Home » 2015 (Page 3)

Yearly Archives: 2015

Species of the Dead

National Geographic has a website called Phenomena, which is the home to a group of blogs, one of which is Laelops, a blog written by Bryan Switek devoted to paleontology, with a considerable emphasis on dinosaurs. Recently he wrote an essay on Lazarus taxa. That got me thinking about how species can appear to disappear and reappear in the fossil record and the strange and funny ways scientists talk about species, so this post will expand upon that topic and discuss ways that species can appear to come back from the dead, figuratively speaking.

What is a Species?

First off, it is important to understand what we mean by a species. Most people think of species using the biologic species concept, which requires a species to be reproductively isolated, the species is defined by who can breed with who. Unfortunately, there are a number of instances in which this doesn’t work. There are species that do not reproduce by having two individuals of different sexes breed, such as some parthenogenic frogs and fish, in which the females create viable eggs without the need of a male. Bacteria, which reproduce by simply dividing, can’t be called species this way, especially since they exchange DNA on a regular basis. Fertile hybrids screw up the biologic species concept as well and are much more common than most people realize. For paleontologists, the biggest problem is that we have no way of knowing how well fossil species could mate because fossils aren’t known for their breeding potential, being dead and all.

In fact, there are at least 26 different published concepts of what a species actually is. As a result, researchers have to choose the one most applicable to their research. Paleontologists frequently use what is known as the morphospecies concept. If it looks sufficiently different, we call it a different species. Are there problems with this? Yes, but we are limited by the data we have. We just have to keep in mind that paleospecies are not the same thing as modern species.

Gaps in the Record

The fossil record is quite good for many types of organisms, not so good for others. As a result, there are gaps in our knowledge. Sometimes a fossil can disappear from the fossil record and appear to go extinct only to reappear millions of years later. These species are called Lazarus taxa (a taxon, pl. taxa, is the name for a generic taxonomic unit, be it species, family, order, etc.). If one is familiar with the biblical story of Lazarus, the name makes sense. Lazarus died and was brought back from the dead. In a conceptually similar manner, taxonomists can bring a species back from “extinction” by finding more fossils, or, in some cases, living representatives.

Lazarus taxa can be formed a variety of ways. There may simply not be any rocks of the right age where the organism lived to preserve fossils, either through erosion or never having been laid down in the first place. It could be that they simply haven’t been found yet. The organisms could have moved so they are no longer in the same spot. For instance, crinoids at one time lived throughout shallow marine areas and were quite abundant. Almost all of them died out at the end of the Paleozoic. One group survived, but are most common in deep water and are much less common in shallow marine areas, making their fossils after the Paleozoic few and far between.

The most commonly discussed Lazarus fossil is the coelacanth, a fish whose fossil record had ended at the end of the Mesozoic and was presumed extinct, until live ones were caught in the Indian Ocean near South Africa and Indonesia. They were another species which seems to have retreated to deep water refuges to avoid complete extinction.

The most commonly discussed Lazarus fossil is the coelacanth, a fish whose fossil record had ended at the end of the Mesozoic and was presumed extinct, until live ones were caught in the Indian Ocean near South Africa and Indonesia. They were another species which seems to have retreated to deep water refuges to avoid complete extinction.

Come out, We Know You’re There

A related concept is that of ghost lineages. For Lazarus taxa, we know the species was present, we just haven’t found them yet. Obviously, if coelacanths were alive in the Cretaceous and today, they must have lived in between as well. Sometimes the gaps get filled in by discoveries of new fossils, others are still waiting to be found. Ghost lineages cover any situation in which we know a taxon had to exist, but we have no evidence for it, so Lazarus taxa can be thought of as a subset of ghost lineages. For Lazarus taxa, it is that gap between one fossil range and a much later one. But there is also the situation wherein a taxon had to exist much earlier than for which we have a record; and it is in these situations ghost lineages are most commonly invoked.

Three taxa represented in the fossil record are hypothesized to be related to each other in a certain way. When the occurrences of these taxa in the fossil record are plotted against time, then the apparent gaps in the fossil record can be explained by ghost lineages. http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/taxa/verts/archosaurs/ghost_lineages.php

Suppose we have two taxa that we think are closely related. They had to have then had a common ancestor which lived before either taxa, even if we have no evidence for it. Everyone knows they have a great-great-grandfather even if they don’t know who it is. In the same way, every species has to come from a preexisting species even if there are no fossils proving its existence. It is also devilishly hard to determine an ancestral species (so hard in fact that many researchers view the best course is to just assume we can never do so), so we may even have found it already and just not recognized it as such, but that is a topic for another day. Unlike your ancestors though, the fossil record for related species can be separated by tens of millions of years. This range in which we have no fossil records for the species that existed later in time and for the ancestor itself is referred to as a ghost lineage.

Will the Real Taxon Please Step Forward

Another weird fossil species concept is that of Elvis taxa. After Elvis died, huge numbers of impersonators appeared. They may look like Elvis, they may sound like Elvis, but they are not Elvis. Species can do the same thing. When one species dies out, they can sometimes be replaced by a species that fills the same niche and may even look superficially similar, but they are unrelated. When two or more species develop in the same, at least superficially, ways, we call that convergent evolution. The pangolin, anteater, aardvark, and echidna (the spiny anteater) are all similar with similar lifestyles, but none of them are closely related to any of the others. If we apply this convergence to the fossil record, we can sometimes find a species that goes extinct, but is replaced by another species that fills the same niche, thus impersonating the previous taxon. If the two taxa are separated by time, they might appear to be Lazarus taxa, but they aren’t really because they are not the same species.

Bring Out Your Dead

Then there are the zombie species. Zombies are taxa that have gone extinct and fossilized, but the rocks encasing the fossils gets eroded. Sometimes, the fossil can then get reburied in new sediment, which becomes lithified, forming a new sedimentary rock layer. The fossil then appears to be the younger age of the new rock even though it is in reality much older. This can happen most commonly with teeth because the enamel is very resistant to weathering. So if you find isolated teeth, they may not have actually originated in the rock in which you found them. You may have just found a zombie. A number of such zombies, or reworked fossils, have been found in the form of dinosaur teeth in the early Paleocene, after the mass extinction event that wiped out all the nonavian dinosaurs.

