Home » Posts tagged 'Paleontology' (Page 4)

Tag Archives: Paleontology

Dinosaur Odyssey: a Journey You Should Take.

Dinosaur Odyssey: Fossil Threads in the Web of Life

By Scott D. Sampson

Publication date 2009 (hardback) 2011 (paperback). 332 pg. University of California Press. ISBN: 978-0-520-24163-3.

Suitable for junior high students and up.

Author: Dr. Sampson is best known these days as Dr. Scott the Paleontologist, from Dinosaur Train on PBS KIDS (a children’s show I can recommend). But he doesn’t just play one on TV, he is a real-life paleontologist, and a well-respected one at that, best known for his work on late Cretaceous dinosaurs in Madagascar and the Grand Staircase-Escalante national Monument. He is Chief Curator at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science. He has a blog called Whirlpool of Life and can be found on Facebook. Dr. Sampson has had a longstanding interest in public science education, particularly about connecting children with nature. That interest is clearly evident in Dinosaur Odyssey.

Author: Dr. Sampson is best known these days as Dr. Scott the Paleontologist, from Dinosaur Train on PBS KIDS (a children’s show I can recommend). But he doesn’t just play one on TV, he is a real-life paleontologist, and a well-respected one at that, best known for his work on late Cretaceous dinosaurs in Madagascar and the Grand Staircase-Escalante national Monument. He is Chief Curator at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science. He has a blog called Whirlpool of Life and can be found on Facebook. Dr. Sampson has had a longstanding interest in public science education, particularly about connecting children with nature. That interest is clearly evident in Dinosaur Odyssey.

This book has been out a few years, but its main message is more deeply relevant now than ever before. This book is not really about dinosaurs. It is about the interconnectedness of all things. Dinosaurs are simply a fascinating hook for discussing ideas about evolution and ecology. If you are looking for a book that just talks about dinosaurs, look elsewhere. But if you want a book that puts dinosaurs in context as part of a complete and ever-changing ecosystem, if you want to learn about the Mesozoic world as a stage upon which dinosaurs are only a part, however awe-inspiring and prominent, of a much larger web of life, this book is for you. In Dr. Sampson’s hands, dinosaurs are not skeletons of bizarre creatures, they are living organisms interacting with others, changing and being changed by their environment. In a similar vein, our ideas about them are neither set in stone nor idle speculation, they are dynamic and changing, based on new discoveries and scientific understanding, circling ever closer towards a deeper understanding.

The book is written for someone with decent reading ability, but not a dinosaur aficionado. No real prior scientific knowledge is required, simply a desire to learn about the natural world. For those who want more, or find some of the terminology daunting, there is a wealth of notes and references at the end, along with a substantial glossary. The book begins with a short history of the scientific study of life and Sampson’s personal experiences searching for dinosaurs in Madagascar, which led to some of his thinking for the book as an introduction to what follows. Throughout the book, he uses his personal experiences to enrich the scientific discussions, making it a personal story, not just an academic one. Chapter two is an ambitious glimpse at the history of the universe until the dinosaurs appear, along with a short discussion of the geological principles forming the foundations of our understanding of geologic time. Chapter three introduces the dinosaurs, defining what is meant when a scientist talks about dinosaurs and the different groups of dinosaurs. Along the way, he discusses what species are, how they are named, and how we figure out relationships, although not in detail, just enough for a non-science person to understand the broad concepts. Chapter four discusses the physical world of the Mesozoic in terms of plate tectonics and how the movement of the continents shaped the world and thus the evolutionary history of dinosaurs. He even discusses the role of the atmosphere and oceans in climate. Chapter five builds the basics of ecosystems and nutrient flow, chapter six provides a background in evolutionary theory, chapter seven discusses how dinosaurian herbivores adapted to changing plant communities and how the dinosaur and plant communities may have co-evolved, each influencing the other. Chapter eight adds predators to the mix and chapter nine finishes the ecological chain with decomposers. Chapters ten and eleven discuss sexual selection and metabolism in dinosaurs.

