Home » Paleontology (Page 4)

Category Archives: Paleontology

National Fossil Day Post #2: The Most Common Fossils of Arkansas

National Fossil Day is today. The Museum of Discovery is having their second annual National Fossil Day event this Saturday. In celebration of these events, I am reviewing important fossils of Arkansas. Last post I stated my picks for the most famous fossils of Arkansas. This time I will discuss what I think are the most common fossils in particular regions of the state.

In the Ozarks, you can find an abundance of marine fossils. There are ammonoids, bryozoans, brachiopods, clams, corals, echinoids, and many others. The Pitkin limestone is so chocked full of Archimedes bryozoans that it is sometimes referred to as the Archimedes limestone. But overall, I have to go with crinoids as the most commonly found fossil in the Ozarks. Crinoids lived throughout the Paleozoic Era, making them potential finds throughout the region. They survived even up to the present day in deep marine settings, but in the Paleozoic, they lived throughout the shallow marine realm, which is where fossils are most common.

In the Ozarks, you can find an abundance of marine fossils. There are ammonoids, bryozoans, brachiopods, clams, corals, echinoids, and many others. The Pitkin limestone is so chocked full of Archimedes bryozoans that it is sometimes referred to as the Archimedes limestone. But overall, I have to go with crinoids as the most commonly found fossil in the Ozarks. Crinoids lived throughout the Paleozoic Era, making them potential finds throughout the region. They survived even up to the present day in deep marine settings, but in the Paleozoic, they lived throughout the shallow marine realm, which is where fossils are most common.

Stellar examples of crinoids in all their fossilized glory. This image and more information can be found at http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/echinodermata/crinoidea.html

Known as sea lilies today due to their plant-like appearance, they are actually echinoderms, making them relatives of sea urchins and sea stars. While not common today, they were quite abundant during the Paleozoic. Most of the fossils of crinoids are of their stems, which look like stacks of circles with the centers punched out, sort of like flattened rings. But occasionally, you can find the tops of the crinoids with the body (called a calyx) and the arms still intact. These are rare because, like all echinoderms, the body is made of plates that fall apart into indistinguishable fragments shortly after death.

Graptolites from the Womble shale. http://www.geology.ar.gov

You will not find many fossils in the Ouachitas, but two types of fossils are commonly found there, conodonts and graptolites. Conodonts are the toothy remains of the earliest vertebrates. Unfortunately, you can place several of them on the head of a pin, so unless you are looking at rocks under a microscope, you probably won’t see them. That leaves graptolites, which can be found in several places fairly easily. Unless you know what you are looking at, they can be easy to miss. On black shale, they often appear as pencil scratches that are easy to overlook. But look closely and you will see that many of them look like tiny saw blades. These are what remains of animals we call today pterobranchs. These animals are the closest an animal can get to being a chordate, the group that includes vertebrates, without actually being one. So the Ouachita mountains have fossils that bracket that hugely important transition from spineless to having a backbone.

You will not find many fossils in the Ouachitas, but two types of fossils are commonly found there, conodonts and graptolites. Conodonts are the toothy remains of the earliest vertebrates. Unfortunately, you can place several of them on the head of a pin, so unless you are looking at rocks under a microscope, you probably won’t see them. That leaves graptolites, which can be found in several places fairly easily. Unless you know what you are looking at, they can be easy to miss. On black shale, they often appear as pencil scratches that are easy to overlook. But look closely and you will see that many of them look like tiny saw blades. These are what remains of animals we call today pterobranchs. These animals are the closest an animal can get to being a chordate, the group that includes vertebrates, without actually being one. So the Ouachita mountains have fossils that bracket that hugely important transition from spineless to having a backbone.

For the third choice, one could always argue for shark teeth, which are commonly found in southwest Arkansas, but can be found most anywhere in the state. But if we limit our discussion to the southwest part of the state, the easiest to find on the basis of quantity and size I think has to go to Exogyra ponderosa. These are Cretaceous aged oysters known for their thick shells adorned with a curled hornlike shape. They are big, sturdy, and can be found by the thousands. One can only imagine that the Cretaceous was a great time to be an oyster. At that time, southwest Arkansas was beachfront property. with lots of shoreline and shallow marine deposits of sand, shale, limestone, and the famous Cretaceous chalk deposits. Dinosaurs walked along the beach, marine reptiles like mosasaurs and elasmosaurs plied the waters, along with sharks and fish of all kinds. And between them lay mountains of oysters.

