is that Federal land is owned by everyone. As such, anything on Federal land must be protected for all citizens, making collections for private sale not in the interests of the country as they take fossils out of the public trust and therefore inaccessible to the public. States have their own rules, some make it illegal, others have no specific laws concerning fossil collections. On private land, there are no restrictions. Any fossils found on private property are the property of the land owner and they can do whatever they want.

So what is to be done? Currently, it is illegal to collect vertebrate fossils on Federal land. The reasoning is that Federal land is owned by everyone. As such, anything on Federal land must be protected for all citizens, making collections for private sale not in the interests of the country as they take fossils out of the public trust and therefore inaccessible to the public. States have their own rules, some make it illegal, others have no specific laws concerning fossil collections. On private land, there are no restrictions. Any fossils found on private property are the property of the land owner and they can do whatever they want.

What is the correct answer? That depends on your point of view. Certainly the collective point of view has changed through time. What do you think?

Fossil Friday

It’s Friday, time for the answer to Monday’s mystery fossil. Were you able to identify it?

These fossils are from a fish called Enchodus, the “saber-fanged herring.” Teeth of Enchodus are commonly found in the Cretaceous-aged rocks in southwestern Arkansas, especially near Malvern and Arkadelphia in the Arkadelphia and Marlbrook Marl Formations, up into the Paleocene rocks of the Midway Group a bit farther north. In other places you can even find them in rocks of Eocene age, although you will have much better luck in the Cretaceous rocks. At this time, southern Arkansas was shallow to coastal marine. Go to the Bahamas, imagine Enchodus, mosasaurs, plesiosaurs, and plenty of sharks in the water around the islands and you would have a good picture of the landscape back then. They were abundant at the end of the Mesozoic Era and survived the asteroid impact that rang the death knell for many animals, including the non-avian dinosaurs. But they never regained their prominence as a key member of the marine ecosystem, eventually dying out completely in the Eocene sometime around 40 million years ago (the Eocene lasted from 55 to 34 million years ago).

These fossils are from a fish called Enchodus, the “saber-fanged herring.” Teeth of Enchodus are commonly found in the Cretaceous-aged rocks in southwestern Arkansas, especially near Malvern and Arkadelphia in the Arkadelphia and Marlbrook Marl Formations, up into the Paleocene rocks of the Midway Group a bit farther north. In other places you can even find them in rocks of Eocene age, although you will have much better luck in the Cretaceous rocks. At this time, southern Arkansas was shallow to coastal marine. Go to the Bahamas, imagine Enchodus, mosasaurs, plesiosaurs, and plenty of sharks in the water around the islands and you would have a good picture of the landscape back then. They were abundant at the end of the Mesozoic Era and survived the asteroid impact that rang the death knell for many animals, including the non-avian dinosaurs. But they never regained their prominence as a key member of the marine ecosystem, eventually dying out completely in the Eocene sometime around 40 million years ago (the Eocene lasted from 55 to 34 million years ago).

The fish reached sizes over 1.5 meters, which makes them on the large side, but not really big, considering there were mosasaurs in the same waters that surpassed 10 meters. Still, with fangs longer than 5 cm, they would not have been fun to tangle with. They were clearly effective predators on smaller fish and possibly soft animals like squid. At the same time, fossils have been found showing they were themselves prey for larger predators, such as sharks, the above-mentioned mosasaurs, plesiosaurs, and even flightless seabirds such as Baptornis. Baptornis was a toothed, predatory bird, but as it only reached 1 meter or so, it would have only been able to hunt young Enchodus. So like many of us today, Baptornis was always up for a good fish fry.

Hesperornis, a larger version of Baptornis, and a few Enchodus feeding on some herring-type fish. Picture by Craig Dylke.

Enchodus is often called the “saber-fanged herring,” although it is unrelated to herrings. So what then was it? Herrings are what is known as forage fish, meaning they are mostly prey items of larger fish and other animals. Most of the fish called herrings are in the family Clupeidae in the groups Clupeiformes, which includes such well-known fish as sardines and anchovies. Enchodus, on the other hand, has been placed into the group Salmoniformes, which includes trout, char, and of course, salmon. When one typically thinks of trout and salmon, one doesn’t think of bait fish, they think of the fish that eat the bait fish. Thus, Enchodus would better better described as a fanged salmon (they were a bit large to call them fanged trout).