Finally, there is the Dead Clade Walking. These are species that are extinct, they just don’t know it yet. This can happen after a mass extinction in which most species die out, leaving a few stragglers, which limp along for a while, but eventually succumb. After the Permian mass extinction, anomodont therapsids, the most famous being Lystrosaurus, survived the extinction that killed so many others Unfortunately for them, the group did not thrive, instead dwindling down until they too went extinct (if one follows the dinosaur teeth, you will find discussion of a possible dinosaur dead clade walking example). Lystrosaurus itself did spectacularly well and survived well into the early Triassic. So well, in fact, that that some places even have a “Lystrosaurus zone” because of all the fossils of them in the layer. As a result, Lystrosaurus is often called a “survivor taxon”. Even so, it too dwindled and went into the west, went extinct. A better group that deserves the survivor label is the cynodonts. They were minor players in the Permian, but after the great extinction event, they prospered, taking over the world in the early Triassic, at least until they crashed in the late Triassic and were replaced by the dinosaurs.

You Don’t Know Darwinian Evolution (Or Maybe You Do)

Yesterday was Darwin’s birthday. So instead of trying to shoehorn some sort of Valentine’s Day themed post for the week or an article about Darwin and his life and the importance of evolutionary theory, I thought I would briefly discuss a few of the most common Darwinian myths I have heard. For most people, it seems, it is accurate to say You Don’t Know Darwin, or Evolution, or Darwinian Evolution.

1. I don’t believe in evolution.

Yes, you do. You just don’t know it because you’ve been lied to by people who don’t understand evolution either and are threatened by it. But before we get into that, let’s please dispense with the term “belief”. Belief requires faith with no evidence. Since there are mountain-loads of evidence for evolution, don’t believe in it. Accept the evidence all around you. Once you understand what evolution is, you will agree that you have to be brain damaged not to accept it is true. Here is the big secret. Here is the definition of evolution.

Change over time.

Let me hear you say it!

Change over time.

I can’t hear you!

Change Over Time!

That’s it. See? Not so painful. You’d have to be an idiot not to understand that things change. If nothing ever changed, we would have no history books and people could never complain about the “good old days” when students were better (yes, people have complained that today’s students are worse than the previous generation for literally over 3000 years, one can only assume that either the ancient Greeks were God-like brilliant or people are biased).

What’s that, you say? That’s not what evolution means? Well, yes, it really is. But you want to talk about biological evolution. Some people think that simply saying change over time is overly simplistic and doesn’t really describe biological evolution. Ok, then. Here is a better definition of biological evolution. Ready?

Descent with Modification

Seriously, that’s it. Children are different from their parents. Now, unless you are going to argue that you are exactly the same as your parents, that everyone is in fact a clone, you are an evolutionist. Congratulations.

Oh alright. You may have heard that individuals don’t evolve, only populations, or even species. What that means is that one does not evolve over the course of one’s own lifetime. For most organisms, that is true. Of course, if you are a plant, which has what is termed modular growth, that is not strictly true. Plants can reproduce through one of two methods. They can reproduce through seeds, or they can reproduce through vegetative growth. In vegetative growth, the plants can send out tendrils (many people might call such tendrils “roots”). Those tendrils can grow horizontally through the soil and then spring up to grow what appears to be a new plant. The new plant is often called a clone, thus some people refer to this as clonal growth. Cottonwoods and sumac are great examples of this, most of them you see are actually clones grown this way. I say clones, but that does not necessarily mean they are genetically identical. If a mutation occurs at some point in one of the cells in that root tip, it can get passed along through the continued growth of that root so that the clone is indeed slightly genetically different. Considering that some of these plants can grow vegetatively for thousands of years through thousands of “clones”, a fair bit of genetic diversity can occur from one end to the other. I mentioned earlier that this is called modular growth. It gets that name because mutations that occur at the root tips affect all growth after that point, but do not affect the part of the plant before that point. Different parts of the plant are effectively separated from each other genetically and, to a point, physiologically. This is why you can grow new plants from cuttings. If the plant didn’t have modular growth, you couldn’t do this. Just imagine cutting an arm off of a person and trying to grow a new body from the arm. Animals, like us, do not generally have modular growth (unless you are a starfish, or planaria, or…).

Many people prefer a definition of biological evolution that takes populations into account. Thus, you will find this definition in many places.

A change in gene frequency in a population over time.

In this definition, evolution is restricted to changes that affect the DNA throughout a population. Ok, fine. But what does that really mean to a nongeneticist? It means that populations change over time in a way that those changes can be passed on to offspring. This is different than, say, changes in height and weight through strictly dietary changes. Just because Americans eat more and are thus typically taller and fatter than people in most other countries does not mean we have evolved to be taller and fatter, it just means we eat too much. It shouldn’t take a genius to realize this is true. A great example of evolutionary change in humans is our wisdom teeth, otherwise known as our third molars. Does it make any sense to anyone that we were created with jaws too small to fit all of our teeth so that we wind up having to pull some out? No, that’s ridiculous. The reason that our jaws are shrinking is that we have switched from eating tough, raw foods to softer, cooked, and processed foods that are easier to digest and we no longer have to chew as much. Some people are now being born who never have wisdom teeth. Eventually no one will have wisdom teeth and orthodontists will be very sad as a good chunk of their income will be lost to evolution.

