Home » Paleontology » Fossils of Arkansas (Page 6)

Category Archives: Fossils of Arkansas

National Fossil Day Approaches

National Fossil Day is October 15th, but the Museum of Discovery, in conjunction with the Earth Science and Anthropology departments at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock (UALR), the Arkansas Geological Survey, the Arkansas State University Museum, the Virtual Fossil Museum, and others (including of course, me) will be putting on an exhibit on October 11th. If you are in the neighborhood, please stop in. there is much to do and see for everyone from toddlers to grandparents and professional researchers.

National Fossil Day is October 15th, but the Museum of Discovery, in conjunction with the Earth Science and Anthropology departments at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock (UALR), the Arkansas Geological Survey, the Arkansas State University Museum, the Virtual Fossil Museum, and others (including of course, me) will be putting on an exhibit on October 11th. If you are in the neighborhood, please stop in. there is much to do and see for everyone from toddlers to grandparents and professional researchers.

This week I will be sharing a few photos of the collections at the UALR Earth Science Department as a preview of things you will see. We will start with echinoderms today. These include crinoids, sea urchins, starfish, and an array of others.

Fossil Friday, Stepping into the Weekend

So were you able to figure out what Monday’s fossil was? Congratulations to Herman Diaz for not only correctly identifying it, but the relative that lived in Arkansas as well. If you want to see it in person, along with much more, come out to the National Fossil Day event at the Museum of Discovery in Little Rock.

This is the foot of Allosaurus fragilis, which means “different delicate reptile”. It has gone by a lot of names. Depending on the researcher you ask, Antrodemus, Creosaurus, Labrosaurus, Epanterias, and Saurophaganax are all just versions of Allosaurus.

This is the foot of Allosaurus fragilis, which means “different delicate reptile”. It has gone by a lot of names. Depending on the researcher you ask, Antrodemus, Creosaurus, Labrosaurus, Epanterias, and Saurophaganax are all just versions of Allosaurus.

Because of this, it can be difficult to say just how big Allosaurus was. The most famous specimen called “Big Al” is actually on the small side, measuring only about 7.5 m (25 ft), whereas the American Museum of Natural History has a specimen that is almost 10 m (33 ft.). The fossil called Epanterias is a good 12 m (40 ft.). Thus, Allosaurus may have been essentially the same length as Tyrannosaurus rex, although it was more lightly built, so it would not have weighed as much. We should keep in mind though, that every species has a fairly wide range of sizes, so even when we can measure a bunch of living specimens, stating an average size has to come with wide error bars, so take these measurements with a grain of salt.

Allosaurus itself never lived in Arkansas. But a close relative of it did. Acrocanthosaurus is classified as a Carcharodontosaurid, which is a group that is generally considered to by descended from earlier allosaurs. Allosaurus himself lived in the late Jurassic Period, whereas Acrocanthosaurus lived in the early to middle Cretaceous, so the timing lines up with what we know. No bones of Acrocanthosaurus have ever been found in Arkansas, although they have been found in Texas and Oklahoma. What we do have in Arkansas is their tracks. A large trackway was found in Howard County in 2011. This trackway was mostly footprints of large sauropods such as Sauroposeidon, but it also contained theropod trackways, which were identified as being from Acrocanthosaurus.

Acrocanthosaurus was as big as the biggest allosaurs and was known for unusually long spines on the vertebra, especially over the ribcage. Why did it have the spines? While they weren’t as tall as Spinosaurus, but they were longer than would be necessary for strictly muscle attachment, so the best explanation was that it formed part of a display to make it look bigger and more impressive. It was the biggest predator around, so it likely was not for defense, but to intimidate rivals and impress potential mates.

As the biggest predator around, it preyed upon the main herbivores of the day, which in this case were probably juvenile or elderly sauropods (the healthy adults were likely immune from predation simply on account of size). The skulls were more lightly built than tyrannosaurs, so they probably did not munch through bone like tyrannosaurs. They were apparently more selective in their eating. This would have made them very popular with the scavengers of the time as they would have left more behind.

