Home » Paleontology » Fossils of Arkansas (Page 9)

Category Archives: Fossils of Arkansas

Mystery Monday!

It’s time for Mystery Monday! Here is a fossil that can be found in Arkansas, but is completely different from anything I’ve put up here before. Let’s see if you have the paleontological fiber needed to solve this puzzle, or do you lack the stomach for it? 🙂

Fossil Friday, to bear or not to bear, that is the question

It’s Friday again. Were you able to get the answer to Monday’s fossil?

The skull shown in the picture belonged to Arctodus simus, the giant, short-faced bear (the not-so-giant short-faced bear, A. pristinus, was smaller and lived in more southerly areas than A. simus). Arctodus lived in Arkansas and much of North America during the late Pleistocene, from less than 1 million years ago up to about 12,000 years ago, when most of the large North American Ice Age fauna went extinct. Arctodus was the North American version of the European cave bear, Ursus speleaous. While the European cave bear was a close relative of most modern bears, Arctodus was more distantly related, its only living relative being the spectacled bear, Tremarctos ornatus. It is sometimes considered possibly the largest terrestrial, mammalian carnivore that ever lived, standing over 3.5 m ( 11.5 ft) tall. Even on all fours, it was almost 2 m (6.5 f) at the shoulder. You would have to get at least 4.5 m (almost 15 ft) up a tree to avoid its reach, assuming it didn’t just tear the tree down or shake you out of the tree. It weighed in at a full ton and could run 40 mph (over 60kph). However, that is also the top range of modern Kodiak brown bears, otherwise known as Alaskan grizzly bears. In the wild, the bears don’t usually get over 1500 pounds (although they can), but the largest ever known was a bear in the Bismarck, ND zoo that weighed 2130 lbs at his death and previously weighed possibly close to 2400 lbs, although he was a very fat bear. There is another bear pelt on display at Space Farms Zoo and Museum in New Jersey that is claimed to be from a bear over 12 ft. tall and over 2,000 lbs, but those claims remain unverified are considered by most to be exaggerated. There is another bear that may have been even bigger. Arctotherium angustidens lived in South America about three million years ago and stood almost 3.5 m tall, so similar to Arctodus and the largest of extant bears, but was much more robust, weighing in the neighborhood of 3,500 lbs.

The skull shown in the picture belonged to Arctodus simus, the giant, short-faced bear (the not-so-giant short-faced bear, A. pristinus, was smaller and lived in more southerly areas than A. simus). Arctodus lived in Arkansas and much of North America during the late Pleistocene, from less than 1 million years ago up to about 12,000 years ago, when most of the large North American Ice Age fauna went extinct. Arctodus was the North American version of the European cave bear, Ursus speleaous. While the European cave bear was a close relative of most modern bears, Arctodus was more distantly related, its only living relative being the spectacled bear, Tremarctos ornatus. It is sometimes considered possibly the largest terrestrial, mammalian carnivore that ever lived, standing over 3.5 m ( 11.5 ft) tall. Even on all fours, it was almost 2 m (6.5 f) at the shoulder. You would have to get at least 4.5 m (almost 15 ft) up a tree to avoid its reach, assuming it didn’t just tear the tree down or shake you out of the tree. It weighed in at a full ton and could run 40 mph (over 60kph). However, that is also the top range of modern Kodiak brown bears, otherwise known as Alaskan grizzly bears. In the wild, the bears don’t usually get over 1500 pounds (although they can), but the largest ever known was a bear in the Bismarck, ND zoo that weighed 2130 lbs at his death and previously weighed possibly close to 2400 lbs, although he was a very fat bear. There is another bear pelt on display at Space Farms Zoo and Museum in New Jersey that is claimed to be from a bear over 12 ft. tall and over 2,000 lbs, but those claims remain unverified are considered by most to be exaggerated. There is another bear that may have been even bigger. Arctotherium angustidens lived in South America about three million years ago and stood almost 3.5 m tall, so similar to Arctodus and the largest of extant bears, but was much more robust, weighing in the neighborhood of 3,500 lbs.