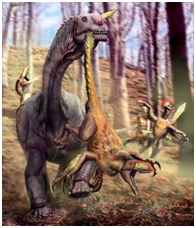

Michael Skrepnick contributed several paintings for the book, such as this one of Daspletosaurus attacking an Einiosaurus herd.

The chapters to this point built up how dinosaurs fit into the ecosystem and the workings of evolutionary theory. The next three chapters then take that information and discuss the dinosaurs rise to prominence in the Triassic, development of dinosaur ecosystems in the Jurassic, and their ultimate development through the Cretaceous period. Chapter fifteen, as might be expected, discusses the extinction ending the Mesozoic Era and the dominance of dinosaurs as major players on the world stage.

One might think the book would end at this point. But Sampson has one final chapter to go, which is probably the most important message in the book. He finishes the book by discussing why dinosaurs are important today. We are facing an extinction event equal to the end of the Cretaceous in terms of biodiversity loss, yet few people seem to notice just how comparatively depauperate our global ecosystems are becoming. Because dinosaurs draw peoples’ attention, they are the perfect tool to discuss evolutionary and ecological issues. In this chapter, Sampson discusses how to use dinosaurs to reach people and teach them about our own ecosystems, how we are affecting it and the problems we are facing. In this way, looking at our past through a dinosaurian lens can help us find our way forward.

In the final analysis, this book is a must-read for anyone interested in the natural world and how it works, especially if they love dinosaurs.

“Arkansaurus,” the only Arkansas Dinosaur

Welcome to the first of a series on Arkansas fossils. Arkansas is not generally known as a mecca for dinosaur lovers. Most of the dinosaurs in Arkansas are statues created by a man named Leo Cate, which have all the accuracy of the old plastic toys on which he based the statues, which is to say, not much (of course, he made them for enjoyment, not as anatomical models, so they serve their purpose). Nevertheless, dinosaurs are the first thing I get asked about when I give talks in schools, so I decided to start off with a discussion of our one and only dinosaur, called “Arkansaurus fridayi.”

Ordinarily, I would not delve into how a fossil was found here, but because Arkansaurus is unique and illustrative of how many fossils are brought to the attention of science, a brief synopsis of the story of how it was brought to the attention of science may be of interest. In August, 1972, Joe Friday was searching for a lost cow on his property near Lockesburg in Sevier County, when he found some bones eroding out of a shallow gravel pit. He showed them to a Mr. Zachry, whose son, Doy, happened to be a student at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville. Doy showed the bones to Dr. James H. Quinn, a professor at UA, who identified them as part of the foot of a theropod dinosaur. He contacted the Arkansas Geological Survey and Dr. Quinn, Ben Clardy of the AGS, and Mr. Zachry went back to the site where they found the rest of the bones. Dr. Quinn presented the bones at a meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology where he discussed the bones with Dr. Edwin Colbert, a noted paleontologist who was an expert in dinosaurs and vertebrate evolution. They came to the conclusion that the bones probably came from some type of ornithomimid, a group of ostrich-like dinosaurs (the name literally means bird-mimic), one of which, named Gallimimus, was made famous in Jurassic Park. Despite further excavations, no additional bones have been found. Dr. Quinn never officially described the bones, publishing only an abstract for a regional meeting of the Geological Society of America in 1973. It remained for Rebecca Hunt-Foster, now a paleontologist for the Bureau of Land Management, to publish the official description 30 years later in the Proceedings Journal of the 2003 Arkansas Undergraduate Research Conference.