Stepping into a Belated Fossil Friday

Were you able to figure out what last Monday’s fossil was? It is on display at Mid-America Museum in Hot Springs, AR. Ordinarily this would have been posted last Friday, but real life intervened. Apologies for that. Part of what happened was that when I posted the original picture last Monday, I thought I understood the background behind the fossil. It turns out that new research was published in 2013 that changed a lot of the more detailed interpretations. It didn’t change anything of importance to anyone not obsessed with details, but it sent me on a three day search for answers.

What we are looking at here is a foot print of a sauropod. Sauropods were herbivorous, long-necked dinosaurs and were the biggest animals to ever walk the earth, some of them possibly massing 50-80 tons and stretching well over 30 m (100 feet). We can’t say exactly which one made this particular footprint, but we can take a pretty good guess. If you guessed Sauroposeidon, or Astrodon, or Pleurocoelus, or Paluxysaurus, or Astrophocaudia, or Cedarosaurus, you are at least partially correct. These are all titanosaurs, a subgroup of sauropods. But which one we call it is more problematic. It is usually almost impossible to tell exactly which species made a particular track and in this case, it gets even harder because there isn’t a lot of agreement over which names are even valid.

Before we get into that morass, what is a titanosaur anyway? Titanosaurs have been in the news recently with the discovery of Dreadnoughtus. Most people are familiar with Diplodocus and Brachiosaurus, the two iconic sauropods. These two dinosaurs are the best known representatives of the two main groups of sauropods, with many species in each group. Diplodocus had shorter front legs than back legs and was relatively thin with a long, whip-like tail. It’s head was small and elongate, with simple, peg-like teeth in the front of the jaws. Brachiosaurus had longer legs in front than in back and was stockier, with a shorter, stubbier tail. It’s head was larger, with spoon-shaped teeth. Titanosaurs had front legs that were roughly the same length as the back legs, with a relatively whip-like tail like Diplodocus, although not thought to be as long. The heads looked like Brachiosaurus, but more elongate. Some had teeth like Diplodocus, some like Brachiosaurus. Basically, if you try to envision an intermediate form between Brachiosaurus and Diplodocus, you would wind up with something that looked like a titanosaur, which is rather interesting because all the studies trying to figure out their relationships place titanosaurs as much more closely related to brachiosaurs than to diplodocids. In fact, titanosaurs likely evolved from early brachiosaurids, which means that all the characteristics that make them look sort of like diplodocids are examples of convergent evolution, if the hypotheses about their relationships are correct.

Before we get into that morass, what is a titanosaur anyway? Titanosaurs have been in the news recently with the discovery of Dreadnoughtus. Most people are familiar with Diplodocus and Brachiosaurus, the two iconic sauropods. These two dinosaurs are the best known representatives of the two main groups of sauropods, with many species in each group. Diplodocus had shorter front legs than back legs and was relatively thin with a long, whip-like tail. It’s head was small and elongate, with simple, peg-like teeth in the front of the jaws. Brachiosaurus had longer legs in front than in back and was stockier, with a shorter, stubbier tail. It’s head was larger, with spoon-shaped teeth. Titanosaurs had front legs that were roughly the same length as the back legs, with a relatively whip-like tail like Diplodocus, although not thought to be as long. The heads looked like Brachiosaurus, but more elongate. Some had teeth like Diplodocus, some like Brachiosaurus. Basically, if you try to envision an intermediate form between Brachiosaurus and Diplodocus, you would wind up with something that looked like a titanosaur, which is rather interesting because all the studies trying to figure out their relationships place titanosaurs as much more closely related to brachiosaurs than to diplodocids. In fact, titanosaurs likely evolved from early brachiosaurids, which means that all the characteristics that make them look sort of like diplodocids are examples of convergent evolution, if the hypotheses about their relationships are correct.

What’s in a name?