But what really defines a population? It should be clear by now that biology does not lend itself to neat little boxes. Biology is messy (if it stinks, it is probably chemistry, but that’s another discussion). Typically, a population is defined as a set of individuals capable of interbreeding. This is very much like the biological species concept (BSC). The difference is that a species can be divided into multiple populations because not every member of a species has access to every other member. If something gets in the way, you get separate populations of the same species. And here we have a problem. What is a species? Most people have heard about the BSC. Unfortunately, it doesn’t work for a lot of organisms. It doesn’t work for plants, who hybridize at the drop of a hat and can grow vegetatively anyway. It doesn’t work for bacteria, or parthenogenic species who only need females to reproduce, or animals that can be cut up like sponges and starfish and planaria, etc. The last time I counted, there were 26 different definitions of a species. The idea that a species is the only “natural” unit in taxonomy is a myth. Even species are not natural. Researchers use the definition that is most applicable to their research. For instance, paleontologists can’t possibly use the BSC. It is really hard to get fossils to breed. Some might even say impossible. As a result, paleontologists are stuck with what is called the morphospeces concept. If it looks sufficiently different, it’s a new species. This means of course that you can’t realistically compare modern and fossil species because they don’t mean the same thing.

This is a really long-winded way of saying that it is much better to talk about evolutionarily discrete lineages, rather than populations or species and why I prefer sticking with the “descent with modification” definition of biological evolution. If that seems harder to deal with, biology is messy. Get used to it. But just because it is messy doesn’t mean it’s wrong. Life is usually messy. Just ask any parent. If you want absolutes and certainty, go talk to a physicist. Biologists have to deal with the real world in all its chaotic mess. I envy physicists, I really do. They have it easy. Yes, physics is easy. Biology is hard.

Ok, that was a lot. But if you still say you don’t believe in evolution, you are deluding yourself. The other myths can be dealt with much more succinctly.

2. You have to be atheist to believe in evolution. Darwin was an atheist until he converted on his deathbed.

I hear that a lot, but seriously? Are you seriously going to sit there and tell me these guys are atheists? Ok, maybe the last one, but this is an issue of pitting one faith against another, so please pardon the joke.

The last three Popes. http://wydcentral.org/

If you can’t trust that the Popes are devoutly religious, you have serious issues. But say you are one of those people that say the Popes may be religious, but they are going to Hell because they aren’t your sect of religion. Ok. Dr. Francis Collins is the head of the National Institute of Health. He led the Human Genome Project. He also happens to be an outspoken Evangelical Christian and has written extensively on why evolution does not conflict with Christianity. But Dr. Collins is a scientist, what does he know? What about Pat Robertson, leader of the 700 Club? Surely we can all agree that if Pat Robertson, of all people, does not think that evolution conflicts with Christianity, we can agree that you do not need to be an atheist to accept evolution.

Ok, you say that Pat Robertson is crazy. I won’t argue with you. But what about Billy Graham? If there is anyone more respected in the Evangelical Christian community, I don’t know them. Billy Graham has no problem with evolution. He is clearly not an atheist.

What about Darwin being an atheist? No, he wasn’t. He actually thought about going into the seminary to become a minister, but decided against it to pursue his academic interests. He didn’t seriously begin questioning his faith until his ten-year-old daughter died. After that, he lost faith in any sort of benevolent deity and he never recanted. The story that he converted to Christianity and denounced his views on evolution on his death bed is complete fiction. It was made up by someone who wasn’t even there. Why Lady Hope made up this story, I can’t say, but it is definitely a fraud. The important point here is that at no time did Darwin ever think that evolution conflicted with the Bible.

3. Evolution says that we evolved from monkeys, which can’t be true because A) I’m not a monkey, eww; and B) monkeys still exist.

Tell me, do most mothers die in childbirth? Then why would anyone think that a species has to go extinct when a new species arises? The reason that people think this is because they still have this view of the Great Chain of Being,” which was an old Christian view that everything had its place in the universal order. Rocks were at the bottom, then plants, then lowly animals, on up to humans being the most important mortal thing in all of Creation, topped only by the Heavenly Hosts, Jesus, and God Himself (that bit always confused me, if God is male, then there should be a female God, so where is She? Nevermind, I digress, that’s a whole other discussion.) Anyway, with this view in their head, people naturally assume that evolution works the same way. One species should naturally transform somehow into a new species.

Peripheral isolates. Taxon A is the original species. B-F are new species that evolved from the original species due to adaptation for the particular environments in that area. The original species is usually more of a generalist, able to survive in many environments.

Except it doesn’t work that way. Not all individuals of a species have to evolve together. If that species is divided into separate populations, or evolutionary discrete lineages, each population could evolve into a separate species. The original, or parent species, never has to change at all. Take the peripheral isolates concept. In this case, there is a species that has a broad range. At the edges of the range, members of the species find themselves in a different environment from the members of the species in the center of the range. The population exposed to the new environment will evolve in response to that environment, but the population in the center of the population never has to change. Thus, you have two or more species evolving from an original species that is still present.

But what about humans evolving from monkeys? No, that isn’t technically true either. Again, using the family analogy, let’s say your parents had siblings. Your aunts and uncles had kids of their own. You are related to your cousins through your parents. Pretty straightforward, right? Now replace everyone with species. You and all your cousins would be individual evolutionarily discrete lineages, you all have your own evolutionary path. Now, say that you represent all humans and your cousins represent all the species of monkeys. You aren’t a monkey, neither are your parents. your cousins, on the other hand, are (sorry, cuz). You (meaning all humans) share a common ancestor (your parents, or the ancestral species of humans) with your cousins (all the monkeys).

4. Evolution says that the earth is really, really old.

No, evolution has nothing to do with how old the earth is. The geologic time scale was actually put together by people correlating different rock units based on their relative position. Using the Law of Superposition, the oldest rocks were at the bottom, with the youngest rocks on top. Examining the rocks from place to place, they were able to line up different rock units into a long column. But it was all relative. They had no idea how old the rocks were. Finding the age of the earth didn’t happen until physicists discovered radioactivity. Some very smart physicists figured out that they could use the rate of radioactive decay to date rocks. All paleontologists and evolutionists did was say Thank You! So if you don’t like the age of the earth being over 4.5 billion years old, go talk to the physicists, it has nothing to do with evolution. Of course, when you do talk to them, you will have to deal with the fact that they have tested the theories quite well. We know they work because if they didn’t, we would not have nuclear bombs, nuclear power plants, x-ray machines, and a whole host of other things that work because of our understanding of radioactivity.