Ordinarily, I would not delve into how a fossil was found here, but because Arkansaurus is unique and illustrative of how many fossils are brought to the attention of science, a brief synopsis of the story of how it was brought to the attention of science may be of interest. In August, 1972, Joe Friday was searching for a lost cow on his property near Lockesburg in Sevier County, when he found some bones eroding out of a shallow gravel pit. He showed them to a Mr. Zachry, whose son, Doy, happened to be a student at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville. Doy showed the bones to Dr. James H. Quinn, a professor at UA, who identified them as part of the foot of a theropod dinosaur. He contacted the Arkansas Geological Survey and Dr. Quinn, Ben Clardy of the AGS, and Mr. Zachry went back to the site where they found the rest of the bones. Dr. Quinn presented the bones at a meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology where he discussed the bones with Dr. Edwin Colbert, a noted paleontologist who was an expert in dinosaurs and vertebrate evolution. They came to the conclusion that the bones probably came from some type of ornithomimid, a group of ostrich-like dinosaurs (the name literally means bird-mimic), one of which, named Gallimimus, was made famous in Jurassic Park. Despite further excavations, no additional bones have been found. Dr. Quinn never officially described the bones, publishing only an abstract for a regional meeting of the Geological Society of America in 1973. It remained for Rebecca Hunt-Foster, now a paleontologist for the Bureau of Land Management, to publish the official description 30 years later in the Proceedings Journal of the 2003 Arkansas Undergraduate Research Conference.

The first thing to know about this particular dinosaur is that “Arkansaurus fridayi” is not its real name. In fact, it doesn’t even have an official name. The reason for this is because all we have of it is part of one foot. Specifically, we have the metatarsals, a few phalangeal bones, and the unguals. In non-science speak, on humans, they would refer to the bones making up the front half of your foot. The metatarsals are the long bones the toes are attached to forming the front part of the arch, the phalanges are the toes, and the unguals are the bony cores of the claws. The pictures show the actual bones and a cast, in which the missing phalangeal bones have been restored. The real fossil has all the phalangeal bones connecting to the metatarsals and all the unguals, but a couple of the middle phalanges are missing. We have no ankle bones and nothing at all of the rest of the animal. With such little to go on, it has been difficult to determine exactly what kind of dinosaur it is, so no scientist has been comfortable giving it an official name yet. To add to the complications, not a whole lot of feet from theropod dinosaurs are known, so good comparison material is limited, and little is known about theropods in the southern United States to begin with. (Aside: dinosaurs are separated into two groups. The Ornithischia, which are comprised of the herbivorous, mostly four-footed dinosaurs; and the Saurischia, which include the giant, long-necked sauropods and the bipedal, mostly carnivorous theropods.)

So why only one foot? What happened to the rest of it? I’ll let Rebecca Hunt-Foster explain it, as she did an excellent job: “There are several possibilities that would explain the occurrence of a single foot at the Friday site. It is a possibility that the rest of the Friday specimen could be gravel on highway 24. Road crews could have cut into the Trinity Group (Ed. Note. The rock formation in which the bones were found) when excavating the Quaternary gravel that lies directly above it, when building the road in 1954. As another theory, the animal may have begun to decompose before its body was carried by water to the site of deposition. Consequentlly, bits and pieces could have been scavenged by predators in the Lower Cretaceous, resulting in only a single foot remaining for preservation. Finally, it is possible that the entire specimen was preserved but that most of the skeleton was lost to Pleistocene erosion.” So just think about that the next time you go driving down the road. What fossils might you be driving upon?

Even if we don’t know for sure what it is, we do have some clues and can narrow down, at least a little, what it might be. What we know for sure is that it is some kind of coelurosaur. That, unfortunately, doesn’t help us a lot because coelurosaurs cover everything from little compsognathids to giant tyrannosaurs to modern birds, known principally for having bigger brains than earlier theropods, slender feet with three toes, and many of them had feathers. It does tell us it is not closely related to dinosaurs like allosaurs and spinosaurs, nor to early theropods like ceratosaurs and Coelophysis. Dr. James Kirkland opined that it was similar to Nedcolbertia, a small coelurosaur found in Utah. The problem here is that no one knows much more about Nedcolbertia either and its relationships to other dinosaurs are unclear. Quinn and Colbert thought it may have been an ornithomimid, but closer inspection by Rebecca Hunt-Foster and comparison with known ornithomimids indicates this is unlikely. Right now, all that can really be said is that it is likely a small coelurosaur, but not a tyrannosaurid, ornithomimid, or advanced form more closely related to birds, which leaves a small group of poorly known coelurosaurs no one really knows what to do with.