Arctodus is generally known for its long legs and short face. However, research in the past decade has indicated that its legs were neither longer than expected, nor was its face all that short. It was simply big. Like other bears, it is thought to be fairly solitary most of the time. Contrary to many depictions, it was not particularly adapted to running quickly, considering that modern grizzlies can run 30 mph. What may have made people think they were unusually fast is a combination of their size giving them long legs and tracks that have indicated they used a pacing gait, with the legs on the same side of the body moving in unison, rather than in opposition like most other animals. This sort of gait is typically used in animals with longer legs or at faster trots. Camels use it and dogs and cats, among others, do it when maintaining a trot before they break into more of a gallop. However, the pacing gait is not indicative of a fast-running animal, but of an animal that maintains a quick pace for long distances, it bespeaks of endurance, not speed.

Like most bears, Arctodus is thought to have been omnivorous, eating both plants and animals. There have been several hypotheses concerning its diet, from mostly scavenging to hypercarnivorism. It was certainly capable of bringing down large prey, although its limbs were not as flexible as most high level predators, nor were they particularly robust for their size, leading some to think they scavenged, although they would be hard-pressed to compete with giant vultures in scavenging and recent work indicates the tooth structure was not sufficient for chomping through bone. They may have been better suited for foraging plant material with their unusually flexible wrist giving them an almost semi-opposable thumb, much like pandas. This suggests possible tree-climbing to some workers, although Arctodus was a very large animal to be climbing trees. Besides, it typically lived in more open, grassland environments the majority of the time, so it is unlikely to have been adapted for tree-climbing.

They went extinct roughly 11,000 years ago, along with a large number of other large species. A reduction in rich food supplies is thought to have caused the extinction of the large herbivores. This would have placed a great deal of stress on the carnivores, causing increased competition. The dire wolves lost out to the modern grey wolves during this time, chiefly thought to be a result of the gray wolves being able to hunt and subsist on smaller and fewer prey than the larger dire wolves. This same reasoning would apply to Arctodus as well, which had to compete against both wolves and other bears, for a greater percentage of the share to fuel its larger body. On the other hand, evidence for this hypothesis has been lacking in analyses of tooth wear.

If you want to see more of Arctodus, make your way to the La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles. many bones of this bear have turned up from the tar and are on display at the Page Museum.

Fossil Friday, a fossil of not quite mammoth proportions

It’s time to reveal the answer to Monday’s Mystery Fossil. We had three people who correctly identified this as the skull of Mammut americanum, the American Mastodon.

It’s time to reveal the answer to Monday’s Mystery Fossil. We had three people who correctly identified this as the skull of Mammut americanum, the American Mastodon.

Mastodon bones have been found throughout Arkansas, although almost all have been found either in northeast Arkansas between Crowley’s Ridge and the Mississippi River or along the Red River in Southwest Arkansas. According to the Arkansas State University Museum in Jonesboro, Arkansas has more mastodon finds than any other state in the mid-south region, with at least 20 different skeletons. Most of the work on them has been done by Dr. Frank Schambach and others of the Arkansas Archaeological Survey, headquartered at the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville, along with members of the Arkansas State University Museum. This particular mastodon was excavated by Dr. Schambach with the help of the Arkansas Archaeological Society along the Red River in Southwest Arkansas, I think in 1987, although I am not sure of the date yet.

Mastodons were related to elephants, although not as closely related to modern elephants as mammoths. Mammoths have also been found in Arkansas, most notably the Hazen mammoth, found in 1965. That specimen was a Columbian mammoth (Mammuthus columbi), a less hairy version of the wooly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius). They lived across much of North and Central America during the Miocene and Pliocene, although they are known mostly from the Pleistocene in Arkansas, the heyday of the Ice Age, which is when people traditionally think of them living. They were similar in size to modern elephants.

The teeth of mastodons, mammoths and modern elephants tell an interesting story. Modern elephants have a wide diet of vegetation from grass to fruit and tree limbs. The Asian elephant has teeth that are more plate-like in form, making a series of ridges that create an excellent grinding surface. African elephants spend more time in forests and bush lands, with a corresponding higher amount of bushy vegetation in their diet. Their teeth are large, multi-rooted teeth with a series of ridge-like cusps. Mammoths take the plate-like grinding surface to an extreme as an adaptation to the grasslands they frequented. Mastodons, on the other hand, specialized in the opposite direction, with large, prominent cusps suited to a more forested environment and diet. Thus, mastodons and mammoths formed a bracket surrounding elephant ecology.

