Home » Posts tagged 'fossil' (Page 8)

Tag Archives: fossil

Fossil Friday, Revenge of the Serpent

Mystery Monday this week fell on St. Patrick’s Day, so to celebrate, the following image was posted for the mystery fossil of the week.

St. Patrick was well known for driving all the snakes from Ireland, at least so the myth goes. In reality, there never were any snakes in Ireland for St. Patrick to drive out in the first place. But unlike Ireland, Arkansas has always had snakes. Right now, we have a diverse population of snakes, including boasting more different types of venomous snakes than most other states, being one of only ten states that have all four types of venomous snakes in the country (there are roughly twenty separate species, but they all fall into four main groups). Here you may find the copperhead, coral snake , cottonmouth (aka water moccasin), and the rattlesnake (including the Timber, Western Diamondback, and pygmy rattlers). At least we can take comfort that we are just outside the ranges of the Massasauga and Eastern Diamondback rattlesnakes and we don’t have the diversity of rattlers seen in places like Arizona and Texas (which may win the prize for most venomous snakes in the country if both species number and diversity are taken into account).

St. Patrick was well known for driving all the snakes from Ireland, at least so the myth goes. In reality, there never were any snakes in Ireland for St. Patrick to drive out in the first place. But unlike Ireland, Arkansas has always had snakes. Right now, we have a diverse population of snakes, including boasting more different types of venomous snakes than most other states, being one of only ten states that have all four types of venomous snakes in the country (there are roughly twenty separate species, but they all fall into four main groups). Here you may find the copperhead, coral snake , cottonmouth (aka water moccasin), and the rattlesnake (including the Timber, Western Diamondback, and pygmy rattlers). At least we can take comfort that we are just outside the ranges of the Massasauga and Eastern Diamondback rattlesnakes and we don’t have the diversity of rattlers seen in places like Arizona and Texas (which may win the prize for most venomous snakes in the country if both species number and diversity are taken into account).

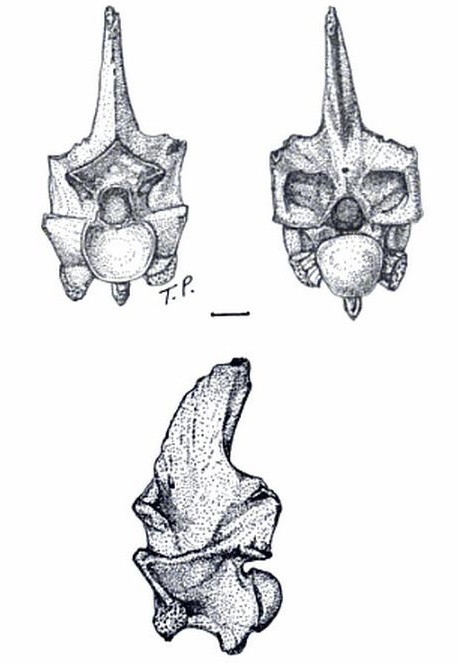

In the past though, we also had other snakes, including Pterosphenus schucherti, also known as the Choctaw Giant Aquatic Snake, a giant sea snake that lived here in the late Eocene roughly 35 million years ago. The Eocene was a much warmer time. In fact, this period falls at the end of what is called the Palaeocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum. There were no polar ice caps during this time, with at least double the amount of carbon dioxide and triple the amount of methane than what we see now. Because of this, Louisiana was pretty much under water and Arkansas had wonderful ocean front property, along with a lot of swamps and marshes. It is likely the cooling during this period into the Oligocene Period, that caused the extinction event that wiped out these snakes, along with several terrestrial mammals, including a variety of Perissodactyl horse ancestors, artiodactyls (cloven hoffed mammals), rodents, and primates.

Pterosphenus model at the Florida Museum of Natural History. It is too wide, though, as noted by the staff of the VMNH paleontology lab, who took this picture.

This was the perfect environment for a number of different snakes, although we don’t have fossil evidence of many. One that we do have is of Pterosphenus. This snake had tall, narrow vertebrae, indicating adaptation to an aquatic lifestyle. In fact, it probably was not able to support itself on land very well due to its thin body.