5. How does evolution explain the origin of life?

Easy, it doesn’t. Evolution only works on life that already exists. If you want to complain about the origins of life, go talk to a chemist. The origins of life is a chemical and physics problem, it has nothing to do with evolution.

5.Darwin invented evolution.

The last one for today might surprise people the most. Darwin did not invent, discover, or in any way introduce evolution. People knew that organisms change long before that. Joseph Buffon discussed the mutability (change) of species and that they had common ancestors in the 1700s. What Darwin did was provide a plausible mechanism for how evolution worked. Darwin provided evidence for natural selection. Of course, Darwinian evolution via natural selection is not the only mechanism. There is gene flow, which involves new material being introduced by immigrants into a population, and genetic drift, which is simple, boring, old random chance. But that is a topic for another day.

New Book on the Solnhofen Limestone

This is just a quick post to point you to a review by Darren Naish. Darren has done a fair bit of research on pterosaurs and Mesozoic birds. He also spends a good amount of his time writing for the general public with several good books out. The reason I am saying this is to make it clear that his opinion on this book is far more important and knowledgeable than mine.

Matthew P. Martyniuk’s Beasts of Antiquity: Stem-Birds in the Solnhofen Limestone is a book on the pterosaurs, archaeopterygians, and a dinosaur that, as the name suggests, have been found in the Solnhofen Limestone. This formation is well known because one of the most famous fossils of all time was found there, that being Archaeopteryx, a fossil that has been used to clearly demonstrate the link between dinosaurs and birds. If this sort of book is interesting to you, read Naish’s review.

Mystery Revealed: A Common Coral in Arkansas

It is the unfortunate fact of life that volunteer efforts are all too often derailed by other pursuits. Such is the case for last week’s Mystery Monday fossil. Nevertheless, the answer shall be forthcoming. If you have been paying attention to the Facebook feed, you will know that the fossil presented last Monday was identified. Were you able to figure it out?

This is a large, very well preserved piece of tabulate coral. Corals are colonial species that are very important in modern ecosystems. A fourth of all ocean species live within these reefs. They form the backbone of reefs that are among the richer areas of biodiversity on the planet. Billions of dollars each year are pumped into local economies across the world.

What we think of as coral is mostly the calcareous homes they form, within which the animals live. The actual animal is a tiny animal in the Phylum Cnidaria. Cnidarians are soft-bodied animals, the best known of which are the jellyfish and sea anemone. Cnidarians take two general forms. Medusae are free-floating forms like the jellyfish. Coral and sea anemones are polyps, mostly stationary, or “sessile”, forms that remain in place their entire lives. Corals, like other cnidarians, are predatory, catching their prey with tentacles armed with nematocysts, cells containing potent poisons to immobilize or kill their prey. Of course, since corals are tiny creatures themselves, they prey on even tinier prey. The tentacles surround an opening which serves as both mouth and anus, basically making the animal a living, carnivorous sack. This is not the only way corals get food though. Most modern corals also have a symbiotic relationship with single-celled algae called zooxanthellae, which provide essential nutrients for the coral in which they live. Unfortunately, when the coral gets too stressed from increasing temperatures or other causes, they tend to respond by evicting the zooxanthellae. Because the zooxanthellae are what gives corals their bright colors, this is known as coral bleaching.

While there are several different kinds of coral, most of the coral people are familiar with are the stony corals, or Scleractinia, because these are the ones that build the reefs. They are part of the larger group of corals known as Hexacorallia (at least, if you are talking to modern biologists, paleontologists often restrict Hexacorallia to scleractinians), known for often having the individual coral homes partially divided with six partitions, or septa (although you may be hard pressed to identify the three axes forming the six partitions even if they are present in that number).

The scleractinians have only been around since the Mesozoic however. They did not build the coral reefs of the later Paleozoic Era. That distinction goes to the rugose, or horn, corals and the tabulate corals, such as the example above. Tabulate corals are known for the corals being aligned in horizontal stacks. The image above should really be rotated 90 degrees to get the life position. This stacking always reminds me of apartment building, particularly cheap tenement housing, or wire mesh. According to phylogenetic studies on modern corals, it appears that the earliest scleractinians did not have zooanthellae, the symbiotic relationship evolving later, so it seems likely tabulate corals didn’t either. Tabulate corals appeared in the Ordovician Period roughly 450 million years ago. They started dying out in the Permian and finally succumbed to extinction at the end of the Permian period 252 million years ago, along with most other life on the planet. However, it is a bit misleading to say they went extinct. It is thought that the modern scleractinians that arose in the early Triassic are descended from tabulate corals, so they appear to have evolved, rather than just died out.

If you want to find corals such as this in Arkansas, one need only travel anywhere in most of the northern part of the state. The Ozark Mountains are predominantly formed from shallow marine Paleozoic rocks. Anywhere you find limestone in the Ozarks, keep your eyes peeled for samples of this type of coral. They are invertebrates, so as long as you are not collecting in a National Forest or private property without the owner’s permission, you are free to collect them.

What has evolution done for me lately?

“I have a dream…”

Almost everyone will have heard this most famous line by Martin Luther King, Jr. in the past few days. In honor of the holiday, rather than introduce another fossil, review a book, or some such thing, I thought I would do something a little different. I have a dream too, one in which teachers are not afraid to talk about evolution within the classroom, one in which people don’t recoil from the word because they think it goes against their religion, a dream in which everyone embraces the concepts, not because some scientist or teacher tells them they have to, not because they think it is part of a body of education they need to sound smart, but because they see the logic of evolutionary theory and the application of it in their everyday lives, because they understand how it affects them every day in ways they normally never even think about. In this essay, I am going to discuss a few of the many ways evolutionary theory helps us in practical applications. Next post I will discuss why I think most people deny evolution (it’s not what most people say, what people say and really think are often entirely different things), and why that denial is something we need to get past.