Now that we know basically what we are looking at, what do we call the one which may have made this track? That is an excellent question. Two different trackways have been found in Arkansas, both in a commercial quarry in Howard County. They were fantastic finds, with thousands of tracks (5-10,000 tracks in the first trackway alone), placing them among the biggest dinosaur trackways ever found. Unfortunately, other than a few tracks that were spared, they no longer exist as they were destroyed by the quarry operations. That is a sad loss for paleontology, but in defense of the quarry owners, the tracks were found on private land and the owners had no legal requirement to tell anyone about them at all, they are running a business after all. They allowed scientists to study the trackways and in the case of the second trackway, they approached scientists at the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville about the tracks on their own initiative, giving them the opportunity to study the tracks before they were destroyed. As a result, careful maps were drawn, some tracks were removed and others were saved as casts. So the trackways themselves may be gone, but the knowledge of them is still with us and in the public domain.

The tracks were initially described as being from either Astrodon or Pleurocoelus, based on the fact that fossils from these dinosaurs have been identified in Oklahoma in rock units called the Antlers Formation, which is correlated with the Trinity Formation in southwest Arkansas. However, some researchers have concluded that the material upon which these names are based can not be reliably distinguished from any other titanosaur, so the names are what is called nomen dubium, literally dubious names. Pleuocoelus became what is commonly referred to as a junk taxon, which are used as a waste basket for material not identifiable as something else. In this case, when people found bits of a titanosaur in the southern United States they couldn’t identify, they said, it’s um…uh…Pleurocoelus? Pleurocoelus! Yeah! That’s the ticket! In 2013, Michael D’Emic published his research in which he found that part of the material identified as Pleurocoelus are really from two different sauropods called Cedarosaurus and Astrocaudia, and other parts are from a Texan sauropod called Paluxysaurus, leaving other bits unidentifiable as anything other than indeterminant titanosaur. Additionally, he found that Paluxysaurus was simply a juvenile form of Sauroposeidon, a giant sauropod known from four huge cervical (neck) vertebrae found in Oklahoma. So in conclusion, what can we say about the tracks? They were made by a titanosaurid sauropod.

Life’s a Beach

The first trackway was found by Jeff Pittman in 1983 while he was working in the quarry for his master’s degree at Southern Methodist University (SMU). The second set was found in 2011 by quarry workers, who brought it to the attention of Stephen Boss, a geologist at the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville. The tracks in the first trackway were 12-24″ across and were interpreted as being from from adult sauropods. The other trackway was more diverse, with tridactyl (three-toed) footprints attributed to the giant carnivorous dinosaur Acrocanthosaurus, as well as tetradactyl (four-toed) tracks which may have been made by a crocodilian of some sort. The pictures below are of the first trackway, taken by David Gillette, and can be found at his site discussing Seismosaurus.

The rocks in which both of the trackways were found is in what is called the DeQueen Limestone, a subunit of the Trinity Formation. These rocks were laid down in the Early Cretaceous about 115 to 120 million years ago. At the time, the shore of the Gulf Coast went through Arkansas, so much of southwest Arkansas was underwater. The DeQueen Limestome has thin layers of sandy limestone, many of which are quite fossiliferous, with oyster shells in abundance. There are also layers of limy clay and gypsum, indicating the air was fairly hot and dry. Stephen Boss likens the environment at the time to be similar to the Persian Gulf of today. So what we have is the coast of a very warm shallow sea. The dinosaurs appear to have been using the area as part of a migratory pathway. So while no bones of these dinosaurs have been found in Arkansas yet, we know they were here, so keep an eye out when you are fossil-hunting in southwest Arkansas. Who knows, you might find something bigger than you imagine.

Depiction of the environment during the formation of the trackway. Mark Hallett. http://www.columbia.edu/dlc/cup/gillette/gillette19.html

Fossil Friday, Going Swimmingly

No one guessed what the fossil for this week was. Take a look at the image below and see if you can figure out who this vertebra belongs to before continuing on after the image. As you may have deduced from the title of the post, it is an aquatic animal.

This fossil is a really nice dorsal vertebra of a giant marine reptile. Most of the ones usually found in Arkansas are mosasaurs, but this one is different. It lived at the same time as the mosasaurs, placing it in the Late Cretaceous Period. As with all other Late Cretaceous fossils in Arkansas, it was found in the southwest corner. Specifically, it was found near Saratoga, Arkansas in Howard County by local resident Matt Smith. Interestingly, the very same spot has also turned up several nice mosasaur fossils, so it was a popular place in the Cretaceous seas. It shouldn’t be too surprising though, as it was a nearshore environment in a tropical climate much like the Bahamas today, so there would have been lots of good eating for hungry marine predators.