Mystery Monday

This week’s fossil is a pretty little coiled animal. Can you guess what it is?

The Worst Headline in the World

“Sea Anemones are Half-Plant, Half-Animal, Gene Study Finds.”

Ok, maybe calling it the worst headline in the world is a little hyperbolic, but it is a terrible headline. I have seen this headline over and over again, phrased exactly the same way, indicating that many, many sites do not bother even attempting to write their own versions, but simply cut and paste from other sources. But that is not the problem I have with it. The headline is woefully incorrect, seriously misleading, and damages all the hard work educators have spent trying to get people to understand genetics and how it affects our evolutionary understanding. The people who wrote this headline should really have known better and the people who wrote the articles should certainly have known better. For an example of a well written article that really explains what the research says, yet has this horrid title to it, try here. The information in the article is excellent if one can get past the horribly misleading title. In many cases, the author of the article is not to blame because the headlines are written by completely different people, who don’t necessarily either read nor understand what the article really says. That is a serious problem because many people, if not most, only read the title, or if they read the article, only remember the spin imposed by the title. Thus, titles matter (for more information on the effects of headlines, try here, here, here, here, and here).

The headline and many of the articles imply that a new study on the genetic code of the sea anemone revealed a mixture of animal and plant DNA. The research does not in fact say that. So I will attempt here to explain what it really DID say. To summarize, the genome of the sea anemone is very similar to other animals because it is, you know, an animal. However, there are certain key aspects of its gene regulation that are similar to plants. This is not as bizarre as it might sound though.

To begin with, let’s clarify what the article is referring to. Most of the time, when people talk about genetics, they are referring to the nucleic acid sequences, specifically Deoxyribonucleic Acid, or DNA, that code for genes. This is actually only a small part of the DNA. The rest is taken up with a variety of other things, including a variety of gene regulatory elements, junk DNA (broken genes, viral sequences, etc.), and chromosome structural sequences. The genome, or total genetic sequence, collected into a set of chromosomes, can be thought of as a book. The text includes all the gene sequences, but most of it has been marked out and written over ( what is often referred to collectively as “junk DNA”). The table of contents, page numbers, chapter headings, introductory publishing information, and index would be the regulatory bits; and the spine, cover, pages themselves, and everything holding it all together would be the structural elements. All of these parts are included in the complete DNA sequence, along with various proteins like histones that help package all the DNA.

Pretty much all of this DNA in the sea anemone, according to the study, is very similar to other animals, even vertebrates like us. The genes are similar, the regulatory sequences are similar, pretty much everything is similar. This is interesting because it speaks to the relative closeness of relationships between all animals. The genes used by sea anemones are simply variations of genes found within us. The regulatory sequences are variations of the same sequences we use.

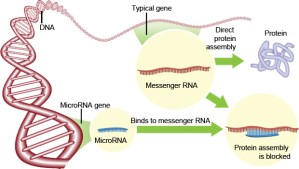

However, not everything is the same. There are small sequences called micro-RNAs. Ribonucleic acid, more commonly just called RNA, is most commonly known as the molecules that help translate DNA gene sequences into working proteins. But that is not all they can do, Unlike DNA, RNA can do more than act as a codex of information. RNA can act as an enzyme at the same time. Enzymes are typically proteins that act on other proteins or on the DNA and RNA themselves. When micro-RNAs act on the DNA and RNA, they regulate expression of the genes, altering how much and what kind of proteins are created. This is where sea anemones differ from other animals. The micro-RNA of sea anemones is more like plants than animals. It had always been supposed that plants and animals evolved their versions of micro-RNAs separately, because they use different sequences and use different molecular pathways. They act differently. For instance, in animals, micro-RNAs bind to multiple proteins and inhibit their functions. Plant micro-RNAs are much more specific and slice up the protein, they don’t just inhibit them. Thus, it may be that sea anemones are telling us that the system developed before plants and animals split off from the ancestral organisms from which both plants and animals evolved. Not only that, but that the original pattern was kept by plants and substantially altered in animals.

