Home » Posts tagged 'Arkansas' (Page 4)

Tag Archives: Arkansas

The First Mystery Monday of 2015

Time for the first mystery fossil for the year. Can you figure out what this humble little sphere is? Specimens of these little fellows have been around for over 500 million years, but I bet you have a reasonable facsimile in your house.

Leave your thoughts in the comments section and come back Friday for the answer.

Mr. Ed’s Fossil Friday

Next week is Christmas, Hanukkah started this week, there is Boxing Day, Yule, Kwanzaa, even Festivus and Hogswatch, not to mention the old classic Saturnalia and a whole host of others. Busy week for those wanting to celebrate. In honor of that, I came as close as Arkansas fossils allow to a well-known, traditional, seasonally-associated animal. Were you able to figure it out?

If you guessed reindeer, you were wrong. Sadly, there is no record of reindeer ever having lived in Arkansas that I can find. If there were, I would have used it. So no skeletons of Rudolph for us. The closest thing to a reindeer that has been found in Arkansas are fossils of the common white-tailed deer, which is so common in the state that it not infrequently becomes one with motor vehicles, much to the dismay of both deer and driver.

So what could this be besides a deer, reined or not? Reindeer are in the genus Rangifer, which are in the family Cervidae, along with deer. Cervids are artiodactyls, mammals best known for having cloven hoofs, thus the term “even-toed ungulate.” Unfortunately, Arkansas is not really known for artiodactyls either, other than pigs, and somehow, pigs did not seem an appropriate holiday animal. So what to do?

There is another animal that is often associated with the holidays, especially in the Christmas tradition, that being the donkey. I am sure you’ve heard of the story of Joseph leading a donkey upon which rode Mary to Bethelem and what Nativity scene is complete without a donkey? Donkeys, of course, are in the same genus as the horse, Equus, which are perissodactyls, the odd-toed ungulates. So allow me to introduce you to Scott’s Horse, Equus scotti, named after the paleontologist William Berryman Scott, a Princeton paleontologist known for his work on Cenozoic mammals.

Almost everyone is familiar with horses today. They stand as an iconic symbol of the Wild West, an integral image of the American cowboy and the Native Americans that roamed through the plains. Horses are also one of the most commonly used examples of evolution, with the line from Hyracotherium to Equus in virtually every evolution textbook ever written. All the discussions talk about how they got bigger and lost most of their toes as adaptations for running, and grew higher-crowned teeth to deal with the tough grasses they started to eat that replaced the softer, lush forest plants.

McFadden, Bruce. 2005. “Fossil Horses – Evidence of Evolution.” Science Vol. 307. no. 5716, pp. 1728 – 1730

What is less well known outside of those who study evolution and paleontology is that this process was not a straight chain from tiny, forest-dwelling horse ancestor to the modern horse. The horse lineage diversified, evolving into multiple niches. This shouldn’t really be too much of a surprise, considering the diversity seen in horses today, with everything from burros and Shetland ponies to Clydesdales and zebras. Most of them died out before the modern horses we see today arrived. Scott’s horse was one of these extinct forms.

Another thing that is not well known outside of paleontologists is that the modern horse originated in North America, but are not the ones living here today. Horses evolved during the Pliocene, five million years ago. Adaptations allowed them to survive the change from forests to more open, grassy plains, driving their evolution. From North America, they spread into South America through Central America and into Asia and Europe across the Bering land bridge. The Bering Sea Straits were dry at this time because the ice ages during the Pleistocene lowered water levels, allowing passage between the continents. Horses, along with many other animals, like mammoths and camels (also originally American), crossed through the land bridge to populate lands on either side.

Another thing that is not well known outside of paleontologists is that the modern horse originated in North America, but are not the ones living here today. Horses evolved during the Pliocene, five million years ago. Adaptations allowed them to survive the change from forests to more open, grassy plains, driving their evolution. From North America, they spread into South America through Central America and into Asia and Europe across the Bering land bridge. The Bering Sea Straits were dry at this time because the ice ages during the Pleistocene lowered water levels, allowing passage between the continents. Horses, along with many other animals, like mammoths and camels (also originally American), crossed through the land bridge to populate lands on either side.