Ok, enough of the teasing. The vertebra we have here is that of a plesiosaur known as Elasmosaurus. These are classic marine reptiles that most people are familiar with to some degree. They have sometimes been described as looking like a snake that swallowed a sea turtle because of the relatively wide bodies with oar-like flippers and a very long neck. They are thought to have spent much of their time slowly cruising the seaways, using their long necks to catch fish unawares. some people have even suggestd that they floated at the surface of the water with their head out of the water, so that fish could not see it, allowing them to plunge their head down into the water and catch fish from above. That is pure speculation though. Right now there is no way to really test such hypotheses, so feeding methods remain in the realm of speculation until such time as someone figures out a way to test it adequately. At the moment, biomechanical tests indicate that either method would have been possible.

So if you find a vertebra like this, how do you tell whether it is a mosasaur or plesiosaur vertebra? They can both be large, although the one pictured here is the largest one I have ever seen found in Arkansas. The best way to tell is to look at the ends of the centrum, otherwise known as the body of the vertebra. Most of the time, that is all that is preserved, as all the processes that stick out have been broken off, like we see in this one. Plesiosaur vertebra have flat, possibly even slightly concave, or indented ends. Mosasaurs, on the other hand, have what is known as procoelous vertebrae, which have one end convex, a bit more rounded off. These differences make mosasaur vertebrae look more like over-sized lizard or croc vertebrae, whereas plesiosaur vertebebrae look more like the disc-like vertebrae seen in fish. This may mean that plesiosaurs were more adapted for aquatic life than mosasaurs. Both were clearly fully aquatic, what with neithr one of them having legs of any sort, but plesiosaurs appear to have been aquatic for longer, giving their spine to more fully adapt.

Indeed, when we look at the age of the rocks their fossils have been found, mosasaurs are restricted to the late Cretaceous, whereas the plesiosaurs first appeared all the way back in the Triassic (another successful prediction based on evolutionary theory). This means plesiosaurs had well over 100 million years advance on the mosasaurs. It didn’t really help them in the end though. About the time mosasaurs appeared, plesiosaurs were declining. Mosasaurs evolved and spread quickly, becoming the dominant marine predator of the Latest Cretaceous. Does this mean that mosasaurs outcompeted the plesiosaurs? Not necessarily. It has not yet been sufficiently determined whether or not mosasaurs simply filled a niche left open by the plesiosaur decline or competitively excluded them. there is also the argument to be made that they would not have competed at all. The body shapes of mosasaurs and plesiosaurs are quite different, indicating they filled different niches in the marine realm, so they weren’t going after the same food sources. Therefore, there is no particular reason we know of that they could not have existed alongside each other without adversely affecting each other.

Most people are familiar with them due to the much discussed “Loch Ness Monster”, which has often been said to be a supposed plesiosaur that has somehow survived for 70 million years. Of course, that idea doesn’t make a lot of sense for several reasons. It is highly unlikely that plesiosaurs could have lived for so long without leaving any trace of a fossil record. It does happen occasionally though. The coelacanth is a famous example of that, for a long time having a good 65 million year gap in their fossil record. They were thought to have gone extinct along with the dinosaurs until living specimens were caught. We know more about them now and their fossil record is no longer quite as limited as it once was, but it still has wide gaps in the fossil record. But more serious problems for Nessie arise from the fact that plesiosaurs were large, air-breathing marine reptiles. Coelacanths went unnoticed because they moved to the bottom of the sea, an option not available to plesiosaurs, which were limited to surface waters, and relatively shallow waters at that. That means they lived in exactly the sort of marine environments most visited by humans. That makes it hard for them to hide from people today and puts their bones in prime spots in the past to fossilize. Then of course, there is the problem that Loch Ness is a freshwater lake and plesiosaurs were adapted for saltwater. Not to say a species couldn’t have adapted for freshwater, but it does make it less likely. Finally, there would have to be enough plesiosaurs big enough to support a breeding population and there is simply no way they could all hide within the confines of a lake, especially since they have to live at the surface much of the time.