Even if we don’t know for sure what it is, we do have some clues and can narrow down, at least a little, what it might be. What we know for sure is that it is some kind of coelurosaur. That, unfortunately, doesn’t help us a lot because coelurosaurs cover everything from little compsognathids to giant tyrannosaurs to modern birds, known principally for having bigger brains than earlier theropods, slender feet with three toes, and many of them had feathers. It does tell us it is not closely related to dinosaurs like allosaurs and spinosaurs, nor to early theropods like ceratosaurs and Coelophysis. Dr. James Kirkland opined that it was similar to Nedcolbertia, a small coelurosaur found in Utah. The problem here is that no one knows much more about Nedcolbertia either and its relationships to other dinosaurs are unclear. Quinn and Colbert thought it may have been an ornithomimid, but closer inspection by Rebecca Hunt-Foster and comparison with known ornithomimids indicates this is unlikely. Right now, all that can really be said is that it is likely a small coelurosaur, but not a tyrannosaurid, ornithomimid, or advanced form more closely related to birds, which leaves a small group of poorly known coelurosaurs no one really knows what to do with.

Using these animals as a comparison, what can we say about what kind of animal “Arkansaurus” was? It was likely a fast runner with probably an omnivorous diet, eating smaller animals and supplementing its diet with plants. It would likely have stood somewhere between 2-4 meters (6.5-13 feet) tall. It would have looked something like an ostrich with long arms ending in hands with three functional fingers, with one of them being at least semi-opposable, and a jaw filled with small teeth. If it had feathers (which seems increasingly likely), the feathers would have looked more like fur than the large feathery plumage seen on ostriches today. It would also have had large eyes like ostriches, with excellent color vision, based on the fact that its nearest living relatives, crocodilians and birds, all see a broad spectrum of colors (even better than humans).

The rocks the bones were found in were part of what is called the Trinity Group. These rock layers (or strata) consist of layers of sand, clay, gravel, limestone, and gypsum laid down in the Early Cretaceous Period, roughly around 100-120 million years ago (what is known as the Albian and Aptian Ages). The rocks indicate that during the time the rocks were formed, the environment was a shallow marine coastal area not unlike south Texas near the Rio Grande or in the Persian Gulf. Our dinosaur would certainly not have been alone. There were other dinosaurs in the vicinity, we just know very little about them. Sauropods left thousands of tracks in the coastal sediment forming a massive trackway found in a Howard Country gypsum mine in 1983. Another trackway found in 2011 has tracks from sauropods such as Pleurocoelus and Paluxysaurus (which may or may not refer to the same species and may or may not also be called Sauroposeidon) as well as tracks from what was probably the giant theropod Acrocanthosaurus.

The rocks the bones were found in were part of what is called the Trinity Group. These rock layers (or strata) consist of layers of sand, clay, gravel, limestone, and gypsum laid down in the Early Cretaceous Period, roughly around 100-120 million years ago (what is known as the Albian and Aptian Ages). The rocks indicate that during the time the rocks were formed, the environment was a shallow marine coastal area not unlike south Texas near the Rio Grande or in the Persian Gulf. Our dinosaur would certainly not have been alone. There were other dinosaurs in the vicinity, we just know very little about them. Sauropods left thousands of tracks in the coastal sediment forming a massive trackway found in a Howard Country gypsum mine in 1983. Another trackway found in 2011 has tracks from sauropods such as Pleurocoelus and Paluxysaurus (which may or may not refer to the same species and may or may not also be called Sauroposeidon) as well as tracks from what was probably the giant theropod Acrocanthosaurus.

Most of the information and images in this post not directly linked to came from the following sources. Many thanks to Rebecca Hunt-Foster for clean pictures from her paper, which she also graciously supplied.

Hunt, ReBecca K., Daniel Chure, and Leo Carson Davis. “An Early Cretaceous Theropod Foot from Southwestern Arkansas.”Proceedings Journal of the Arkansas Undergraduate Research Conference 10 (2003): 87–103.

Braden, Angela K. The Arkansas Dinosaur “Arkansaurus fridayi”. Little Rock: Arkansas Geological Commission, 1998.

The top image is a Leo Cate T. rex. Photo by Debra Jane Seltzer, RoadsideArchitecture.com.