Little file snake, Acrochordus granulatus. http://www.markshea.info

Sea snakes today rate as some of the most highly venomous snakes in the world. However, there are nonvenomous ones as well, such as the marine file snake, Acrochordus granulatus, which live in coastal regions between Asia and Australia. Those of today are relatively small snakes, ranging from half a meter to just over 2 meters (2 feet to 7 feet or so). Pterosphenus, on the other hand, reached lengths of 2.3 m to 5.1 m, or possibly larger.

Unfortunately, we don’t know a whole lot about these snakes, other than they were clearly aquatic. The bones that have been found with them, such as whale bones, have indicated marine waters. Fossils of these snakes have been found in eastern Arkansas, in Saint Francis County in the Eocene deposits around Crow Creek called the Jackson Group.

Mystery Monday

It’s Monday! Time for a new mystery fossil. See if you can guess what this is. Don’t clam up, put your guess in the comments below.

Mystery Monday, another snow time edition

I don’t know where you may be, but where I am, ice is covering everything and all the schools are closed. It’s a great day to pull up the covers and stay under the blankets, maybe get a cup of hot chocolate and wait for warmer weather. That makes today’s Mystery Monday fossil particularly apropos. Yes, this really is a fossil, not just layers of sediment.

Fossil Friday! The Red-faced Fossil

Between classes and school appearances, I have not had the time to write up as complete a description as I would like, so I will do a more complete description of the fossil later. But for now, did any of you think you saw crinoids in the face? If you did, you are correct! This photo was originally published on the Arkansas Geological Survey‘s blog. If you haven’t checked them out, I encourage you to do so.

Crinoids are perhaps the most common fossil found in Arkansas. They can be found in many of the Paleozoic rocks in northern Arkansas in the Ozarks and Ouachitas, although they are most common in the Mississippian age limestones of the Ozarks. All those white rocks along Highway 65 towards Leslie and Marshall are good candidates, although watch out for cars along the highway, please.

Stellar examples of crinoids in all their fossilized glory. This image and more information can be found at http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/echinodermata/crinoidea.html

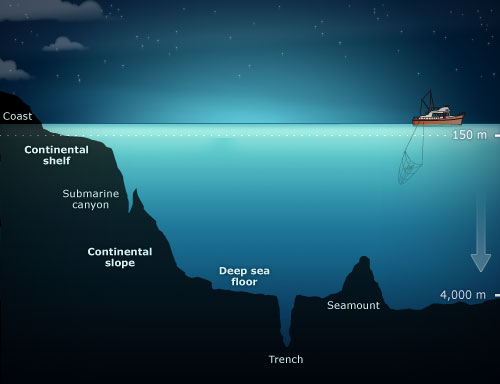

Crinoids are often called sea lilies because of their resemblance to plants, but they are actually animals that are related to sea urchins and starfish, so they are far more closely related to you than to any plant. Even though they lived in shallow marine environments during the Paleozoic Era, you can still find them today in deep water along what is called the continental slope. If you swim out into the deep water a long way away from shore and you get to the edge of the continent, you will see a cliff or steep slope descending all the way down to the abyss of the absolute bottom of the ocean. Congratulations, you have reached the continental slope and the last refuge of the crinoids.

Mystery Monday! Can you identify the fossils in the face?

It’s another Monday! You know what that means, right? The end of the weekend, an extra dose of coffee to get the day started, and a new fossil for Mystery Monday. Today’s fossil is a very common fossil in Arkansas. Some people think these fossils form a kind of spooky face. Bonus points if you can say where the picture came from. Once I tell you what it is, you should check out all the other cool info they have.

Fossil Friday! Today we’re being a stick in the mud.

On Monday, we posted this picture of an Arkansas fossil. Were you able to figure it out?