But what about the supposed bodies that have been found of plesiosaurs? They have all been identified as decomposing backing sharks. Basking sharks are one of the largest sharks known today. they are pretty harmless though, as they are filter feeders, much like the whale shark. When their bodies decompose, the jaws typically fall off pretty quickly. So what has been identified as the head of a “plesiosaur” was actually just the remaining portions of the cartilaginous skull without the large jaws. If you look at the picture of the asking shark here, there isn’t much left after you remove the jaws.

But what about the supposed bodies that have been found of plesiosaurs? They have all been identified as decomposing backing sharks. Basking sharks are one of the largest sharks known today. they are pretty harmless though, as they are filter feeders, much like the whale shark. When their bodies decompose, the jaws typically fall off pretty quickly. So what has been identified as the head of a “plesiosaur” was actually just the remaining portions of the cartilaginous skull without the large jaws. If you look at the picture of the asking shark here, there isn’t much left after you remove the jaws.

Next week is Labor Day on Monday, so I will likely not post a new fossil next week. I will post something next week, just not a mystery fossil. But there will definitely be one the following week, so please come back to see the next fossil and see if you can guess what it is before Friday. In the meantime, enjoy your vacation.

Mystery Monday Returns

Welcome back! the new school year has started for most, if not all, people by now. Everyone is busily trying to figure out new schedules, new curricula, new people, sometimes even new schools. Changes are everywhere this time of year. Paleoaerie is no exception. We didn’t get quite as much done over the summer as we would have liked (does anyone?), but it was an interesting summer, filled with good and bad. To start with the bad, the UALR web design course that was initially going to work on revamping the website is no more due to unexpected shakeups at the school. Nevertheless, a different course will take a look at the site and see what they can do, although they sadly won’t have as much time to deal with it.

But there was a lot of good that happened. Big news for Paleoaerie is that we are now partnered with the Arkansas STEM Coalition, a nonprofit advocacy group for STEM education within Arkansas. This is really important for us because this means Paleoaerie now operates as an official nonprofit organization. What does this mean for us and you? It means that any donation to the site is tax-deductible. It also means that many grants that we could not apply for before are now within possible reach. Fundraising should be a bit easier from now on, which means we may be able to do much more in the upcoming future. One of the things we will be doing in the near future is a Kickstarter campaign to buy a 3D laser scanner so that we can start adding 3D images of Arkansas fossils onto the website, which will be available for anyone to use. One might ask why not use some of the cheap or even free photographic methods that are available. In a word: resolution. I’ve tried other methods. When one is attempting to make a 3D image of an intricate object only a few centimeters across, they don’t work well. If you want details to show up, you need a better system. Stay tuned for that.

But there was a lot of good that happened. Big news for Paleoaerie is that we are now partnered with the Arkansas STEM Coalition, a nonprofit advocacy group for STEM education within Arkansas. This is really important for us because this means Paleoaerie now operates as an official nonprofit organization. What does this mean for us and you? It means that any donation to the site is tax-deductible. It also means that many grants that we could not apply for before are now within possible reach. Fundraising should be a bit easier from now on, which means we may be able to do much more in the upcoming future. One of the things we will be doing in the near future is a Kickstarter campaign to buy a 3D laser scanner so that we can start adding 3D images of Arkansas fossils onto the website, which will be available for anyone to use. One might ask why not use some of the cheap or even free photographic methods that are available. In a word: resolution. I’ve tried other methods. When one is attempting to make a 3D image of an intricate object only a few centimeters across, they don’t work well. If you want details to show up, you need a better system. Stay tuned for that.

Paleoaerie is also partnering with the Museum of Discovery and the University of Arkansas at Little Rock for a National Fossil Day event on October 11. Make sure to mark your calendars and come out to the museum to see the spectacle and diversity that can be found in Arkansas. There is much more than you think. We are also working with the museum on a new dinosaur traveling exhibit. It is very cool, so watch for it later this fall.

Paleoaerie is also partnering with the Museum of Discovery and the University of Arkansas at Little Rock for a National Fossil Day event on October 11. Make sure to mark your calendars and come out to the museum to see the spectacle and diversity that can be found in Arkansas. There is much more than you think. We are also working with the museum on a new dinosaur traveling exhibit. It is very cool, so watch for it later this fall.