At the end of the ice ages about 11,000 years ago, every species of the American horse, including E. scotti, died out, along with all of the other megafauna. Horses continued to thrive in South America and Eurasia, but for over 10,000 years, their North American homeland was barren of horses. It was not until the Spanish conquistadors brought them back that horses once again thrived in North America. Thus, we can thank the Spanish for bringing back a quintessentially American product.

Mystery Monday, Happy Holidays

This will be the last mystery fossil for the year. After this, I, like hopefully everyone else, will be enjoying the holidays. Arkansas does not have any fossils that are terribly well associated with any of the late December holidays, but I got as close to one as I could. It is closely related to animals living here today, but it died out long before its modern relative was reintroduced. Put your guesses in the comments section and check back Friday for the answer.

It’s a Bird! It’s a Fossil Friday

Were you able to figure out what this ancient skull belonged to?

It looks for all the world like a bird, but birds don’t have teeth, do they?

Certainly not now, but early in avian history, they did. Teeth are but one of the many pieces of evidence that connects them to theropod dinosaurs like Velociraptor and Deinonychus. This particular bird was named Hesperornis regalis, the “royal western bird”. It lived in the Late Cretaceous, at the same time as such famous dinosaurs as Tyrannosaurus rex and Triceratops and marine reptiles like mosasaurs and elasmosaurs.

Grebes and loons. Studer’s Popular Ornithology: The Birds of North America. Jacob H. Studer, with illustrations by Theodore Jasper (1878)

The picture of the skull above was published by Othniel Marsh in 1880. The skeleton Marsh described and several other specimens show that Hesperornis was a diving bird, much like grebes, loons, and some rails and cormorants. Like the flightless cormorant, Hesperornis had very small wings and lacked the ability to fly. Some diving birds, like penguins, use their wings to “fly” through the water, but Hesperornis, like its modern counterparts, used their feet to propel themselves. Its feet were likely lobed, like grebes, rather than fully webbed like most aquatic birds.

Hesperornis showing jaw feathers. http://oceansofkansas.com/hesperornis.html

Hesperornis was a large bird, standing close to a meter (3 feet) tall and 1.8 meters (6 feet) in length. Its beak was long and pointed, with teeth on its maxilla and all but the tip of the mandible, or lower jaw. According to work by Tobin Hieronymus, the parts of the jaws with teeth were covered in feathers, with keratin covering the toothless portions. It lived in coastal waters, diving for fish and trying to avoid the aquatic reptiles that were the apex predators of the time.

In Arkansas, Hesperornis has been reported from the Ozan Formation in Hempstead County, a series of mostly sandy, limey mudstone, typical of warm coastal marine areas. As one would expect, given Hesperornis‘s aquatic nature, all the other fossils found with it represent marine animals, including sharks, bony fish, turtles, mosasaurs, and pliosaurs. During the Late Cretaceous, when these sediments were deposited, southwest Arkansas was at the eastern edge of the Western Interior Seaway, a marine environment created by high sea levels that flooded much of the central United States.

This find represents the southernmost extent of Hesperornis’s range, which extended up into the Arctic. It was a lot warmer then, but still cold at the poles. It should be kept in mind though, that the find consists of one partial bone, the left tarsometatarsus, part of the lower leg. It is easily recognizable as avian and has been identified as Hesperornis due to its age and size, although Dr. Larry Martin stated it could be a new taxon. We will just have to wait until more fossls turn up to know for sure. Parts of the Ozan Formation are quite fossiliferous, so there is a chance that more will be found.

The After Thanksgiving Mystery Monday

I hope you had a Happy thanksgiving, filled with all the food and family you could stand. Get back into the swing of things (before you take another break for Christmas) with another Mystery Monday fossil. Here’s a hint to get you going: while it may pose a passing resemblance to a modern animal, this one hasn’t lived since dinosaurs were walking around Arkansas. Come back Friday for the answer.