Mastodon (left), Mammoth (right). http://www.igsb.uiowa.edu/

Work that has recently come out has shed new light on why they went extinct. People have long argued over whether climate change or humans wiped out the megaherbivores at the end of the last ice age. The Overkill hypothesis postulated that early humans hunted them to extinction. There is also the alternative that other actions by early humans contributed to their extinction. However, while there has been plenty of evidence indicating humans did hunt mammoths (e.g. the Clovis people at the Dent site in Colorado), the hypothesis has come under fire for the lack of widespread hunting evidence and timing issues, with research indicating the megaherbivores were already going extinct before humans appeared on the scene. The other hypothesis, climate change, has gotten more support from a study of plant fossils. According to the new data, the early tundra environments were dominated, not by grass, but by forbs, weedy herbaceous plants with more nutrients than grasses. An earlier glaciation 20-25,000 years ago dramatically reduced the abundance of these plants. When the weather warmed up, the forbs increased again, but never approached their previous levels. When the next glaciation hit, the forbs mostly died out, allowing the less nutritious grasses to take over, which greatly reduced the amount of herbivores the land could support. Of course, this does not mean that humans had nothing to do with the extinctions, but it does mean they were likely not the primary cause, more likely simply throwing the last spear into the coffin of the great herbivores.

That’s it for this week. Check back Monday for a new mystery fossil. Have a good weekend.

Mystery Monday Fossil of the Week

Our Mystery Monday fossil concerns a photo taken by the Arkansas Archaeological Society on one of their digs. I’m still trying to find when this was taken, but I know roughly where. Can you tell what it is they are uncovering?

Fossil, and Forum, Friday

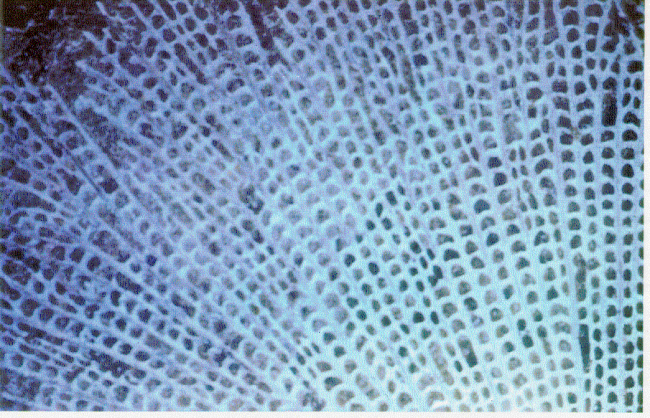

I’m sorry, but I forgot to post the Mystery Monday fossil on the blog. I posted the fossil on the Facebook page, but somehow failed to get it posted here, for which I apologize. Here is the fossil I posted, including the identifying portion cropped from the original picture. This image was taken from trilobites.info, a great website for all things trilobite.

It was correctly identified as a trilobite, although this one is the species Irvingella, not Bristolia as was guessed. Irvingella is very similar, but lacks the tail spine and the second set of spines is a little farther down the body. They are both listed as “fast-moving low-level epifaunal” feeders by the Paleobiology Database, which means they scurried quickly about over the ocean floor. But whereas Bristolia is thought to have been a deposit feeder, much like a crawfish, Irvingella was a carnivore, preying on worms, bugs, and such. They both lived in offshore marine environments, but whereas Bristolia has been found mostly in shallower waters, Irvingella has been found widespread from offshore throughout the continental shelf and even deeper water. This may have more to do with Bristolia having only been found in a few places in the southwestern United States while Irvingella has a much broader range throughout much of North America and Asia. They both lived in the Cambrian Period, although Bristolia seems to have lived a little earlier than Irvingella (there are some discrepancies in the published records making it difficult to compare exactly, this is partly due to revisions of the time scale and refinements in age estimates over the decades making detailed comparisons problematic).

Since our last Forum Friday recap, we have started a new year. We have reviewed the Walking with Dinosaurs movie. We identified an Exogyra ponderosa oyster, Archimedes bryozoan, Aetobatus eagle ray, and this Irvingella trilobite.

Over on the Facebook page so far this year, we have seen some amazing animals, including sharks that glow in the dark, a fish that walks on land, and a caterpillar who’s tobacco breath repulses spiders. We even learned why sharks don’t make bone, but polygamous mice have big penis bones and an organism that changes its genetic structure seasonally.

A green biofluorescent chain catshark (Scyliorhinus retifer). Livescience.com. Credit: ©J. Sparks, D. Gruber, and V. Pieribone

We saw two articles on fighting dinosaurs. We learned how they took over the planet and discussed scaly dinosaurs for a change. We found out some ancient marine reptiles were black and Tiktaalik had legs.