The last big news that happened recently is today’s Mystery Monday fossil. Someone brought me a fossil to examine a couple of weeks ago. The first amazing part of it is that is was actually a fossil. the vast majority of what people show me are just interestingly shaped rocks. This was a bona fide fossil. Not only was it a fossil, but a really cool one. The image below is a vertebra from a little seen animal in Arkansas and not at all for a very long time. The fossil is roughly 100 million years old, putting it in the Cretaceous Period. At that time, Arkansas was on the shoreline of the late Cretaceous Interior Seaway. Take a look at the image below and see if you can figure out what it came from. I’ll let you know what it is Friday. Thanks to Matt Smith for bringing this wonderful fossil to my attention. Come out to the National Fossil Day event and see it for yourself.

Taphonomy Tuesday

Taphonomy Tuesday? What the heck is taphonomy, you ask? Taphonomy is the study of burial processes and all the changes that take place betwixt death and being collected as a fossil. One might also include the effect of sexiness in what fossils get studied and forgotten about, way more people are interested in tyrannosaurs than fossil mosquitos, for instance. Change comes to all things and paleoaerie is no exception. You may have noticed that the answer to Monday’s mystery fossil did not get posted on the blog last week, although it was posted on the Facebook page. That will be rectified today. But first, a couple of pieces of news.

Taphonomy Tuesday? What the heck is taphonomy, you ask? Taphonomy is the study of burial processes and all the changes that take place betwixt death and being collected as a fossil. One might also include the effect of sexiness in what fossils get studied and forgotten about, way more people are interested in tyrannosaurs than fossil mosquitos, for instance. Change comes to all things and paleoaerie is no exception. You may have noticed that the answer to Monday’s mystery fossil did not get posted on the blog last week, although it was posted on the Facebook page. That will be rectified today. But first, a couple of pieces of news.

Mystery Monday and Fossil Friday will be suspended for the summer so I can work on other aspects of the website. I would like to make some different posts and add more to the site. however, for those of you who are primarily interested in the fossils, they will return along with school, teachers, and homework, although hopefully a bit more fun than either doing or, even worse, grading homework (trust me, having been both a student and teacher, grading is almost always more painful than doing the assignments). In the meantime, you can look forward to more varied posts, the addition of a couple of things, such as a techno page for recommended apps and multimedia and an Amazon store in which you can peruse recommended items (and in a small way support the work of paleoaerie, which while free to you, is not to me). So I hope you will stick with me through these Darwinian changes and avoid the pitchforks and torches (ed. note: in keeping with the medieval theme of the picture, I thought about saying burning faggots, but so few people these days know that in olden times, faggot simply meant a bundle of sticks, language too evolves).

The other big news is that I have started a collaboration with the Museum of Discovery in Little Rock to host a celebration of National Fossil Day in October. I am really looking forward to it and, between me and the museum educators at the MoD, we have a lot of ideas for things to do. I hope everyone can come out and enjoy the festivities and learn about fossils in Arkansas and beyond firsthand.

The other big news is that I have started a collaboration with the Museum of Discovery in Little Rock to host a celebration of National Fossil Day in October. I am really looking forward to it and, between me and the museum educators at the MoD, we have a lot of ideas for things to do. I hope everyone can come out and enjoy the festivities and learn about fossils in Arkansas and beyond firsthand.

Now, for that fossil…Did any of you recognize this as the skull of a mosaaur, specifically that of Platecarpus? To picture a mosasaur, imagine a komodo dragon, replace the feet with flippers, and compress the tail so it is taller than it is wide (aka laterally compressed) so it looks more fish-like than lizard-like, and you have a pretty good view of a mosasaur. There is a reason for that. Komodo dragons are part of a group of lizard called monitor lizards, which are thought to be close relatives of mosasaurs and so are likely an excellent model for what the ancestral animal of mosasaurs looked like before they became aquatic.