Cancer is an inescapable fact of life. All of us with either die from it or know someone who will. Cancer is so prevalent because it isn’t a disease in the way a flu or a cold is. No outside force or germ is needed to cause cancer (although it can). It arises from the very way we are put together. Most of the genes that are needed for multicellular life have been found to be associated with cancer. Cancer is a result of our natural genetic machinery that has been built up over billions of years breaking down over time.

Clonal evolution of cancer. Mel Greaves. http://www.science-connections.com/trends/science_content/evolution_6.htm

Cancer is not only a result of evolutionary processes, cancer itself follows evolutionary theory as it grows. The immune system places a selective pressure on cancer cells, keeping it in check until the cancer evolves a way to avoid it and surpass it in a process known as immunoediting. Cancers face selective pressures in the microenvironments in which they grow. Due to the fast growth of cancer cells, they suck up oxygen in the tissues, causing wildly fluctuating oxygen levels as the body tries to get oxygen to the tissues. This sort of situation is bad for normal tissues and so it is for cancer, at least until they evolve and adapt. At some point, some cancer cells will develop the ability to use what is called aerobic glycolysis to make the ATP we use for energy. Ordinarily, our cells only use glycolysis when they run out of oxygen because aerobic respiration (aka oxidative phosphorylation) is far more efficient. Cancer cells, on the other hand, learn to use glycolysis all the time, even in the presence of abundant oxygen. They may not grow as quickly when there is plenty of oxygen, but they are far better than normal cells at hypoxic, or low oxygen, conditions, which they create by virtue of their metabolism. Moreover, they are better at taking up nutrients because many of the metabolic pathways for aerobic respiration also influence nutrient uptake, so shifting those pathways to nutrient uptake rather than metabolism ensures cancer cells get first pick of any nutrients in the area. The Warburg Effect, as this is called, works by selective pressures hindering those cells that can’t do so and favoring those that can. Because cancer cells have loose genetic controls and they are constantly dividing, the cancer population can evolve, whereas the normal cells cannot.

Evolutionary theory can also be used to track cancer as it metastasizes. If a person has several tumors, it is possible to take biopsies of each one and use standard cladistic programs that are normally used to determine evolutionary relationships between organisms to find which tumor is the original tumor. If the original tumor is not one of those biopsied, it will tell you where the cancer originated within the body. You can thus track the progression of cancer throughout a person’s body. Expanding on this, one can even track the effect of cancer through its effects on how organisms interact within ecosystems, creating its own evolutionary stamp on the environment as its effects radiate throughout the ecosystem.

I’ve talked about cancer at decent length (although I could easily go one for many more pages) because it is less well publicly known than some of the other ways that evolutionary theory helps us out in medicine. The increasing resistance of bacteria and viruses to antibiotics is well known. Antibiotic resistance follows standard evolutionary processes, with the result that antibiotic resistant bacteria are expected to kill 10 million people a year by 2050. People have to get a new flu shot every year because the flu viruses are legion and they evolve rapidly to bypass old vaccinations. If we are to accurately predict how the viruses may adapt and properly prepare vaccines for the coming year, evolutionary theory must be taken into account. Without it, the vaccines are much less likely to be effective. Evolutionary studies have pointed out important changes in the Ebola virus and how those changes are affecting its lethality, which will need to be taken into account for effective treatments. Tracking the origins of viruses, like the avian flu or swine flu, gives us information that will be useful in combating them or even stopping them at their source before they become a problem.

Another place that evolutionary theory comes into play is genetically modified organisms. I won’t get into the arguments about whether or not they are safe to eat, other than to say that there is very little evidence to indicate GMO food is any more dangerous than normal food (i.e., yes, there are certain dangers, but nothing that you won’t find in regular, non-GMO food). There are two things about GMOs that I do want to discuss here. First is the belief that GMOs are somehow altogether different from natural organisms. In truth, DNA is swapped between unrelated organisms all the time. Horizontal gene transfer, such as this DNA swapping is known, has been well known in bacteria for over a hundred years. In the past few decades, it has also been found throughout the plant kingdom and even (what people like to call) higher order animals. It has been estimated that as much as 8% of human DNA comes originally from viruses that made their way into our cells, some of which allowed the evolution of the placenta. We even have bacterial DNA in us.

(a) Red aphids get their color from red carotenoid pigment. Genes necessary to make this pigment are present in certain fungi. Scientists speculate that aphids acquired these genes through HGT after consuming fungi for food. If genes for making carotenoids are inactivated by mutation, the aphids revert back to (b) their green color.

http://www.boundless.com/biology/textbooks/boundless-biology-textbook/phylogenies-and-the-history-of-life-20/perspectives-on-the-phylogenetic-tree-135/horizontal-gene-transfer-545-11754/

GMOs also may have an effect on natural ecosystems. They can and do occasionally escape into the wild. Genes from the GMO oilseed rape plant that provide herbicide resistance has spread into wild mustard plants. These plants have spread quite far. Herbicide resistant weeds are springing up all over the world, to the detriment of our farmers and food supply. What was once only a concern for agriculturists is now a concern for anyone concerned about conservation of natural ecosystems. How much of an effect? Unless you understand how evolutionary changes can spread through an ecosystem and what ramifications that may have, you are simply guessing, which is of no use to anyone. People often think of this as a genetics problem or an ecology problem, but this is the effects of evolution at the ecosystem level.

The problems we see in GMOs are not really related to the fact that they are GMO, as evidenced by the natural horizontal gene transfer we see. We see similar problems with no GMOs involved. Pests becoming resistant to pesticides after generations (of the pest) of exposure is a common issue farmers need to address. Weeds will become resistant to herbicides on their own, with no help from GMOs needed. Evolutionary theory will help deal with this problem, guiding us to solutions we may never have reached otherwise.