A lot of articles hit the press on human evolution in 2013. We also found out (some) humans developed the ability to tolerate lactose to not starve and how we smell sickness in others. We also found a great book on Evolution & Medicine. We also saw evidence of how our actions affect the evolution of other animals and someone who thinks they can understand dog language.

We read that plants may have caused the Devonian extinction event, a genetic study saying placental mammals originated before the end-Cretaceous extinction event despite no fossils ever having been found, and that small mammals with flexible schedules handle climate change better than big mammals that keep a stricter schedule.

We found a great , concise explanation of evolution and three different short videos on the history of life on earth, two of them animated and set to music. We also heard Neal DeGrasse Tyson urge more scientists to do more science outreach (and how to cook a pizza in 3 seconds). Unfortunately, we also heard about the deplorable conditions during filming on Animal Planet and creationism in Texas public schools, as well as how the failure to take evolution into account can screw up conservation efforts.

So what did you like? Did you guess the fossil? Is there anything you want to see? Let us know.

Fossil Friday

Another week has gone by and so little done here. I started my Vertebrate paleontology class this week and if you think it takes a lot of work to take one, just imagine the amount of time it takes to design one.

So today, we announce the mystery fossil from Monday. Did you have any idea what it was? It stumped everyone on the Facebook page, so if you couldn’t figure it out, don’t feel bad. It was a hard one. These are not terribly uncommon fossils, but most people are completely unfamiliar with them, despite the fact that anyone who visits a public aquarium has seen its living relatives.

This is part of a tooth plate from a ray, most likely Aetobatus, the eagle ray. They are filter feeders eating plankton and have been around since the Miocene 20 million years ago. While none have been found in Arkansas that I know of, they have been found in pretty much every state around us, so I expect so collector out there somewhere has probably found some here. Check us out Monday for a new fossil!

UPDATE: I need to correct a mistake I made in this post. Eagle rays, like Aetobatis here, were and are not filter feeders. The large rays, like the Manta ray in the same family, are indeed filter feeders, the smaller rays, like Aetobatus and its close relative Myliobatis, another ray that lived in the area at the same time (as well as earlier in the Eocene over 40 million years ago), were durophagous, meaning they used their teeth to crush shelled prey, such as clams, crabs, and shrimp. The main part of the tooth brought to bear on the prey item is the flat, plate-like part.

For this picture and much more information on the current species of eagle rays, go to the Florida Museum of Natural History.

For this picture and much more information on the current species of eagle rays, go to the Florida Museum of Natural History.

Fossil Friday

It has been a strange week, what with trying to catch up from the holidays and all. So this post will be brief. On Monday, I posted this picture of a commonly found fossil in Arkansas, provided you look in the right places. Here were the clues.

Clue 1: It’s from the Cretaceous.

Clue 2: It’s modern day relatives are widely considered a delicacy.

Clue 3: This is no wilting lily. This creature is big and bold. It shows how twisted it is on the outside for all the world to see. Dude, that’s heavy.

Were you able to figure it out?

So for the final reveal: Exogyra ponderosa. Allie Valtakis was able to figure out it was a mollusc, specifically a bivalve (clam), in the Order Ostreoida, Family Gryphaeidae. While mosasaurs swam the oceans and dinosaurs walked the shores, these Late Cretaceous oysters made huge oyster beds throughout the coastal waters. Like all oysters, they were filter-feeders, collecting microscopic particles of food from the water. You can find them in south-central Arkansas within several rock units, but most particularly in the Marlbrook Marl, a limy mudstone. They are known for their large, heavy, rough bottom shell with a curled, hornlike part near the hinge. The top shell is much smaller and flatter, but still a good size, something like a cap on a coffee cup, if your coffee cup was kind of bowl-shaped. They are sometimes called Devil’s toenails, but that name usually refers to a different clam called Gryphaea, an oyster that is also in the Family Gryphaeidae, but a different subfamily. If you look under a microscope at the shell, you may notice that it is very porous, giving the Family the nickname of foam or honeycomb oysters. Some are still alive today, such as Hyotissa hyotis, the giant honeycomb oyster

E. ponderosa was one of the earliest clams of this genus that was named, by Ferdinand Roemer in 1852, a German lawyer who gave up law to study geology in Texas, thus his title as the Father of the Geology of Texas. You can fossils of them from Texas to New Jersey and Delaware, south through Mexico and Peru.