Fossil Friday, it’s a crabby day

Were you able to figure it out? Congratulations to Showmerockhounds for getting it right.

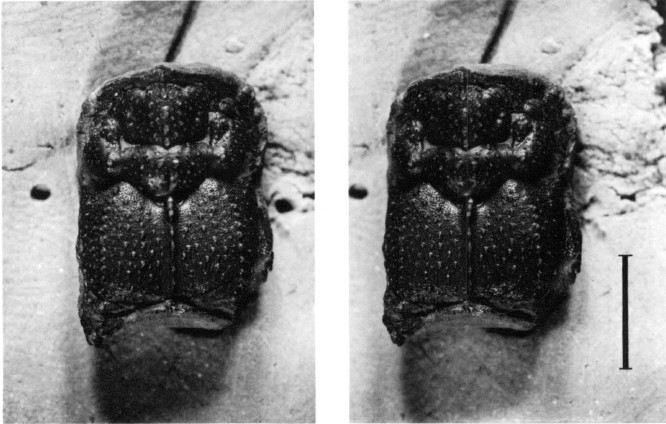

This picture shows the carapace of a decapod crustacean, the group that includes crabs, crayfish, lobsters, and shrimp. More specifically, it is Imocaris tuberuculata, a crab generally considered to be in the group Dromiacea, within Brachyura. The name means crab from the Imo Formation, which is where it was found by Frederick Schram and Royal Mapes in a roadcut along I-65 near Leslie, AR. The rocks around Leslie are a great place to hunt for invertebrate fossils, numerous specimens have come from there. Imocaris is very rare, but quite distinctive, with a carapace that looks like a frog-headed bodybuilder wearing enormous sequined parachute pants.

Fuxianahuia. 520-million-year-old crustacean with a heart. https://www.sciencenews.org/article/ancient-crustacean-had-elaborate-heart

Imocaris is an intriguing fossil in that the Imo Formation is thought to be Carboniferous in age, in the Upper Mississippian Period roughly 320-330 million years old. Even though the fossil record of decapods goes back to the Devonian Period, few exist in the Paleozoic, not really hitting their stride until the Mesozoic Era. The fossil record of crustaceans as a whole go all the way back to the Middle Cambrian over 500 million years ago, with specimens found in the Burgess Shale. Thus, the true origin of the crustaceans must be even earlier than that, probably some time in the early Cambrian or the Ediacaran, the latest stage of the preCambrian Era.

The contact (black line) between the Pitkin Limestone (above) and the Fayetteville Shale (below) along highway 65 near Marshall. Arkansas Geological Survey.

The Arkansas Geological Survey calls the Imo Formation as a member of the Pitkin Limestone Formation. The Imo is a shale layer interspersed with thin sandstone and limestone layers found nearthe top of the Pitkin Formation. The Imo, and the Ptikin in general, demonstrate a shallow marine environment indicated by the limestone and an abundance of marine fossils. Most of the fossils are invertebrates showing off a thriving coral reef system, but you can also find conodonts and shark teeth as well. The Pitkin Limestone sits on top of the Fayetteville Shale, itself well known for fossils, particularly cephalopods. The boundary between the two can be seen along I-65 closer to Marshall.

Mystery Monday

If the cold and the ice (or lack of ice for those of you hoping for a day off from school) has gotten you in a bad mood, see if you can distract yourself with solving this week’s mystery fossil. This week I am presenting something totally unlike anything I have presented before. The scale bar in the photo is 5 mm.

Last Week’s Mystery Monday Revealed: Getting to the Root of the Problem

Were you able to figure out last Monday’s mystery fossil? For a reminder, here it is again.

Were you able to figure out last Monday’s mystery fossil? For a reminder, here it is again.