For the third choice, one could always argue for shark teeth, which are commonly found in southwest Arkansas, but can be found most anywhere in the state. But if we limit our discussion to the southwest part of the state, the easiest to find on the basis of quantity and size I think has to go to Exogyra ponderosa. These are Cretaceous aged oysters known for their thick shells adorned with a curled hornlike shape. They are big, sturdy, and can be found by the thousands. One can only imagine that the Cretaceous was a great time to be an oyster. At that time, southwest Arkansas was beachfront property. with lots of shoreline and shallow marine deposits of sand, shale, limestone, and the famous Cretaceous chalk deposits. Dinosaurs walked along the beach, marine reptiles like mosasaurs and elasmosaurs plied the waters, along with sharks and fish of all kinds. And between them lay mountains of oysters.

You may notice that I left out pretty much all of eastern Arkansas. That is because that region of the state is covered in fairly recent Mississippi river sediment, so you don’t find that many fossils in that part of the state. Some have been found, such as the Hazen mammoth, mastodons, sea snakes, and the occasional giant ground sloth or whale, but the fossils are few and far between. So while they have several fascinating fossils, they aren’t going to show up on anyone’s list of commonly found fossils.

So those are my choices. Do you have other suggestions?

National Fossil Day Post #1: The Most Famous Fossils of Arkansas

This week is Earth Science Week, with National Fossil Day on Wednesday. The Museum of Discovery is holding its second annual National Fossil Day event on Saturday, the 17th, between 10 am and 3 pm. So in honor of the week and in preparation for the museum event on Saturday, I thought I would briefly talk about what I consider the three most famous fossils found in Arkansas. You may notice this list is exclusively vertebrates. That is because of the rather large bias in popularity vertebrates have over invertebrates. Vertebrates are much less common in Arkansas than invertebrates, but they get almost all the press. Let me know in the comments section if you have any other contenders.

The first contender for Arkansas’s most famous fossil is Arkansaurus, the only dinosaur to have been found in the state. Found in 1972 in Sevier County, the only bones found comprised the front half of one foot. Despite considerable searching, nothing else has ever been found. The lack of diagnostic bones has made it impossible to determine exactly what kind of dinosaur it was. All that can really be said is that it is some kind of coelurosaur, a type of theropod, but not a tyrannosaurid, ornithomimid, or any other more derived form related to birds. We can also say it was a medium-sized dinosaur, meaning it wasn’t terribly small, as the front half of the foot measures just over two feet long. A statue was made by Vance Pleasant, which was recently seen at the Museum of Discovery as part of a dinosaur exhibit. How accurate is it? It’s a reasonable estimate based on what we know right now, which is not much, except that the real animal probably had some form of feathers not seen on the statue. The fossils are currently housed at the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville.

The first contender for Arkansas’s most famous fossil is Arkansaurus, the only dinosaur to have been found in the state. Found in 1972 in Sevier County, the only bones found comprised the front half of one foot. Despite considerable searching, nothing else has ever been found. The lack of diagnostic bones has made it impossible to determine exactly what kind of dinosaur it was. All that can really be said is that it is some kind of coelurosaur, a type of theropod, but not a tyrannosaurid, ornithomimid, or any other more derived form related to birds. We can also say it was a medium-sized dinosaur, meaning it wasn’t terribly small, as the front half of the foot measures just over two feet long. A statue was made by Vance Pleasant, which was recently seen at the Museum of Discovery as part of a dinosaur exhibit. How accurate is it? It’s a reasonable estimate based on what we know right now, which is not much, except that the real animal probably had some form of feathers not seen on the statue. The fossils are currently housed at the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville.

My vote for the Arkansas fossil that is more widely known outside the state better than inside it is Ozarcus, a primitive shark found by the paleontologists Royal and Gene Mapes in the Ozark Mountains near Leslie. The reason for the fame of this fossil is that it is the oldest known shark fossil that preserves the gill supports, known as the branchial basket. These normally do not preserve because they are made of cartilage, much like most of the rest of the shark skeleton. The gill supports here indicated that both sharks and osteichthyans, or bony fish, evolved from an ancestor that looked more like bony fish than it did the cartilaginous sharks, meaning that the original sharks were not primitive to bony fish, but possibly evolved after the appearance of bony fish. Due to this, Ozarcus got international coverage and became well known to paleontologists. The fossil currently resides at the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

My vote for the Arkansas fossil that is more widely known outside the state better than inside it is Ozarcus, a primitive shark found by the paleontologists Royal and Gene Mapes in the Ozark Mountains near Leslie. The reason for the fame of this fossil is that it is the oldest known shark fossil that preserves the gill supports, known as the branchial basket. These normally do not preserve because they are made of cartilage, much like most of the rest of the shark skeleton. The gill supports here indicated that both sharks and osteichthyans, or bony fish, evolved from an ancestor that looked more like bony fish than it did the cartilaginous sharks, meaning that the original sharks were not primitive to bony fish, but possibly evolved after the appearance of bony fish. Due to this, Ozarcus got international coverage and became well known to paleontologists. The fossil currently resides at the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

blog.arkansas.com/post/a-pre-historic-visitor-comes-to-the-lower-white-river-museum-state-park-in-des-arc/