This is a fossil of Calamites (watch your spelling, we want to avoid any calamities). Calamites was a relative of the modern-day horsetails, Equisetum. But unlike today’s horsetails, which are generally only a meter or so in height (although some giant horsetails can grow up to 7 meters or more), Calamites grew up to 30 meters (100 feet).

Equiseta often grow clonally, spreading the rhizomes widely through the surrounding ground, forming large clumps of plants that are essentially the same plant, connected via their roots. Assuming Calamites did the same thing, it has been estimated “they may have been the largest organisms that ever lived.” This group of plants is unique in the incorporation of silica into their stems, giving rise to one of their common names being scouring rushes.

This group of plants first appeared in the late Devonian, but really had their heyday in the Carboniferous Period, although they died out soon after in the Permian. The Carboniferous is so named because most of the world’s coal was formed during this time. The reason for this is because of the difficulty in digesting plant matter. Cellulose, the primary ingredient in plant cell walls and what we call “dietary fiber.” Even today, other than fungi and some bacteria, there is precious little that can break it down. Lignin, the other main component of plant cells walls, otherwise known as “wood,” is even harder to break down.

And they think they have a termite problem. http://www.ces.ncsu.edu

The only thing that can really digest it is white rot fungi. Back then, there was little to nothing that could eat it. As a result, dead plant matter tended to sit around for a very long time, making it much more likely to accumulate and form coal. Once the enzymes needed to break down lignin evolved, white rot fungi found themselves with a hugely abundant food supply and acted like teenaged football players after a game at an all-you can-eat buffet. And thus ended the Carboniferous Period, in a massive bout of white rot.

Like modern horsetails, Calamites preferred wet soils around rivers and lakes, cropping up all over the world. While they avoided the standing water of the swamps, they flourished any place that regularly got wet, so levees and floodplains were good environments for them. There were no angiosperm trees at that time, what was there were forests of giant Calamites and ferns. Plants called lycopods, most commonly Lepidodendron, dominated the swamps along with the ferns, which were pretty ubiquitous.

Calamites landscape. Illustration by Walter Myers, http://www.arcadiastreet.com

Calamites’ modern counterparts are all herbaceous perennials, so Calamites is unique in the group for having a woody trunk. They form extensive underground rhizome networks, growing large clumps of clones from the rhizomes. The leaves form regularly spaced whorls around the stem, creating the horizontal lines breaking up the ridges running vertically up the trunk on Calamites. Inside, the xylem forms rays running from the exterior to the pith in the center. Oftentimes, the pith rots away, leaving a cavity that gets filled with sediment, forming an internal cast, or steinkern.

As a plant fossil, anyone can legally collect Calamites fossils as long as they are not on National Forest property (nothing is allowed to be collected in National Parks and Forests). Good places to look for Calamites would be among the Pennsylvanian (Late Carboniferous) rocks in the Quachitas and Ozarks. While Calamites may be found in rocks of Mississippian (Early Carboniferous) age, the rocks in Arkansas from that age are primarily marine. Good for finding sea shells, but land plants like Calamites are going to be rare, only there as a result of being washed in by a storm or some such. You will be much more likely to find them in rocks like the Atoka Formation on both sides of the Arkansas River Valley. Most of the Ozarks is Mississippian, but much of the Ouachitas is Pennsylvanian, so are much more likely to have them. You might find them in the Hartshorne sandstone (seen best capping Petit Jean Mountain), but plant fossils are rare and fragmentary. You would have better luck in the McAlester Formation overlying the Hartshorne. You can also try the Savanna and Boggy Formations, which are also of Pennsylvanian age.

Mystery Monday!

It’s time for Mystery Monday! Here is a fossil that can be found in Arkansas, but is completely different from anything I’ve put up here before. Let’s see if you have the paleontological fiber needed to solve this puzzle, or do you lack the stomach for it? 🙂

Mystery Monday, snow edition

The weather forecast this week is for snow. So in going with the theme lately of Ice Age animals, I thought I would bring you another one for this week’s Mystery Monday fossil. This picture doesn’t have a scale, so I will just say this skull is bigger than yours (under the assumption that all my readers are Homo sapiens or within the same size range, my apologies to the exceptionally macrocephalic).