Until next time, as Dr. Scott The Paleontologist would say, ‘Get out there, get into nature, and make your own discoveries.”

Mystery Monday and Walking With Dinosaurs Movie Review

Mystery Monday

Last Friday I posted clues to a mystery fossil. The clues were 1) I lived in AR during the Mississippian Period roughly 330 million years ago and am a very common fossil to find here. 2) Many people think I’m a coral, but I’m not. 3) I am named after a famous Greek mathematician and inventor. Who, or more precisely, what am I? Allie Valtakis got the right answer as the bryozoan, Archimedes. Here is what the Arkansas Geological Survey says about it.

The Bryozoa grow attached to the sea-floor as do corals, but they differ significantly from corals in terms of soft-part anatomy. The bryozoans are exclusively colonial and fall into two broad groups, the lacy colonies and the twig-shaped colonies. Individual “houses” (zooeciums) lack the radial partitions found in corals, but they are divided transversely by partitions called diaphragms (Fossils of Arkansas). Bryozoans can also grow as incrustations on the shells of other organisms and are commonly associated with reef structures.

“Bryozoans are tiny colonial marine animals that are present in marine and fresh water today. They are sessile benthonic animals (fixed to seabed) that are filter feeders and prefer shallow seas, living fairly close to shore (neritic). One bryozoan called Archimedes (see picture below) is abundant in Mississippian age rocks in Arkansas and is so plentiful that one of the rock formations called the Pitkin Limestone was once referred to as the “Archimedes Limestone”. Generally, only small pieces of bryozoans that resemble “fronds” are preserved in Mississippian and Pennsylvanian age rocks in the Ozark Plateaus Region.

References:

Freeman, Tom, 1966, Fossils of Arkansas: Arkansas Geological Commission

Bulletin 22, 53 p., 12 pls., 15 figs., 1 map.

Way to go, Allie!

Can you guess this week’s fossil? I will do things a bit differently this time. Unlike previous fossils, in which I told people on the Facebook page as soon as someone provided the correct answer, I will not reveal the answer until Friday, so you have plenty of time to give it a try. In addition to the picture (note the scale) below, I will provide one clue every day until Friday. Good luck!

Clue 1: It’s from the Cretaceous.

Clue 2: It’s modern day relatives are widely considered a delicacy.

Clue 3: This is no wilting lily. This creature is big and bold. It shows how twisted it is on the outside for all the world to see. Dude, that’s heavy.

Come back tomorrow for the answer! You can also find it on the Facebook page.

Walking with Dinosaurs 3D movie review

I went to see Walking With Dinosaurs 3D this weekend. My kids were interested in seeing the movie and I liked the BBC “Walking with Dinosaurs” TV mini-series, so we were all eagerly anticipating the movie. I had read a few reviews of the movie, some by paleo people, who said the dinosaurs were great, but the voices were terrible, which gave me pause, but it’s a BBC movie on dinosaurs, how bad could it be, right?

Sad to say, I have to agree with most of the reviewers. This movie may be much more enjoyable if you can’t hear it. To begin with, whatever expectations you may have, forget them. If you are going in expecting to see a big screen version of the BBC “Walking with Dinosaurs,” you will be disappointed by the cartoon voices and plot. If you are looking for light entertainment for little kids, you might be a bit surprised by the rather jarring breaks providing a subpar, documentary-style educational interlude which will kick everyone out of the story.

The film reminded me nothing so much as a cross between the BBC documentary-style series and The Land Before Time movie series, failing at both. I think the reason for this is because it seemed to clearly start off with the idea of it being a kid-friendly movie along the lines of the TV series, but some executive decided after it was made that it was not going to draw enough kids. So the movie was recut and really bad dialogue added to it instead of the normal narration one would expect in a nature documentary, along with completely superfluous modern scenes bookending the film, wasting the talents of otherwise fine actors. The voices were obviously added as an afterthought because the dinosaurs do not act like they are speaking. I could even occasionally hear the original dinosaurian bleating and honking in the background even as they are supposedly talking. The dialogue, as Brian Switek noted in his review, destroyed any emotion that may have been evoked by the scenes that were supposed to be emotionally powerful. What should have been poignant, heart-tugging scenes were drained of any impact by juvenile pratterings that never ceased. I found myself wishing for the dinosaurs to just shut up once in a while. As a result, it is a movie that may be enjoyable for a little kid, but eminently forgettable. Bambi was a much more riveting emotional experience, not to mention more educational about the lives of deer.