Another highly controversial topic these days is climate change. Whether we caused it or not is really beside the point and is not a topic we will discuss here. It is undeniable by a quick glance at the evidence that the earth is getting warmer. We will have to deal with it, and so will every other living thing on the planet. Organisms respond to climate change in one of three ways: adapt, move, or die. There are numerous accounts of animals and plants shifting ranges in response to climate change. This is most easily seen in highly mobile organisms. Plants are not generally considered mobile, but pollen and many seeds have huge dispersal potential, so some plants can spread surprisingly quickly. The difference in dispersal ability is a big factor in how the plant communities adapt to climate change. This is not biological evolution in the strict sense of the word. However, over time, these shifts will cause evolutionary change as the population spatial patterns are disrupted.

Unfortunately for many animals and plants, humans have so sliced up the land that mobility is limited (for others, it is greatly expanded, but that is chiefly for things we don’t want to expand, like fire ants or zebra mussels and numerous other invasive species). For these organisms, they have the options of adapt or die. Obviously, this isn’t a conscious choice they make, but conscious or not, these are the options available to them. For these, if we want to know how they will respond to climate change, we need to know their evolutionary potential, what is their ability to adapt and how fast can they adapt. This will depend (assuming similar selective pressures based on climate change) in large part on the genetic variation within the species, their generation rate (the shorter the time between birth and reproduction, the faster evolution can function), and population size. As a result, their conservation depends on our understanding of their evolutionary potential.

Not a good candidate for evolutionary adaptation to climate change. http://inhabitat.com/evolution-cant-keep-pace-with-climate-change/

A critical component here is time. It can be hard to tell whether or not evolution is occurring or more simple phenotypic plasticity (the ability of an organism to respond to changes via changes in gene expression rather than actual genetic change) without substantial genetic study. If an organism has a high phenotypic plasticity, they will be able to adapt quickly. However, if it requires real evolution in the strict sense, that takes time, meaning they will be less likely to adapt in time to prevent extinction. Again, this is a question that can only be answered by proper application of evolutionary principles.

These are just a few examples of how scientists are using evolutionary theory to save lives by improving medical treatments and protect our food supply and environment. I did not provide much in the way of specific examples of these processes, as that would expand this essay far beyond comfortable reading times. However, the links throughout the essay will lead to you several specific examples. Some people may argue that these examples are all microevolution and adaptation, not true macroevolution. In truth, there is no significant difference between the two. Microevolution and adaptation are simply subsets of a larger concept, processes that cause macroevolution over longer time frames.

More importantly, the argument doesn’t matter anyway. It is not important that doctors and farmers know the evolutionary history of earth. The application of evolutionary theory is the same whether one is looking at the present or eons in the past. One can incorporate evolutionary thinking and utilize the theory without ever having to deal with things that are millions of years old, but only if one understands the theory in the first place. Evolutionary theory touches on so many aspects of our lives that if we want to be able to make good decisions on many of the most pressing issues of our time, we need to have some basic understanding of how evolution works. If we do not teach evolutionary theory to our kids, we are crippling our future doctors, farmers, conservationists, fish and game managers, coastal development planners, lawmakers,…

Fossil Friday. Soak up some information

Were you able to guess what the image was? It is a common animal almost everyone has at least a synthetic version of in their home. Yet they make terrible fossils.

Yes, this is a sponge. It is a small one, but typical for a fossil of a sponge. If they preserve well, they look like little balls, or pancakes (the squished ball sponge), or cylinders. All in all, visually very simple.

“Porifera body structures 01” by Philcha – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons – http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Porifera_body_structures_01.png#mediaviewer/File:Porifera_body_structures_01.png

Sponges belong to the the group called Porifera, so named because they have a lot of pores through which water flows through. Even though they may superficially look like some colonial organisms, they are true multicellular animals. Sponges have no true organs, or even tissues, but they do have specialized cells to handle various functions, such as reproduction, producing the materials needed for growing, and cells that act as a primitive immune system. The body organization is about as simple as you can get. Water flows through the pores into a central chamber, which has an opening at the top for water to flow out. As the water flows through, the sponge cells filter out nutrients, generally consisting of bacteria, plankton, and the occasional small animal, and excrete waste products.

Traditionally, sponges have been considered the most primitive of metozoans, the group comprising multicellular animals. There has been some research indicating that comb jellies are more primitive, but that work has been disputed by new research.

“92 ANM Glass sponge 2” by Randolph Femmer – National Biological Information Infrastructure 6259. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons – http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:92_ANM_Glass_sponge_2.jpg#mediaviewer/File:92_ANM_Glass_sponge_2.jpg

Sponges are normally divided into three different types. Demospongia is the largest of the three (although this may be because it includes sponges that may not be as closely related as typically thought). They form a “skeleton” out of small, pointed cylinders called spicules, made from either silica or a protein called “spongin”. The glass sponges, or Hexactinellid sponges, also make silica spicules, but these spicules are noticeably different from the demosponges. The third group of sponges make their spicules out of calcium carbonate and so are known as calcareous sponges. For more information on sponges, the wikipedia article is surprisingly good, so I will not belabor the points here.

It is these spicules that make fossils of sponges so problematic. When the sponges die, the soft tissues decay away and the spicules become little more than sand. Finding an intact fossil sponge is relatively rare. Thus, the vast majority of research done on fossil sponges is done through painstaking microscopic work on the spicules.

The fossil record of sponges goes back possibly as far back as 750 million years, although they do not become common until about 540 million years in the Cambrian and have been found all over the world. In Arkansas, the record of sponges is rather poor, mostly because very few people have worked on them and no one is looking for them. There are currently only four named fossil sponges and a few indeterminate sponge spicules.

Boring sponge, Cliona swpp. Photograph Forest Rohwer, San Diego State University. http://www.sms.si.edu/irlspec/Cliona_spp.htm

Demospongia is represented by three species. Haplistion sphaericum and Virgaspongia ichnata are demosponges found in the Bloyd Formation in Washington County. The Bloyd Formation is a Pennsylvanian aged formation found in the Ozark Mountains, a fossiliferous unit consisting of silty shale to massive sandstones, representing a relatively shallow marine environment with fluctuating sediment influx. Cliona, is a Late Cretaceous demosponge found in the Arkadelphia marl Formation in Hempstead County. Cliona is known as a boring sponge, not because it is uninteresting, but because it has a habit of boring holes into shells. This formation is mostly a limey mud best known for its mosasaurs, but also has a diverse assemblage of marine fossils. Stioderma hadra is the long glass sponge known from Arkansas and was also found in the Bloyd Formation.