Fossil Friday, a fossil of not quite mammoth proportions

It’s time to reveal the answer to Monday’s Mystery Fossil. We had three people who correctly identified this as the skull of Mammut americanum, the American Mastodon.

It’s time to reveal the answer to Monday’s Mystery Fossil. We had three people who correctly identified this as the skull of Mammut americanum, the American Mastodon.

Mastodon bones have been found throughout Arkansas, although almost all have been found either in northeast Arkansas between Crowley’s Ridge and the Mississippi River or along the Red River in Southwest Arkansas. According to the Arkansas State University Museum in Jonesboro, Arkansas has more mastodon finds than any other state in the mid-south region, with at least 20 different skeletons. Most of the work on them has been done by Dr. Frank Schambach and others of the Arkansas Archaeological Survey, headquartered at the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville, along with members of the Arkansas State University Museum. This particular mastodon was excavated by Dr. Schambach with the help of the Arkansas Archaeological Society along the Red River in Southwest Arkansas, I think in 1987, although I am not sure of the date yet.

Mastodons were related to elephants, although not as closely related to modern elephants as mammoths. Mammoths have also been found in Arkansas, most notably the Hazen mammoth, found in 1965. That specimen was a Columbian mammoth (Mammuthus columbi), a less hairy version of the wooly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius). They lived across much of North and Central America during the Miocene and Pliocene, although they are known mostly from the Pleistocene in Arkansas, the heyday of the Ice Age, which is when people traditionally think of them living. They were similar in size to modern elephants.

The teeth of mastodons, mammoths and modern elephants tell an interesting story. Modern elephants have a wide diet of vegetation from grass to fruit and tree limbs. The Asian elephant has teeth that are more plate-like in form, making a series of ridges that create an excellent grinding surface. African elephants spend more time in forests and bush lands, with a corresponding higher amount of bushy vegetation in their diet. Their teeth are large, multi-rooted teeth with a series of ridge-like cusps. Mammoths take the plate-like grinding surface to an extreme as an adaptation to the grasslands they frequented. Mastodons, on the other hand, specialized in the opposite direction, with large, prominent cusps suited to a more forested environment and diet. Thus, mastodons and mammoths formed a bracket surrounding elephant ecology.

Mastodon (left), Mammoth (right). http://www.igsb.uiowa.edu/

Work that has recently come out has shed new light on why they went extinct. People have long argued over whether climate change or humans wiped out the megaherbivores at the end of the last ice age. The Overkill hypothesis postulated that early humans hunted them to extinction. There is also the alternative that other actions by early humans contributed to their extinction. However, while there has been plenty of evidence indicating humans did hunt mammoths (e.g. the Clovis people at the Dent site in Colorado), the hypothesis has come under fire for the lack of widespread hunting evidence and timing issues, with research indicating the megaherbivores were already going extinct before humans appeared on the scene. The other hypothesis, climate change, has gotten more support from a study of plant fossils. According to the new data, the early tundra environments were dominated, not by grass, but by forbs, weedy herbaceous plants with more nutrients than grasses. An earlier glaciation 20-25,000 years ago dramatically reduced the abundance of these plants. When the weather warmed up, the forbs increased again, but never approached their previous levels. When the next glaciation hit, the forbs mostly died out, allowing the less nutritious grasses to take over, which greatly reduced the amount of herbivores the land could support. Of course, this does not mean that humans had nothing to do with the extinctions, but it does mean they were likely not the primary cause, more likely simply throwing the last spear into the coffin of the great herbivores.

That’s it for this week. Check back Monday for a new mystery fossil. Have a good weekend.

You found a fossil… now what? (all the details!)

One of the questions I get often is what should you do if you find a fossil. I have been meaning to write a post discussing that, but I found that someone else had already written a very nice discussion on that very topic. I thought why duplicate the efforts of someone else who has done a fine job already? So instead of writing my own post, I am just going to refer you to their blog post. So without further ado, may I present…