The other part of this story that is not made clear is just what relationship sea anemones have with other animals, as well as plants for that matter, which in this case is fairly important. When looking at the early history of eukaryotic (with a nucleus containing DNA), multicellular animals, sea anemones are really, really early. Sea anemones are part of a group called cnidarians. Cnidarians, so named for cells called nematocysts, or stinging cells, also include what are generally called jellyfish, along with coral. On the tree of animal life, you can’t get much more primitive. The only animals thought to have evolved earlier than cnidarians are sponges and ctenophores, commonly known as comb jellies. They are so close to the base of the animal tree of life, one might say if they were lower, they would be only a step away from being fungi. Fungi, according to the genetic research, branched off from the animal lineage shortly after the split between animals and plants, which indicates just how closely related these early forms are.

In addition to being really close to the the plant/animal split, there is one last thing to consider. Sea anemones, like coral, depend on a mutualistic symbiosis with green algae, which, obviously, are plants. The algae collect sunlight to make sugar and oxygen, which gets shared with the sea anemone. The sea anemone in turn provides the algae a secure home, guarded by venomous tentacles. This relationship is similar to the well-known symbiosis with clownfish (remember Finding Nemo?), in which the clownfish gets protected from predators while providing food for the anemone. This is one case in which having messy tenants is actually a good thing.

Now, considering that the anemone relies on algae for its survival, linked as it is metabolically to the algae, and evolutionarily is not that far from being a plant itself, is it any surprise then to find that some of its metabolic regulation uses a system seen in plants? Sea anemones are not half animal/ half plant. They are extremely primitive animals that have their metabolisms linked directly to a plant, unlike the indirect link that other animals have (eating plants or animals that eat plants is a strong, but indirect link, wouldn’t you say?).

Fossil Friday, make it a Productive one

Were you able to solve Monday’s mystery fossil? They aren’t little poop balls, nor are they clams, although they are often mistaken for them.

This photo can be found at the Arkansas Geological Survey website under “Brachiopod.” They look a lot like clams. Brachiopods, often called lamp shells, have two shells and live in shallow marine environments just like clams and the occupy the same niche, feeding on organics filtered from the water. But unlike clams, which are molluscs, just like snails and squid, brachiopods are lophophorates, most closely related to bryozoans, the “moss animals.”.

Bryozoan lophophore. http://www.geol.umd.edu/

So what is a lophophorate? Lophophorate means “crest or tuft bearer, so named for their feeding apparatus called a lophophore, which is shaped like a roughly circular or semi-circular ring of tentacles. These tentacles lazily wave through the water passing through the lophophore, catching small particles of food suspended in the currents. Thus, everything in this group are what is known as suspension feeders. These lophophores serve not only to collect food, but for gas exchange as well. In addition, the animals are headless, with the lophophore surrounding the mouth. The food enters the mouth and passes through the digestive tract, which makes a U-turn and dumps out what it can’t digest just outside the ring of tentacles. Clams do essentially the same thing, only they use an entirely different apparatus to do so.

Clams attach themselves to surfaces by secreting a collection of what are called byssal threads. Most brachiopods, on the other hand, form a pedicle, a stalk that holds them in place. Some do not make pedicles, instead just gluing themselves down directly onto the rock.

Symmetry in a brachiopod and clam. http://www.kgs.ku.edu

Another difference that can usually be seen between clams and brachiopods is the symmetry of their shells. Brachiopods are symmetrical from side to side, their left side is the same as their right side. Clams follow a different pattern. They usually have two identical shells, but the shells themselves are not symmetrical. This is not always true though. The Cretaceous oyster, Exogyra ponderosa, has an huge, thick shell on one side and a thin lid for a shell on the other. But as a general rule, this usually works. Another difference that is sometimes stated is that brachiopods use their muscles to close their shells, while clams use their muscles to open their shells, closing them by the use of ligaments; thus making brachiopods more susceptible to predators. This, however, is not true. In truth, brachiopods use their muscles to both open and close their shells. Clams have large adductor muscles that function to close the shells and they have ligaments that open them when the muscles relax.

Brachiopods are quite diverse, with many different types. They range in size from less than a dime to almost 40 cm (15″). There are two general groups, the Articulates, which have toothed hinges holding the shells together, and the Inarticulates, which do not have teeth, so they fall apart easily after death. Probably the most commonly found in Arkansas are spirifers, known for being somewhat wing-shaped , with a prominent sulcus, or depression in the center. Many brachiopods prefer solid substrates, like rock, others were adapted for softer substrates like sand or mud.