The story line was inconsistent with the idea of a nature documentary and a poor choice for a dinosaur movie. Whether or not the worst aspects of it were in the original script, I don’t know, but the final plot, while suitable for a cartoon Land Before Time, was wholly inappropriate for a nature “fauxmentary.” For a film that was supposedly educational, it pushed moral viewpoints which are only valid in human cultural environments and completely invalid in the natural world. The idea that intelligence and courage will overcome the thoughtless, testosterone-fueled belligerence of the larger alpha males is a noble sentiment and may work in a human context, but not in the depicted dinosaur society. Control of a herd of large herbivores that have evolved extravagant displays will never pass to the runt of a litter because he saves the herd in a time crisis due to his quick thinking. The plot line for the movie is far more appropriate to an after-school special involving actual, human children, not dinosaurs. As such, it completely destroys any educational effectiveness of the movie. The only education that remains is that dinosaurs lived in a snowy Alaska and that some dinosaurs had feathers, particularly the smaller theropod carnivores. I really like this aspect of the movie, but its authenticity in these aspects was completely undermined by the silliness of the rest of the movie.

To make it even more confusing in terms of genre plotting, the movie shows that females in the herd are dominated by the alpha male, but glosses over what that means in terms of sexual dominance. In a kid-based movie, this understandably only goes as far as hanging out with each other. In the natural world (and post-adolescent human worlds), as every adult in the audience will understand, it means the female submits to the alpha male’s sexual advances. In terms of a human kid’s movie, it sends very poor messages about the role of females in society. In terms of an educational nature show, it is intentionally misleading to spare the typical parental sensibilities of what is appropriate for kids to see.

In short, if you go to see this movie (which I would really recommend waiting until a rental, as it is not worth spending the price for a 3D movie), go expecting to see a mindless 80 minutes of passable, but forgettable, entertainment for children with no real educational value other than to say look, aren’t dinosaurs neat? Enjoy the graphics, ignore the rest.

“Arkansaurus,” the only Arkansas Dinosaur

Welcome to the first of a series on Arkansas fossils. Arkansas is not generally known as a mecca for dinosaur lovers. Most of the dinosaurs in Arkansas are statues created by a man named Leo Cate, which have all the accuracy of the old plastic toys on which he based the statues, which is to say, not much (of course, he made them for enjoyment, not as anatomical models, so they serve their purpose). Nevertheless, dinosaurs are the first thing I get asked about when I give talks in schools, so I decided to start off with a discussion of our one and only dinosaur, called “Arkansaurus fridayi.”

Ordinarily, I would not delve into how a fossil was found here, but because Arkansaurus is unique and illustrative of how many fossils are brought to the attention of science, a brief synopsis of the story of how it was brought to the attention of science may be of interest. In August, 1972, Joe Friday was searching for a lost cow on his property near Lockesburg in Sevier County, when he found some bones eroding out of a shallow gravel pit. He showed them to a Mr. Zachry, whose son, Doy, happened to be a student at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville. Doy showed the bones to Dr. James H. Quinn, a professor at UA, who identified them as part of the foot of a theropod dinosaur. He contacted the Arkansas Geological Survey and Dr. Quinn, Ben Clardy of the AGS, and Mr. Zachry went back to the site where they found the rest of the bones. Dr. Quinn presented the bones at a meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology where he discussed the bones with Dr. Edwin Colbert, a noted paleontologist who was an expert in dinosaurs and vertebrate evolution. They came to the conclusion that the bones probably came from some type of ornithomimid, a group of ostrich-like dinosaurs (the name literally means bird-mimic), one of which, named Gallimimus, was made famous in Jurassic Park. Despite further excavations, no additional bones have been found. Dr. Quinn never officially described the bones, publishing only an abstract for a regional meeting of the Geological Society of America in 1973. It remained for Rebecca Hunt-Foster, now a paleontologist for the Bureau of Land Management, to publish the official description 30 years later in the Proceedings Journal of the 2003 Arkansas Undergraduate Research Conference.