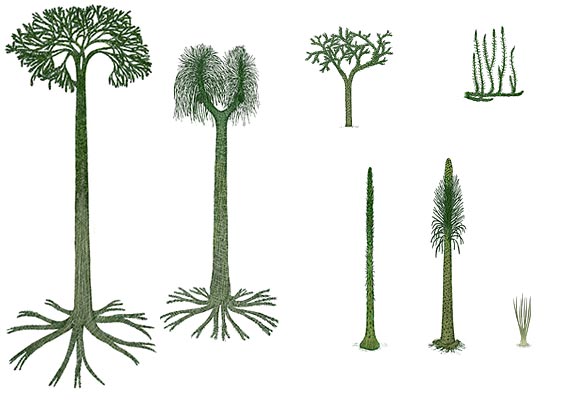

Two people correctly identified it as a plant fossil. While both guesses were fossils that are found in Arkansas in similar places and times, the Natural Historian identified this as a Stigmaria. Technically, Stigmaria is a “form taxon”, meaning that it is named for the shape and not the actual organism, but in general, the only ones that really get called Stigmaria are root casts of lycopsid trees. The two main ones are Sigilaria and Lepidodendron. This particular one is Lepidodendron, which is the typical one found in Arkansas.

Lycopsids like Lepidodendron lived during the Carboniferous Period from about 300 to 360 million years ago, so named because this was the time of extensive coal swamps. Coal swamps, as the name suggests, were responsible for most of the coal we find. During this time, organisms capable of digesting lignin, a chief component of wood, had not yet evolved and spread sufficiently to make a dent in the decaying logs. Lignin is a tough fiber, so without organisms capable of breaking it down, it tended to last for a long time, so decaying plant matter built up, eventually being compressed into coal. Genetic studies indicate that the enzyme to digest lignin first appeared around 300 million years ago, which likely not coincidentally marks the beginning of the end for coal swamps, which by and large died out in the Permian Period, not long after the end of the Carboniferous.

Image by Dennis Murphy. http://www.devoniantimes.org/who/pages/lycopsid.html

Lycopsids today include the quillworts, spike mosses, and club mosses, although Lepidodendron is most closely related to the quillworts. Today, these plants are small and serve mostly as ground cover. In the Carboniferous, they formed towering trees reaching over 40 m tall (just for comparison, the average oak tree is no more than 20 m, although they can get up to 30 m tall). They also grew very quickly, reaching maturity in only a few years, which likely also contributed to the massive buildup of decaying plant matter. Lepidodendron literally means “scale tree”, so called for their scaly appearance. They have occasionally been mistaken for fossils of snake or lizard skin. Personally, they remind me of giant pineapples.

Lepidodendron can be found in most of the Pennsylvanian age rocks in Arkansas, although the most common place is in the upper Atoka Formation in the Boston Mountains and the Arkansas River Valley through the northern section of the Quachitas. The Atoka Formation is a series that represents deep marine sediments at the base of the formation gradually turning into deltaic deposits in the upper sections. There are several layers of coal, coally shale, and oil shale. I have even seen a few spots in which the amount of oil in the shale is enough to smell it and the rock can catch fire. This region has not been extensively used by the coal and oil industries because it is prohibitively expensive to extract the oil from the shale and the coal is high in sulfur, making it less than optimal for use. But if you are looking for plant fossils in Arkansas, it is the place to go.

Mystery Monday

Halloween is over, time to get back to work for a few weeks before we take off for Thanksgiving. To get your brain back into gear after eating all that candy and waking up from sleeping like a log in your sugar coma, can you figure out what this week’s fossil is?

Check back in next Monday for the answer. I will be at a conference on Thursday and Friday and will likely not be able to post an answer until after the conference is over. Or you can check the Facebook page for a quicker answer.

Check back in next Monday for the answer. I will be at a conference on Thursday and Friday and will likely not be able to post an answer until after the conference is over. Or you can check the Facebook page for a quicker answer.

Mysteries Revealed at a Slothful Pace

What happened to revealing the answer on Friday, you ask? If you follow the Paleoaerie Facebook feed, the answer was given there. Sadly, unexpected illness (as if one can schedule being sick) delayed me from getting a more complete post on the blog. Thus Fossil Friday has preempted Mystery Monday.