Brachiopods are quite diverse, with many different types. They range in size from less than a dime to almost 40 cm (15″). There are two general groups, the Articulates, which have toothed hinges holding the shells together, and the Inarticulates, which do not have teeth, so they fall apart easily after death. Probably the most commonly found in Arkansas are spirifers, known for being somewhat wing-shaped , with a prominent sulcus, or depression in the center. Many brachiopods prefer solid substrates, like rock, others were adapted for softer substrates like sand or mud.  Productids, like the ones in our mystery fossil, often grew spines, which helped secure them to muddy surfaces. Others, like strophomenid brachiopods, handled muddy substrates by developing large, very flat shells, which floated on the mud like a snowshoe.

Productids, like the ones in our mystery fossil, often grew spines, which helped secure them to muddy surfaces. Others, like strophomenid brachiopods, handled muddy substrates by developing large, very flat shells, which floated on the mud like a snowshoe.  Still others, like the modern-day lingulids, developed long pedicles, allowing them to burrow down into the sediment.

Still others, like the modern-day lingulids, developed long pedicles, allowing them to burrow down into the sediment.

Brachiopods have been around since at least the Cambrian, over 520 million years ago. They were most abundant in the Paleozoic Era, but suffered greatly during the Permo-triassic extinction event. They recovered to some extent, but never reached their previous abundance due to the appearance of clams, which began taking over some of the spaces they occupied. Nevertheless, there are still several different kinds in the modern ocean and can often be seen clinging to rocks near shore or buried in the sand. In Arkansas, you won’t find any living specimens, but you can find numerous fossil brachiopods in the Paleozoic rocks throughout the Ozarks and Boston Mountains, even in some places of the Arkansas Valley. Stop by any outcrop along Highway 65 between Conway and the north edge of the state, particularly limestone outcrops, and you are likely to find some. You can find a few in the Bigfork Chert in the Ouachitas, but they are not nearly so common as they are farther north.

Mystery Monday

It’s Monday! Time for a new mystery fossil. See if you can guess what this is. Don’t clam up, put your guess in the comments below.

Fossil Friday, don’t be a wet blanket

Despite the snow, we didn’t get a chance to have any other posts this week other than the Monday Mystery fossil. We did, however, have three different school trips in the past couple of weeks to talk to kids about fossils, dinosaurs, and the skeletal system, as well as giving talks on the fossils telling us about the origins of crocodiles and dinosaurs, as well as attending a talk on the origins of birds. So a lot of paleo work, just not much showing up here. Fortunately, some of you had some time to examine our mystery fossil and congratulations to Laurenwritesscience for coming up with the correct answer.

It is indeed a stromatolite. Bruce Stinchcomb has a video on Youtube showing several examples of Ozark stromatolites and providing a good explanation of what they are.

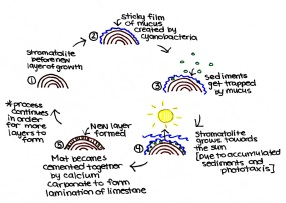

Essentially, stromatolites are microbial ecosystems, built up of layer after layer of microbial mats. The general description is that of blue-green algae, which forms a sticky layer over the surface of a rocky surface in a shallow marine or coastal environment. Blue-green algae are not actually algae and are better referred to as cyanobacteria. These bacteria are photosynthetic, just like plants, so they need sunlight, thus limiting the depth at which they can be found. Actually, they are typically found right at the water’s edge in the tidal zone. This sticky substance, while maintaining their hold on the rock, also tends to collect sand, clay, and organic debris. Over time, all the stuff that sticks to the mat blocks the sunlight from the cyanobacteria and they migrate above the layer and build another mat, which collects more debris, which causes them to build another mat, etc. Stromatolites form much the same way as piles of laundry. By the time you finish washing one set, there is another pile forming in a neverending stream. The life of a cyanobacteria in a stromatolite is a depressing condition of always digging themselves out from under a pile just to get dumped on again. I am sure most people can empathize.

The sticky mucus (properly referred to as extrapolymeric substance, or EPS for short, but we can go with mucus here) forming the mat does more than just cause things to stick to it. The mat protects the bacteria in from ultraviolet radiation. It also allows the bacteria to control the microenvironment around them, keeping such things as pH levels in a good range. It also has an unfortunate aspect for the bacteria. The mucus allows the levels of calcium and carbonate ions to build up until they precipitate out of the water as calcium carbonate, also known as calcite (when referring to the mineral), or limestone (when referring to the rock). So not only are the poor bacteria constantly getting buried, they are getting turned to stone in their very own medusa nightmare. Life is hard as a cyanobacteria. But just wait, it gets worse.