The last contender for Arkansas’s most famous fossil is the Hazen Mammoth, the only mammoth known from the state. Found in 1965, it consisted of the skull, tusks, and some vertebra. There was a lot more of the skeleton found, but unfortunately, the bones were very soft and were severely damaged or destroyed before they could be collected. The bones were identified as Mammuthus columbi, or the Columbian Mammoth, a less hairy version of the more commonly known woolly mammoth, indicating warmer temperatures than found in areas in which the woolly mammoth is known. Even though only one mammoth has been found in Arkansas, upwards of two dozen mastodons have been found. Mastodons were smaller cousins of the mammoths and preferred forest habitats over the grassy plains in which the mammoths lived. This provides evidence that much like today, the state was mostly forested during the Pleistocene Period in which they lived. Today, the mammoth is a resident of the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville.

So what would you call the most famous fossil of Arkansas?

Getting Antsy for the Answer to last Week’s Mystery Monday?

Last week we posted a new fossil. Were you able to figure it out?

This particular picture is of the ant, Nylanderia vetula, caught in Dominican amber. Dominican amber is from the Miocene, currently thought to be about 25 million years old. The fossil ants from Arkansas are a bit different.

In 1974, ants were found in amber collected near Malvern, Arkansas, from the Claiborne formation, which is listed as being from the Eocene, roughly 45 million years ago (give or take 3 million years). According to the Arkansas Geological Survey, the Claiborne is a series of fine sand to silty clay layers, with interspersed layers of lignite. The lignite and amber are clearly indicative of terrestrial environments, although there are some marine sediments within the formation. A number of fossils have been found in the formation, including fish and reptile bones and teeth, leaf impressions, trace fossils, and of course, wood and amber.

The specific ants that have been found were identified as Protrechina carpenteri. These ants are in the group Formicinae, one of the more common ant groups. Interestingly, the Eocene ants were anything but common. Ants during this time shifted from the earlier ants to a more modern collection of species. They were quite diverse, with Phillip Ward reporting that David Archibald claimed some of them were the “size of small hummingbirds”.

Titanomyrma lubei (not from Arkansas).

Images of our Arkansas fossil ant are hard to find, as in, I couldn’t find a single image. However, if you want to see the real thing, go to the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology, where Antweb.org reports it is being held. Yet another Arkansas fossil in the hands of another state.

Fossils of Arkansas

For those of you who are new to the website, under the Arkansas Fossils tab is a list of fossils that have been reported in Arkansas. For those of you returning to the site, you will find a new addition to the page. Using the Arkansas Geological Survey regions map, I have marked where in the state fossils have been found. Want to know where to find conodonts? Looking for dinosaurs? Check the map to get a general location.

At some point, I would like to make the map interactive, so that visitors can click on the map and be taken to information about that fossil. Unfortunately, I do not yet have the technical ability to do that for this WordPress template. Should someone find such task within their abilities and has an interest in contributing to the site, please contact me.

Here is the map you can find on the fossils page.

Mystery Monday

Time for a new Mystery Monday fossil. The fossil on display here was found in Dominican amber, as well as Russia. But it has also been found in Arkansas and played a role in our understanding of the evolution of this group of animals. Leave your identifications in the comments section and come back Friday for the answer.

Basilosaurus, the Bone Crushing Whale That Was Mistaken For a Lizard

Last week we saw this vertebra and lower jaws of Basilosaurus.

The history of Basilosaurus is intimately tied to Arkansas. Alabama and Mississippi may have claimed Basilosaurus as their state fossil (and indeed the fossils are much more common in those states), but it was an Arkansan that found them. Judge Bry found some bones in the Louisiana portion of the Ouachita River in 1832 and sent them to Dr. Richard Harlan at the Philadelphia Museum. After examination of these bones, along with more bones sent by Judge Creagh from Alabama, Dr. Harlan noted similarities with plesiosaur vertebrae, only twice the size, so in 1834 he named the animal Basilosaurus, king of the reptiles.

In 1838, more bones were discovered in Arkansas, near Crowley’s Ridge. E. L. Palmer published a brief note on them in 1839. Meanwhile, Dr. Harlan had taken his bones to the United Kingdom to see the esteemed Sir Richard Owen, the most prominent paleontologist of his day (even today, he is considered one of the most important researchers in the field). Sir Owen found that the bones were not from a reptile at all, but from a whale. Therefore, he proposed changing the name to Zeuglodon. However, the rule of precedence requires the first name to take priority, so Basilosaurus it is.