With that being said, were you able to figure out what this was?

If you thought they looked like teeth, you are quite right. But the chisel-like teeth are rather peculiar. To give some sense of scale, the teeth are roughly 10 cm long and 3 cm wide. So they are not small. They are hypsodont, meaning high-crowned, like that seen in the molars of horses, which is a good indication of herbivory. The cusps are simple, with only two cusps, unlike that seen in horses and other mammalian herbivores and totally unlike anything seen outside of Mammalia. The teeth are distinctive for particular group of animals, those known as sloths.

No, not that type. These teeth belonged to a giant ground sloth. Unlike their modern cousins, giant ground sloths are so named because they lived on the ground rather than in the trees and were very large, capable of standing upwards of 6 m (20 feet) high and weighing, depending on who you ask, 6-8 tons. Ones of this size are known as Megatherium and are commonly found in the La Brea Tar Pits, although they ranged throughout the Americas. The ones found in Arkansas are of the genus Megalonyx (“Great Claw”) were somewhat smaller than Megatherium, only about half the size of its larger kin, and ranged throughout North America.

Megalonyx jeffersonii, or Jefferson’s Ground Sloth, was so named because Thomas Jefferson gave a lecture on this animal in 1797 which is sometimes said to have marked the start of vertebrate paleontology in the United States.

Great American Interchange. Richard Cown http://mygeologypage.ucdavis.edu/cowen/

Giant ground sloths, as a group, originated in South America about 35 million years ago and made their way into North America during the Great American Interchange about 8-9 million years ago (this is often not considered to start until about 3 million years ago, but fossil evidence indicates at least some organisms began the march between the continents much earlier). The Great American Interchange was so named because this marked the time that North and South America became joined, creating a wide corridor through which many plants and animals passed. Interestingly, ground sloths were unusual in that they migrated northward. Most animals migrated south from North America. This was most likely due to the fact that Central America at the time was mostly scrubland, whereas the northern part of South America was covered in lush forests. This meant that those on the southern continent had little incentive to leave. The North American animals, on the other hand, were in areas of limited resources and would have viewed the abundant resources in the south as highly enticing.

Xenarthran joint. Dr. Kaci Thomspon. http://www.life.umd.edu/classroom/bsci338m/Lectures/Xenarthra.html

Another animal that went north during this time was one well known to many people in the southern Midwest, the armadillo. Interestingly, both sloths and armadillos are in the group called Xenarthrans, so-called for an extra articulation in the vertebra. Xenarthrans include sloths, armadillos, anteaters, and an interesting animal called a glyptodont, the mammalian equivalent to the ankylosaur. It had a bony carapace, a tail club, and was the size of a subcompact car. For some reason, the xenarthrans were far more successful moving north than almost any other animal, with the main exception of the giant, flightless terror birds in the group Phorusrachidae, such as Titanis, a bird towering 2.5 m (8 feet) or more tall.

Giant ground sloths lived in a variety of environments, ranging from arid savannas to jungles. Most of them, like Megalonyx, appear to have preferred lush forests along rivers and lakes.

I will end this with a statement of the end of the giant ground sloths. What drove them to extinction? They went extinct 10-12,000 years ago, at the end of the last ice age. This was also shortly after the arrival of humans, who, evidence suggests, hunted them on a regular basis. As large, slow-moving herbivores, they made for easy prey. Unlike other predators, humans could easily avoid the sharp claws and powerful forelimbs of the sloths by attacking with spears. Was it climate change or human overhunting, known as the overkill hypothesis? Many researchers fall on the side of human overkill due to the fact that the sloths had survived several similar periods of climate change without issue and the pattern of extinctions globally does not match well with local climate changes. However, others claim climate change due to the loss of plant diversity after the last ice age, which was not seen in the previous climatic shifts. Which is correct? Perhaps the answer is both. It is not unreasonable to think that the climate change lowered population levels, which ordinarily would have been survivable, but the added pressure of human hunting proved an insurmountable challenge.