Ordinarily, I would not delve into how a fossil was found here, but because Arkansaurus is unique and illustrative of how many fossils are brought to the attention of science, a brief synopsis of the story of how it was brought to the attention of science may be of interest. In August, 1972, Joe Friday was searching for a lost cow on his property near Lockesburg in Sevier County, when he found some bones eroding out of a shallow gravel pit. He showed them to a Mr. Zachry, whose son, Doy, happened to be a student at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville. Doy showed the bones to Dr. James H. Quinn, a professor at UA, who identified them as part of the foot of a theropod dinosaur. He contacted the Arkansas Geological Survey and Dr. Quinn, Ben Clardy of the AGS, and Mr. Zachry went back to the site where they found the rest of the bones. Dr. Quinn presented the bones at a meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology where he discussed the bones with Dr. Edwin Colbert, a noted paleontologist who was an expert in dinosaurs and vertebrate evolution. They came to the conclusion that the bones probably came from some type of ornithomimid, a group of ostrich-like dinosaurs (the name literally means bird-mimic), one of which, named Gallimimus, was made famous in Jurassic Park. Despite further excavations, no additional bones have been found. Dr. Quinn never officially described the bones, publishing only an abstract for a regional meeting of the Geological Society of America in 1973. It remained for Rebecca Hunt-Foster, now a paleontologist for the Bureau of Land Management, to publish the official description 30 years later in the Proceedings Journal of the 2003 Arkansas Undergraduate Research Conference.

The first thing to know about this particular dinosaur is that “Arkansaurus fridayi” is not its real name. In fact, it doesn’t even have an official name. The reason for this is because all we have of it is part of one foot. Specifically, we have the metatarsals, a few phalangeal bones, and the unguals. In non-science speak, on humans, they would refer to the bones making up the front half of your foot. The metatarsals are the long bones the toes are attached to forming the front part of the arch, the phalanges are the toes, and the unguals are the bony cores of the claws. The pictures show the actual bones and a cast, in which the missing phalangeal bones have been restored. The real fossil has all the phalangeal bones connecting to the metatarsals and all the unguals, but a couple of the middle phalanges are missing. We have no ankle bones and nothing at all of the rest of the animal. With such little to go on, it has been difficult to determine exactly what kind of dinosaur it is, so no scientist has been comfortable giving it an official name yet. To add to the complications, not a whole lot of feet from theropod dinosaurs are known, so good comparison material is limited, and little is known about theropods in the southern United States to begin with. (Aside: dinosaurs are separated into two groups. The Ornithischia, which are comprised of the herbivorous, mostly four-footed dinosaurs; and the Saurischia, which include the giant, long-necked sauropods and the bipedal, mostly carnivorous theropods.)

So why only one foot? What happened to the rest of it? I’ll let Rebecca Hunt-Foster explain it, as she did an excellent job: “There are several possibilities that would explain the occurrence of a single foot at the Friday site. It is a possibility that the rest of the Friday specimen could be gravel on highway 24. Road crews could have cut into the Trinity Group (Ed. Note. The rock formation in which the bones were found) when excavating the Quaternary gravel that lies directly above it, when building the road in 1954. As another theory, the animal may have begun to decompose before its body was carried by water to the site of deposition. Consequentlly, bits and pieces could have been scavenged by predators in the Lower Cretaceous, resulting in only a single foot remaining for preservation. Finally, it is possible that the entire specimen was preserved but that most of the skeleton was lost to Pleistocene erosion.” So just think about that the next time you go driving down the road. What fossils might you be driving upon?

Even if we don’t know for sure what it is, we do have some clues and can narrow down, at least a little, what it might be. What we know for sure is that it is some kind of coelurosaur. That, unfortunately, doesn’t help us a lot because coelurosaurs cover everything from little compsognathids to giant tyrannosaurs to modern birds, known principally for having bigger brains than earlier theropods, slender feet with three toes, and many of them had feathers. It does tell us it is not closely related to dinosaurs like allosaurs and spinosaurs, nor to early theropods like ceratosaurs and Coelophysis. Dr. James Kirkland opined that it was similar to Nedcolbertia, a small coelurosaur found in Utah. The problem here is that no one knows much more about Nedcolbertia either and its relationships to other dinosaurs are unclear. Quinn and Colbert thought it may have been an ornithomimid, but closer inspection by Rebecca Hunt-Foster and comparison with known ornithomimids indicates this is unlikely. Right now, all that can really be said is that it is likely a small coelurosaur, but not a tyrannosaurid, ornithomimid, or advanced form more closely related to birds, which leaves a small group of poorly known coelurosaurs no one really knows what to do with.