UPDATE: Arkansaurus has recently been named the Arkansas official state dinosaur, reviving interest in the fossil. It is currently being re-examined by Dr. Rebecca Hunt-Foster, with the hopes that new fossils and information that has come to light since her last publication will provide a more refined determination of its relationships.

Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages.

By Dr. Thomas Holtz, Jr. Illustrated by Luis V. Rey.

Publication date 2007. 427 pg. Random House. ISBN: 978-0-375-82419-7.

Author: Dr. Holtz, self-proclaimed “King of the Dino Geeks,” or as I like to call him Dr. Tyrannosaur, is a well-known and respected paleontologist who’s understanding of all things tyrannosaur is unparalled. As a senior lecturer at the University of Maryland and the Faculty Director of the Science & Global Change Program for the College Park Scholars, he has extensive teaching experience. I have had the pleasure of attending several of his talks at meetings of the Society for Vertebrate Paleontology and he has always been informative and interesting and his students have always been very positive about him.

Illustrator: Luis Rey is an accomplished and respected artist, known especially for his paleo art. He has won the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Lazendorf Award, given to outstanding artists and his artwork can be seen in several museums, books, and other outlets. He is known for very colorful dinosaurs with close attention to anatomical detail. He makes huge efforts to bring dinosaurs to life as actual, living creatures with as much accuracy as possible. A few have criticized his artwork for being too fanciful, in that he draws wattles and other structures on dinosaurs for which we have no hard evidence. But these structures are extremely difficult to preserve in fossils and their living relatives do have them. Matt Wedel, a noted dinosaur researcher in his own right (although he studies sauropods, not theropods like Dr. Holtz) has said, “If you go bold, you won’t be right; whatever you dream up is not going to be the same as whatever outlandish structure the animal actually had. On the other hand, if you don’t go bold, you’ll still be wrong, and now you’ll be boring, too.” Luis Rey has never been called boring.

Illustrator: Luis Rey is an accomplished and respected artist, known especially for his paleo art. He has won the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Lazendorf Award, given to outstanding artists and his artwork can be seen in several museums, books, and other outlets. He is known for very colorful dinosaurs with close attention to anatomical detail. He makes huge efforts to bring dinosaurs to life as actual, living creatures with as much accuracy as possible. A few have criticized his artwork for being too fanciful, in that he draws wattles and other structures on dinosaurs for which we have no hard evidence. But these structures are extremely difficult to preserve in fossils and their living relatives do have them. Matt Wedel, a noted dinosaur researcher in his own right (although he studies sauropods, not theropods like Dr. Holtz) has said, “If you go bold, you won’t be right; whatever you dream up is not going to be the same as whatever outlandish structure the animal actually had. On the other hand, if you don’t go bold, you’ll still be wrong, and now you’ll be boring, too.” Luis Rey has never been called boring.

I decided to start off my reviews with this book, even though it has been out since 2007, because I think every school should have it. There are good reasons it won “Outstanding Science Trade Books for Students K to 12: 2008 by the National Science Teachers Association. It is called an encyclopedia and it does have chapters describing all the various dinosaur groups, but it is so much more. It is not a small book and here is my only real criticism of the book. Despite its title, it is not quite a book for all ages (School Library Journal rated it Grade 5 and up and it would take an exceptional 5th grader to read it). If you are looking for a book to read to little kids, look somewhere else. It is called an encyclopedia for a reason. Nevertheless, with that caveat in mind, if you are looking for a book to give your dinosaur-obsessed kid who can read well, this book is for you. It is not just for kids though. Adult dinosaur enthusiasts will like it too.