The First Mystery Monday of 2015

Time for the first mystery fossil for the year. Can you figure out what this humble little sphere is? Specimens of these little fellows have been around for over 500 million years, but I bet you have a reasonable facsimile in your house.

Leave your thoughts in the comments section and come back Friday for the answer.

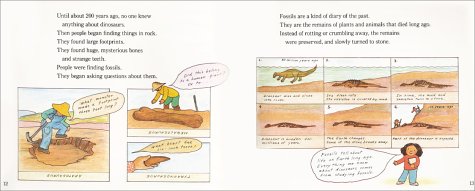

Dinosaurs by Aliki, Part 2

Last post, I reviewed two books by Aliki Brandenberg, called Fossils Tell of Long Ago and Dinosaur Bones. They mostly got good ratings, despite being 25 or more years old. They are still better than many books that are much more current. This time I will look at two more, Digging Up Dinosaurs and Dinosaurs are Different. These books are even older, but Digging Up Dinosaurs continues to be a favorite book by many, despite its age.

Digging Up Dinosaurs

Publication Date: 1981, 1988

Harper Collins Publishers. ISBN: 0-690-04714-2, 0-06-445078-3 (pbk)

AR Book Level: 3.6

This book covers much the same ground as the first two books, but focuses on the path from living dinosaur to being on display in a museum. Appropriately then, the book starts with her in a museum looking at Apatosaurus, or as she states, once known as Brontosaurus. She also looks at a few other dinosaur skeletons, which are mostly drawn reasonably well, although the Tyrannosaurus rex is in the old and inaccurate Godzilla pose.

The next page briefly discusses dinosaurs in general. Sadly, this page does not hold up well, despite its generality. The dinosaurs are drawn in old, toy-like fashion that would not have been considered accurate in the 1980s, much less now. This book suffers the most from inaccurate and simplistic drawings. The dinosaurs are drawn with “bunny hands”, in upright poses dragging their tails, and featherless, along with other problems, such as the giant sauropods having their noses on top of their heads. Even during the 1980s, the drawings were somewhat anachronistic. Now, they are woefully out of date. For a good description of the changes that have gone on in dinosaur art based on new science, check out this article by Darren Naish.

Other problems this page has is the description of some dinosaurs being as small as birds. Yes, because birds are dinosaurs. That was known then, but was not as widely accepted as it is now. So the statement “there hasn’t been a dinosaur around for 65 million years” is not accurate. We also have a much better, if not completely understood, idea of why they became extinct.

The next part of the book talks about people finding fossils and a bit of early dinosaur paleontology history. There is a good, dynamic description of what fossils are and how they form. One complaint here is that paleontology is limited to the study of the fossils, a problem that runs throughout the book. The book does discuss many different jobs needed to collect fossils, but they all focus on collecting, preparing, and studying the fossils. If that were true, we would know very little indeed. Fortunately, study by people throughout the sciences, especially the study of modern organisms, help inform us about dinosaurs and tell us much more than the bones ever could by themselves.

The book continues with a description of finding fossils, what it takes to collect them, and get them back to the museum. Most fossils don’t actually go to museums, but the emphasis here is on the fossils that people see in museums, so we can skip over that detail. These pages illustrate a lot of the back-breaking work involved in digging up a dinosaur. The book also illustrates some of the problems that must be carefully considered during the process, such as getting fragile fossils out of the rock and shipping them to the museum without further damage, and some of the ways those problems are solved.

Once at the museum, there is much work studying the fossils to figure out what they are, which is displayed mostly by scientists looking at a fossil and proclaiming what it is. Sadly, that is exactly what a lot of people think, ignoring the hard work and real science that goes on before any proclamations are made and they are rarely made so definitively as presented. To be fair, the text explains more of the process and makes it much less like arrogant scientists making guesses. The illustrations do not do the words justice.

Photo by Kyle Davies. Baby Apatosaurus bone cast made at the Sam Noble Museum. http://samnoblemuseum.tumblr.com/post/45998762660/how-to-build-a-baby-apatosaurus

The book ends with noting that molds are made from the bones from the better specimens, so that copies can be made. These fiberglass (or plastic) copies are what is seen on display in most museums, but they look just like the original. This is an important point. Many people assume that if it isn’t the real bone, it is “fake”. Unfortunately, they use fake for both a copy of an original and something that is not real, and they usually confuse the two meanings. To be clear, these copies are NOT fake. They are more appropriately termed replicas. They are not the actual bone, but they look just the same. Because this is such a common mistake, it is great to see the actual process described here.

The other thing shown here, which makes this last part the best part of the entire book, is an illustration of a discussion among some scientists in the background. They are talking about new ideas and discoveries and make the important comment that if the ideas are confirmed, they will have to change their model. Changing what we think in the face of new evidence is the essential ingredient in science. This illustration not only shows the benefits of the fiberglass copies, but it shows real science in action.

Dinosaurs Are Different

Publication Date: 1985

Harper Collins Publishers. ISBN: 0-690-04456-9, 0-06-445056-2 (pbk)

AR Book Level: 3.6

Dinosaurs Are Different introduces the diversity of dinosaurs to kids, breaking up a nebulous, homogeneous concept of “dinosaur” into an array of different types. It does a good job of showing different types of dinosaurs. It also nicely shows pterosaurs as being related to, but not actually being dinosaurs. The book, to its credit, gives a clear and succinct of the characteristics that scientists use to categorize the dinosaurs. So at this level, the book succeeds well. There are some problems in the details, though, because the science has moved on.