Basilosaurus has an important place in the study of whale evolution. In addition to being the first primitive whale identified, Basilosaurus was the first true whale that was an obligate aquatic animal. Since its discovery, several other species have been found, but they all still retain enough limb function to move, however awkwardly, on land. Basilosaurus, due to its size and having no functional limbs other than some small flippers, would have been unable to move on land. As can be seen in the chart above, Basilosaurus was not the ancestor of modern whales, though. It appears that Dorudon, a close relative, had that honor.

Basilosaurus was a huge animal, reaching more than 15 m (50 feet). Neither it nor Dorudon had the forehead melon characteristic of modern cetaceans, which indicates it likely did not have echolocation, but did have very powerful jaws, clearly indicative of its carnivorous diet. A recent (this year) study found that Basilosaurus had an estimated bite force of 3,600 pounds, giving it the strongest jaws of any mammal yet measured.

FEA analysis of a Basilosaurus skull. Snively et al. 2015. http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0118380

There is a bit of a problem saying how old Basilosaurus is. The original fossils from 1832, as were the Arkansas fossils, were found in the Jackson Group, a series of intertidal to estuarine and shallow marine sediments of Eocene age, around 37-34 Mya. Another set of fossils from Crowley’s Ridge was found in 2008. However, according to marine mammal biochronology estimates, Basilosaurus should have appeared around 44 Mya. However, fossils do not generally record the first appearance of an organism. Thus, the most likely explanation is that Basilosaurus evolved roughly 7 My before the fossils we have found. The only way to solve this conundrum is to find more fossils, so get cracking.

Fossil Friday, A Whale of a Time

Were you able to figure out what the mystery fossil this week was?

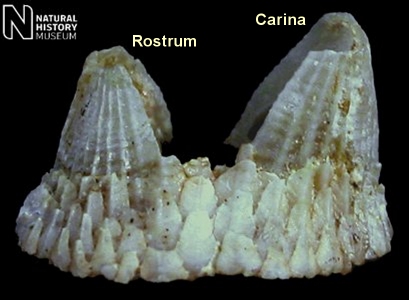

This is a vertebra, as I am sure most people could readily see. The two centra, the body of the vertebra, are flat to even a little concave, indicating an aquatic creature.

Here is a little more, showing pieces of the jaw.

Here is a picture by Karen Karr showing what the animal may have looked like when alive.

This is a Basilosaurus. The name means “king lizard”. It is an odd misnomer, though, because it is not a reptile at all. It is in fact a true whale, one of the first to have flippers rather than legs. Fossils of Basilosaurus have mostly been found in Alabama and a few other places in the southern United States, but the partial skeleton of one was found near Crowley’s Ridge in Arkansas.

An unexpected museum trip has presented itself to me, so this post will be short, but come back Monday for a more detailed discussion of Basilosaurus, the “bone crusher”.

Mystery Monday, Not a Fish Story

I have a new mystery fossil for you this week. I thought I would put a new fossil off until next week, but considering that next week is Spring Break for many around here and that new, cool research has been published on this animal recently, I decided to go ahead and put it out there.

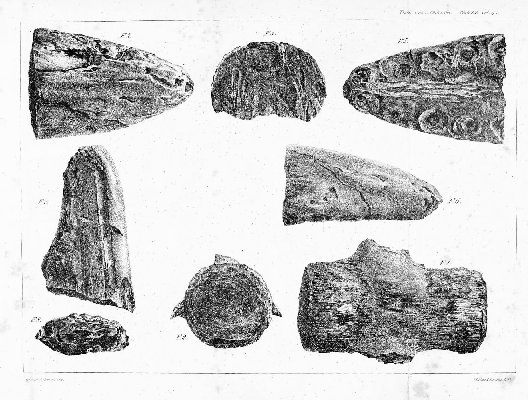

This is a drawing of the vertebra made by Sir Richard Owen, one of the greatest minds in paleontological taxonomy of the 19th century. The fossil had been identified as one thing, but Dr. Owen provided a thorough and convincing discussion of why that interpretation was wrong. The name given to it was rather humorously coincidental, considering what it turned out to be. It is difficult to identify isolated vertebrae, so I’ll give you another drawing of the same animal, but different parts.

This image is by the person who originally described the earlier vertebra, but also includes a few more pieces.

See if you can take the images, along with my clues, and figure out what this is. We’ll see if anyone can do better than the original descriptor.