What I like best about this book is that it does not simply focus on the dinosaurs. There are plenty of books that will give you an A-Z description of dinosaurs. Holtz gives the reader a feel for what paleontology is and how it works. The goal of this book is to explain why we think what we do about them, how we know what we know. He starts off the book discussing how science, particularly as it applies to paleontology. He then has a chapter on the field’s history, followed by three chapters of geology and geologic time to put everything into perspective. Chapters 5-9 discuss how paleontologists find fossils and attempt to reconstruct what they looked like and how they are related to each other. It is not until chapter 10 that he even starts talking about dinosaurs themselves and that chapter simply explains how they are related to other vertebrates. Chapters 11-35 are the meat of the book that everyone would expect. This is where he discusses the amazing diversity of dinosaurs. The last five chapters discuss dinosaur behavior and metabolism and how we approach topics like this that are not so easy to see in the fossils. The last three chapters then put the dinosaurs in context of time and ecology. Contrary to popular opinion, dinosaurs did not all live at the same time. They spanned a vast length of time and these chapters give the reader some sense of what the earth was like during the major time periods, who lived when and what other animals they lived with. The last chapter ends predictably with a discussion of extinction, but rather than just say the asteroid killed them all off, Holtz discusses some of the complications of that hypothesis, finishing off with how life continued after the asteroid impact (including the dinosaurs, who were only mostly dead, not completely dead, a few made it through and thrived as birds). At the end of the book is a series of tables listing all the dinosaurs, including where and when they lived and their estimated size and weight.

What I like best about this book is that it does not simply focus on the dinosaurs. There are plenty of books that will give you an A-Z description of dinosaurs. Holtz gives the reader a feel for what paleontology is and how it works. The goal of this book is to explain why we think what we do about them, how we know what we know. He starts off the book discussing how science, particularly as it applies to paleontology. He then has a chapter on the field’s history, followed by three chapters of geology and geologic time to put everything into perspective. Chapters 5-9 discuss how paleontologists find fossils and attempt to reconstruct what they looked like and how they are related to each other. It is not until chapter 10 that he even starts talking about dinosaurs themselves and that chapter simply explains how they are related to other vertebrates. Chapters 11-35 are the meat of the book that everyone would expect. This is where he discusses the amazing diversity of dinosaurs. The last five chapters discuss dinosaur behavior and metabolism and how we approach topics like this that are not so easy to see in the fossils. The last three chapters then put the dinosaurs in context of time and ecology. Contrary to popular opinion, dinosaurs did not all live at the same time. They spanned a vast length of time and these chapters give the reader some sense of what the earth was like during the major time periods, who lived when and what other animals they lived with. The last chapter ends predictably with a discussion of extinction, but rather than just say the asteroid killed them all off, Holtz discusses some of the complications of that hypothesis, finishing off with how life continued after the asteroid impact (including the dinosaurs, who were only mostly dead, not completely dead, a few made it through and thrived as birds). At the end of the book is a series of tables listing all the dinosaurs, including where and when they lived and their estimated size and weight.

Holtz doesn’t go it alone either. Scattered throughout the chapters are inserts from other researchers (such as Dr. Kristi Curry Rogers shown here) explaining various topics related to their own research, so the reader gets the perspective of many paleontologists, not just the author’s.

Holtz doesn’t go it alone either. Scattered throughout the chapters are inserts from other researchers (such as Dr. Kristi Curry Rogers shown here) explaining various topics related to their own research, so the reader gets the perspective of many paleontologists, not just the author’s.

A serious bonus for this book is that Dr. Holtz has attempted to keep the book as current as possible by posting online corrections necessitated by new research, which you can find here.

As a final word, the book is superbly illustrated with numerous drawings, both in monotone and vivid color, by Luis Rey. There are no images of actual fossils, which some have criticized the book for, but my personal feeling is that the book was not designed to be a textbook for dinosaurs. It was designed to show the dinosaurs as living animals, not simply as their bones. There are plenty of other places one can find that. This book is for a view of what they were like alive and most importantly, why we think they were like that shown here and how we study them.

As a final word, the book is superbly illustrated with numerous drawings, both in monotone and vivid color, by Luis Rey. There are no images of actual fossils, which some have criticized the book for, but my personal feeling is that the book was not designed to be a textbook for dinosaurs. It was designed to show the dinosaurs as living animals, not simply as their bones. There are plenty of other places one can find that. This book is for a view of what they were like alive and most importantly, why we think they were like that shown here and how we study them.

For other reviews of this book, try here, here, here, and here, among others. All illustrations above can be found within the book, as well as the linked sites for Luis Rey and Dr. Rogers.