Even if we don’t know for sure what it is, we do have some clues and can narrow down, at least a little, what it might be. What we know for sure is that it is some kind of coelurosaur. That, unfortunately, doesn’t help us a lot because coelurosaurs cover everything from little compsognathids to giant tyrannosaurs to modern birds, known principally for having bigger brains than earlier theropods, slender feet with three toes, and many of them had feathers. It does tell us it is not closely related to dinosaurs like allosaurs and spinosaurs, nor to early theropods like ceratosaurs and Coelophysis. Dr. James Kirkland opined that it was similar to Nedcolbertia, a small coelurosaur found in Utah. The problem here is that no one knows much more about Nedcolbertia either and its relationships to other dinosaurs are unclear. Quinn and Colbert thought it may have been an ornithomimid, but closer inspection by Rebecca Hunt-Foster and comparison with known ornithomimids indicates this is unlikely. Right now, all that can really be said is that it is likely a small coelurosaur, but not a tyrannosaurid, ornithomimid, or advanced form more closely related to birds, which leaves a small group of poorly known coelurosaurs no one really knows what to do with.

Using these animals as a comparison, what can we say about what kind of animal “Arkansaurus” was? It was likely a fast runner with probably an omnivorous diet, eating smaller animals and supplementing its diet with plants. It would likely have stood somewhere between 2-4 meters (6.5-13 feet) tall. It would have looked something like an ostrich with long arms ending in hands with three functional fingers, with one of them being at least semi-opposable, and a jaw filled with small teeth. If it had feathers (which seems increasingly likely), the feathers would have looked more like fur than the large feathery plumage seen on ostriches today. It would also have had large eyes like ostriches, with excellent color vision, based on the fact that its nearest living relatives, crocodilians and birds, all see a broad spectrum of colors (even better than humans).

The rocks the bones were found in were part of what is called the Trinity Group. These rock layers (or strata) consist of layers of sand, clay, gravel, limestone, and gypsum laid down in the Early Cretaceous Period, roughly around 100-120 million years ago (what is known as the Albian and Aptian Ages). The rocks indicate that during the time the rocks were formed, the environment was a shallow marine coastal area not unlike south Texas near the Rio Grande or in the Persian Gulf. Our dinosaur would certainly not have been alone. There were other dinosaurs in the vicinity, we just know very little about them. Sauropods left thousands of tracks in the coastal sediment forming a massive trackway found in a Howard Country gypsum mine in 1983. Another trackway found in 2011 has tracks from sauropods such as Pleurocoelus and Paluxysaurus (which may or may not refer to the same species and may or may not also be called Sauroposeidon) as well as tracks from what was probably the giant theropod Acrocanthosaurus.

The rocks the bones were found in were part of what is called the Trinity Group. These rock layers (or strata) consist of layers of sand, clay, gravel, limestone, and gypsum laid down in the Early Cretaceous Period, roughly around 100-120 million years ago (what is known as the Albian and Aptian Ages). The rocks indicate that during the time the rocks were formed, the environment was a shallow marine coastal area not unlike south Texas near the Rio Grande or in the Persian Gulf. Our dinosaur would certainly not have been alone. There were other dinosaurs in the vicinity, we just know very little about them. Sauropods left thousands of tracks in the coastal sediment forming a massive trackway found in a Howard Country gypsum mine in 1983. Another trackway found in 2011 has tracks from sauropods such as Pleurocoelus and Paluxysaurus (which may or may not refer to the same species and may or may not also be called Sauroposeidon) as well as tracks from what was probably the giant theropod Acrocanthosaurus.

Most of the information and images in this post not directly linked to came from the following sources. Many thanks to Rebecca Hunt-Foster for clean pictures from her paper, which she also graciously supplied.

Hunt, ReBecca K., Daniel Chure, and Leo Carson Davis. “An Early Cretaceous Theropod Foot from Southwestern Arkansas.”Proceedings Journal of the Arkansas Undergraduate Research Conference 10 (2003): 87–103.

Braden, Angela K. The Arkansas Dinosaur “Arkansaurus fridayi”. Little Rock: Arkansas Geological Commission, 1998.

The top image is a Leo Cate T. rex. Photo by Debra Jane Seltzer, RoadsideArchitecture.com.

UPDATE: Arkansaurus has recently been named the Arkansas official state dinosaur, reviving interest in the fossil. It is currently being re-examined by Dr. Rebecca Hunt-Foster, with the hopes that new fossils and information that has come to light since her last publication will provide a more refined determination of its relationships.