Platecarpus was a carnivorous marine reptile that swam in the Cretaceous seas. While dinosaurs like Tyrannosaurus rex and Triceratops roamed the land, Platecarpus and its relatives patrolled the oceans. This is one of the most common mosasaurs, so much of what we know about them comes from fossil of this genus. It was smaller than many of the other mosasaurs. Some, like Kronosaurus, could reach up to 17 meters, but Platecarpus only averaged around 4-7 meters. Its name means “flat wrist,” alluding to the flippers, although it hardly distinguishes them from other mosasaurs in this regard. What did make them stand out from the other mosasaurs was a relatively shorter snout with eyes that faced more forward, so it probably had better stereoscopic vision, that is, it had better depth perception than most others of its kind. This may be why it had a shorter snout, to prevent the snout from blocking its field of view. Like other mosasaurs, Platecarpus had two rows of teeth on its palatine bones, forming the roof of its mouth. This arrangement actually isn’t all that unusual in lizards and snakes, it is really common in fish. The teeth (all of them, not just the palatal teeth) were pointed and conical, although not as sharp as some of its kin, indicating it went after small, soft prey, like small fish and soft invertebrates like squid or perhaps even jellyfish. They could have gone after larger prey like crocodilians do, but unlike crocodilians which have a strong skull capable of withstanding the forces of ripping a prey item apart, Platecarpus had a much weaker skull which would likely not have stood up to the stresses of the crocodilian death roll (this is when they grab a limb and spin until the limb is ripped off, the moral of the story is of course, never dance with a gator). The overall shape of Platecarpus is stockier than most mosasaurs. This would have had the effect of decreasing surface area relative to body weight, which could have increased its metabolism by holding in heat better.

KUVP1001. Mike Everhart. http://www.oceansofkansas.com

One of the things that makes Platecarpus as a genus so interesting is the fossils that have been found with soft tissue preservation. In one, along with parts of the skin, parts of the trachea (windpipe) were preserved. Originally, they were interpreted as part of a dorsal fin, thus all the early pictures of mosasaurs with fins along their backs. However, it was quickly discovered what the traces really were. To his credit, Williston, the scientist who had reported in 1899 the traces as a dorsal fins was the one who published another short paper three years later saying he had made a mistake and the fossil really showed the cartilaginous rings found in trachea. The tracheal rings have also been interpreted as showing the branching point between the two lungs, which is important because it answered a question about their origins. Every researcher agrees that mosasaurs are lepidosaurs, the group including lizards and snakes, but what wasn’t known was whether or not mosasaurs were derived from aquatic lizards or from snakes. The discovery of a trachea showing two lungs confirms the origin within lizards (snakes only have one lung). It may still be that snakes evolved from mosasaurs, but that is not very likely.

The other piece of soft tissue that has been found is the outline of the tail showing a lobe on the tail forming a very shark-like tail. Until this time, many people had thought the mosasaur swam with an eel-like motion, but the tail and the deep caudal fins indicate a much faster shark-like swimming motion. This in turn has caused people to reevaluate the view they were slow ambush predators, supporting a more active predatory forager. Whether or not other mosasaurs had this fin is currently unclear, so there may have been specializations within this group not seen in the larger mosasaur family. Another such example is the discovery of what has been interpreted as thicker eardrums, which may have allowed them to dive to deeper depths.

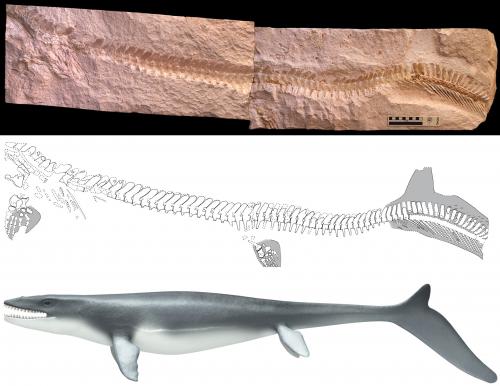

Tail fluke preserved around skeleton. Credit: (top) Photograph (by Johan Lindgren), (centre) sketch indicating the bones and skin structures preserved (by Johan Lindgren), and (bottom) life reconstruction (by Stefan Sølberg) of Prognathodon sp.