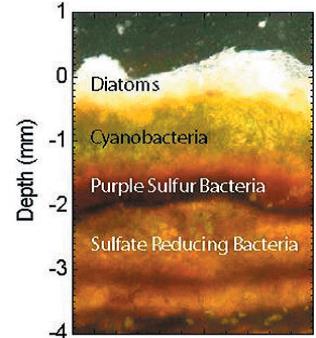

These microbial mats are not just cyanobacteria, though. There are lots of other organisms that live in and on them. There are many other types of bacteria. There are sulfate reducing bacteria, which use sulfur like we use oxygen, only they release hydrogen sulfide instead of carbon dioxide, causing a nice rotten egg smell. There are purple sulfur bacteria that eat the hydrogen sulfide, as well as colorless sulfur bacteria that eat both the hydrogen sulfide and the oxygen released by the cyanobacteria, thus free-loading off of everyone. In addition to bacteria, there are plenty of prokaryotes (organisms without nuclei that holds their DNA) and eukaryotic (with nuclei) single-celled and multi-celled organisms living in the mat. Diatoms, single-celled photosynthetic organisms that grow their own shell, live on top, while nematodes burrow through the mat. In addition to all this, a wide variety of animals love to chow down on the mats. Everything from snails, sea urchins, crabs, crawfish, and just regular old fish happily eat them. As a result, there are not a lot of places left in the world you can find stromatolites growing. The Bahamas and Shark’s Bay, Australia are the best areas to find them.

These microbial mats are not just cyanobacteria, though. There are lots of other organisms that live in and on them. There are many other types of bacteria. There are sulfate reducing bacteria, which use sulfur like we use oxygen, only they release hydrogen sulfide instead of carbon dioxide, causing a nice rotten egg smell. There are purple sulfur bacteria that eat the hydrogen sulfide, as well as colorless sulfur bacteria that eat both the hydrogen sulfide and the oxygen released by the cyanobacteria, thus free-loading off of everyone. In addition to bacteria, there are plenty of prokaryotes (organisms without nuclei that holds their DNA) and eukaryotic (with nuclei) single-celled and multi-celled organisms living in the mat. Diatoms, single-celled photosynthetic organisms that grow their own shell, live on top, while nematodes burrow through the mat. In addition to all this, a wide variety of animals love to chow down on the mats. Everything from snails, sea urchins, crabs, crawfish, and just regular old fish happily eat them. As a result, there are not a lot of places left in the world you can find stromatolites growing. The Bahamas and Shark’s Bay, Australia are the best areas to find them.

They may be rare now, but at one time, they ruled the earth. As some of the oldest living communities in the world, they have been around for at least 3.5 billion years (that’s 3,500,000,000, or roughly 600,000 times the length of human civilization) and for more 2/3 of that time, they were the only game in town and in all probability served as the cradle for all eukaryotic and multi-cellular organism on the planet. These days, if you live in Arkansas, the only places you can find them are as fossils in the Cambrian age Cotter Formation and Ordovician age Everton Formation in the Ozark Plateau.

They may be rare now, but at one time, they ruled the earth. As some of the oldest living communities in the world, they have been around for at least 3.5 billion years (that’s 3,500,000,000, or roughly 600,000 times the length of human civilization) and for more 2/3 of that time, they were the only game in town and in all probability served as the cradle for all eukaryotic and multi-cellular organism on the planet. These days, if you live in Arkansas, the only places you can find them are as fossils in the Cambrian age Cotter Formation and Ordovician age Everton Formation in the Ozark Plateau.

For further information (and the source of the images shown here), check out the stromatolite page at the Arkansas Geological Survey and the Microbe Wiki stromatolite page, as well as the Microbes.arc.nasa.gov site, which supplies a nice teacher’s guide to teaching all about microbial mats, designed for grades 5-8.

Mystery Monday, another snow time edition

I don’t know where you may be, but where I am, ice is covering everything and all the schools are closed. It’s a great day to pull up the covers and stay under the blankets, maybe get a cup of hot chocolate and wait for warmer weather. That makes today’s Mystery Monday fossil particularly apropos. Yes, this really is a fossil, not just layers of sediment.