The biggest problem this book has, as in the previous book, is the illustrations that show the dinosaurs in a woefully antiquated style. The postures retain the slow, ponderous, tail-dragging poses that were popular before the 70s when we started learning more about dinosaurs. John Ostrom‘s work on Deinonychus began the revival of the idea that birds evolved from dinosaurs and, along with it, the view that dinosaurs were not the slow reptiles of yore, but active, dynamic animals. The more active view really became widely accepted when Jurassic Park hit the movie screens (although Jurassic Park committed the faux-paus of bunny hands and fatherless raptors as well). Since then, even more changes have covered more and more dinosaurs in feathers. As a result, the illustrations look painfully anachronistic. On the plus side, she still draws kids talking about related things and they are well worth reading.

The book starts with a brief discussion of observations on the skeletons that the teeth indicated diet, nicely done for little kids. It then talks about differences in hip structure. This is the chief characteristic separating the two main groups of dinosaurs and she does a great job of explaining the hip types and how they are used to categorize the dinosaurs into saurischians (lizard-hipped) and ornithischians (bird-hipped). She talks about how both dinosaur groups, along with crocodilians, are part of the group called archosaurs, the “ruling reptiles”. So far, so good. I like this discussion because it shows some of the steps scientists really use to figure out relationships in fossils.

But then some problems arise. Thecodonts are described as the ancestors of both groups of dinosaurs, crocodilians and pterosaurs. In the illustration (and text), she properly indicates that pterosaurs are not dinosaurs like they are often shown. However, she makes it appear that the different groups of dinosaurs are no more closely related to each other than they are to pterosaurs and crocodilians. We now know that “thecodonts” did not constitute a real group, meaning that it contained many animals that were not really related to each other and so it is no longer recognized; it holds no place in modern discussions. All archosaurs arose from a small group within what was traditionally called thecodonts and moreover, all share a common ancestor. From that ancestor, the crocodilians split off, then the pterosaurs, leaving the dinosaurs, which only then split into the two groups.

There is a page in here that hits a particular sore point with me. It is a discussion between a boy and a girl talking about what dinosaurs are. They talk about dinosaurs being reptiles and then lists several characteristics reptiles have. This is a problem because not all reptiles have these characteristics and because scientifically, animals are generally not defined by superficial characteristics like this. If at all possible, organisms are classified according to their relationships as far as we know them. A platypus lays eggs, but that does not make it a reptile. Many lizards bear live young (there is even a frog that does this), but they are still reptiles. Nevertheless, it continues to be a major challenge getting people to understand this, that organisms can not be properly classified according to what they look like.

The second half of the discussion is much better as it moves into how reptiles are broadly categorized by the type of skull they have. This is a sophisticated point for a book geared to kids and she handles it well, considering her target audience. Sadly, she makes a blunder. She calls synapsids reptiles. When the book was published, it was still common (and sadly, is still such in some circles) to call synapsids “mammal-like reptiles.” There is only one small problem. They weren’t reptiles. Amniotes, animals that lay eggs capable of surviving on land, are split into two main groups: the synapsids and the reptiles (often called Sauropsida because of all the baggage that comes with the term reptile). You may guess by that split that mammals are synapsids and you would be right. Now at the earliest stages, would you have been able to tell them apart? Not really. They both would have looked much like reptiles. But there were important changes that sent them careening off onto very different evolutionary paths.

Moving on, we get to really good parts of the book. The predentary, a bone at the front of the lower jaw, as a characteristic of ornithischians and its relationship with herbivory is well discussed. As the book goes into the saurischians, the differences between the two main groups, the sauropods and theropods are shown well.

Unfortunately, time once again rears its ugly head as progressed marched on. The simplistic definition of coelurosaurs and carnosaurs as little theropods and big theropods, respectively, is completely wrong today. We now know that theropods changed sizes radically several times. It is no longer possible to split them up by size anymore that makes any evolutionary sense. It is also no longer true that all theropods ate meat as we now know some that were herbivores, most notably the therizinosaurs, which admittedly, were not really known when the book was written. It however, can be said that MOST theropods were carnivores.

The relationships within the Ornithischia are now very different than what is described in this book. The book describes four major groups: ornithopods, ceratopsians, stegosaurs, and ankylosaurs. There is a good discussion of hadrosaurs as ornithopods. However, unlike the book states, psittacosaurs and pachycephalosaurs are not ornithopods. Psittacosaurs are considered to be one of the earliest ceratopsians, the lineage that includes Triceratops. Pachycephalosaurs, the bone-headed dinosaurs, are also placed in a group with ceratopsians called marginocephalians. Ornithopods are are completely separate group of ornithischians. Stegosaurs and ankylosaurs are also now thought to be more closely related to each other than to the rest of the Ornithischians. New fossils have also told us how the plates on Stegosaurus were positioned (up in two rows). We also have a much better understanding for why they had them, which applies to all the rest of the groups as well. The numerous and fancy head ornaments, plates, and spikes were most likely primarily as sexual displays. They may have had secondary uses in defense, offense, or cooling, but they were primarily display structures.

The last page is a list of the different types of dinosaurs and their diet. Time and new discoveries has made this list far more diverse than Aliki could have imagined 30 years ago.

In conclusion, would I recommend the books? Yes, despite their flaws. They cover several concepts well. Digging Up Dinosaurs holds up a bit better, but both suffer from outmoded drawings and advances in our understandings of dinosaur relationships. But these flaws, if recognized, can be usefully used as valuable teaching moments to talk about how science is a dynamic field, how what we know is constantly being reevaluated based on new evidence, helping us to test and refine our ideas. Comparing the book to a more modern book would make an interesting and informative educational experience.

Happy New Year!

Happy New Year and welcome to 2015! I know it is after January 1st, but this is the first workday of the new year for many people. It is the time that we are putting aside holiday treats and adding to our productivity rather than our waistlines. Paleoaerie is returning after the holidays to supply more dinosaur and evolution fun facts and educational materials.

This is just a short post to get things rolling for the new year. The next post later this week will have the second half of the Aliki books. Next week will kick off another round of Mystery Monday fossils. After that, there will be many a topic to discuss. If you have anything in particular you would like to have discussed or would like to contribute as a post, please feel free to let me know. let’s make this year one of increased collaboration and sharing, exponentially increasing the fun and learning.