The southwestern corner of Arkansas was at the edge of the Late Cretaceous Western Interior Seaway, so we have several fossils of them in places like Clark, Hempstead and Howard counties, although you can find them all over the world in the right type of rocks. You can find them in the Brownstone and Marlbrook Marl Formations. These formations are indicative of warm, shallow seas, much like the Bahamas today, which considering the locations, shouldn’t come as too much of a surprise to people. If you were taking a nice vacation on the warm Cretaceous beaches 80-85 million years ago, you might have tried fleeing into the water to avoid the dinosaurs on the beach, but you would have been no safer in the water.

I would like to thank Rachel Moore, who supplied a lot of the research involved in putting this post together.

Mystery Monday

For today’s Mystery Monday fossil, see if you can identify this creature.

Fossil Friday

It’s Friday, time for the answer to Monday’s mystery fossil. Were you able to identify it?

These fossils are from a fish called Enchodus, the “saber-fanged herring.” Teeth of Enchodus are commonly found in the Cretaceous-aged rocks in southwestern Arkansas, especially near Malvern and Arkadelphia in the Arkadelphia and Marlbrook Marl Formations, up into the Paleocene rocks of the Midway Group a bit farther north. In other places you can even find them in rocks of Eocene age, although you will have much better luck in the Cretaceous rocks. At this time, southern Arkansas was shallow to coastal marine. Go to the Bahamas, imagine Enchodus, mosasaurs, plesiosaurs, and plenty of sharks in the water around the islands and you would have a good picture of the landscape back then. They were abundant at the end of the Mesozoic Era and survived the asteroid impact that rang the death knell for many animals, including the non-avian dinosaurs. But they never regained their prominence as a key member of the marine ecosystem, eventually dying out completely in the Eocene sometime around 40 million years ago (the Eocene lasted from 55 to 34 million years ago).

These fossils are from a fish called Enchodus, the “saber-fanged herring.” Teeth of Enchodus are commonly found in the Cretaceous-aged rocks in southwestern Arkansas, especially near Malvern and Arkadelphia in the Arkadelphia and Marlbrook Marl Formations, up into the Paleocene rocks of the Midway Group a bit farther north. In other places you can even find them in rocks of Eocene age, although you will have much better luck in the Cretaceous rocks. At this time, southern Arkansas was shallow to coastal marine. Go to the Bahamas, imagine Enchodus, mosasaurs, plesiosaurs, and plenty of sharks in the water around the islands and you would have a good picture of the landscape back then. They were abundant at the end of the Mesozoic Era and survived the asteroid impact that rang the death knell for many animals, including the non-avian dinosaurs. But they never regained their prominence as a key member of the marine ecosystem, eventually dying out completely in the Eocene sometime around 40 million years ago (the Eocene lasted from 55 to 34 million years ago).

The fish reached sizes over 1.5 meters, which makes them on the large side, but not really big, considering there were mosasaurs in the same waters that surpassed 10 meters. Still, with fangs longer than 5 cm, they would not have been fun to tangle with. They were clearly effective predators on smaller fish and possibly soft animals like squid. At the same time, fossils have been found showing they were themselves prey for larger predators, such as sharks, the above-mentioned mosasaurs, plesiosaurs, and even flightless seabirds such as Baptornis. Baptornis was a toothed, predatory bird, but as it only reached 1 meter or so, it would have only been able to hunt young Enchodus. So like many of us today, Baptornis was always up for a good fish fry.

Hesperornis, a larger version of Baptornis, and a few Enchodus feeding on some herring-type fish. Picture by Craig Dylke.

Enchodus is often called the “saber-fanged herring,” although it is unrelated to herrings. So what then was it? Herrings are what is known as forage fish, meaning they are mostly prey items of larger fish and other animals. Most of the fish called herrings are in the family Clupeidae in the groups Clupeiformes, which includes such well-known fish as sardines and anchovies. Enchodus, on the other hand, has been placed into the group Salmoniformes, which includes trout, char, and of course, salmon. When one typically thinks of trout and salmon, one doesn’t think of bait fish, they think of the fish that eat the bait fish. Thus, Enchodus would better better described as a fanged salmon (they were a bit large to call them fanged trout).