Home » Paleontology » Fossils of Arkansas (Page 4)

Category Archives: Fossils of Arkansas

Website Full of Fossils

Southwest Arkansas has a lot of Cretaceous rocks. During that time, Arkansas was right at the border of the Western Interior Seaway. As such, one can find a lot of marine fossils from the dinosaur era, including mosasaurs, elasmosaurs, oysters by the millions, clams, shark teeth, and much more. You can also find shoreline fossils, such as thousands of dinosaur footprints and the occasional bone.

If one crosses the border into North Texas, one can find a lot of fossils that are similar to the southwest Arkansas marine fossils. There is a website, called txfossils.com, a Texas resident has put up showing lots of pictures of the fossils found in the area. The pictures are divided into several categories. The first category is for cephalopods, which are mostly ammonoids. They are listed as ammonites, but they are mostly goniatites from what I can tell, although I can not see the suture patterns (the septa, or walls, between body chambers) well enough and most of them to say for sure. Even though most people refer to the entire group as ammonites, ammonites comprise a single subgroup with the larger group called ammonoids known for complex body septa. Goniatites have a simpler wavy pattern. Nautiloids comprise the third group and are known for simple curves forming the septa.

If one crosses the border into North Texas, one can find a lot of fossils that are similar to the southwest Arkansas marine fossils. There is a website, called txfossils.com, a Texas resident has put up showing lots of pictures of the fossils found in the area. The pictures are divided into several categories. The first category is for cephalopods, which are mostly ammonoids. They are listed as ammonites, but they are mostly goniatites from what I can tell, although I can not see the suture patterns (the septa, or walls, between body chambers) well enough and most of them to say for sure. Even though most people refer to the entire group as ammonites, ammonites comprise a single subgroup with the larger group called ammonoids known for complex body septa. Goniatites have a simpler wavy pattern. Nautiloids comprise the third group and are known for simple curves forming the septa.

The other categories include gastropods (snails), echinoids (sea urchins), bivalves (clams), coral and bryozoa, petrified wood plants, and bones from vertebrates. The vertebrate bones include a varitey of shark teeth and some teeth from Enchodus, the “fanged herring”. There are also what appear to be turtle shell fragments and some random bits of bone I cannot identify.

The other categories include gastropods (snails), echinoids (sea urchins), bivalves (clams), coral and bryozoa, petrified wood plants, and bones from vertebrates. The vertebrate bones include a varitey of shark teeth and some teeth from Enchodus, the “fanged herring”. There are also what appear to be turtle shell fragments and some random bits of bone I cannot identify.

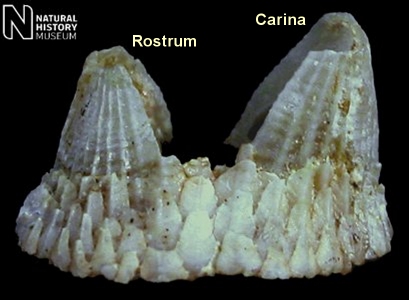

There are lots of pictures (the two shown here are from the website) which should give you some idea what you are looking at if you go fossil hunting in southwest Arkansas. Enjoy. As always, if you find any vertebrate material, please let me know. If you find invertebrate fossils you would like identified, your best bet is to contact Rene Shroat-Lewis at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock or Angela Chandler at the Arkansas Geological Survey.

Mystery Revealed: A Common Coral in Arkansas

It is the unfortunate fact of life that volunteer efforts are all too often derailed by other pursuits. Such is the case for last week’s Mystery Monday fossil. Nevertheless, the answer shall be forthcoming. If you have been paying attention to the Facebook feed, you will know that the fossil presented last Monday was identified. Were you able to figure it out?

This is a large, very well preserved piece of tabulate coral. Corals are colonial species that are very important in modern ecosystems. A fourth of all ocean species live within these reefs. They form the backbone of reefs that are among the richer areas of biodiversity on the planet. Billions of dollars each year are pumped into local economies across the world.

What we think of as coral is mostly the calcareous homes they form, within which the animals live. The actual animal is a tiny animal in the Phylum Cnidaria. Cnidarians are soft-bodied animals, the best known of which are the jellyfish and sea anemone. Cnidarians take two general forms. Medusae are free-floating forms like the jellyfish. Coral and sea anemones are polyps, mostly stationary, or “sessile”, forms that remain in place their entire lives. Corals, like other cnidarians, are predatory, catching their prey with tentacles armed with nematocysts, cells containing potent poisons to immobilize or kill their prey. Of course, since corals are tiny creatures themselves, they prey on even tinier prey. The tentacles surround an opening which serves as both mouth and anus, basically making the animal a living, carnivorous sack. This is not the only way corals get food though. Most modern corals also have a symbiotic relationship with single-celled algae called zooxanthellae, which provide essential nutrients for the coral in which they live. Unfortunately, when the coral gets too stressed from increasing temperatures or other causes, they tend to respond by evicting the zooxanthellae. Because the zooxanthellae are what gives corals their bright colors, this is known as coral bleaching.

While there are several different kinds of coral, most of the coral people are familiar with are the stony corals, or Scleractinia, because these are the ones that build the reefs. They are part of the larger group of corals known as Hexacorallia (at least, if you are talking to modern biologists, paleontologists often restrict Hexacorallia to scleractinians), known for often having the individual coral homes partially divided with six partitions, or septa (although you may be hard pressed to identify the three axes forming the six partitions even if they are present in that number).

The scleractinians have only been around since the Mesozoic however. They did not build the coral reefs of the later Paleozoic Era. That distinction goes to the rugose, or horn, corals and the tabulate corals, such as the example above. Tabulate corals are known for the corals being aligned in horizontal stacks. The image above should really be rotated 90 degrees to get the life position. This stacking always reminds me of apartment building, particularly cheap tenement housing, or wire mesh. According to phylogenetic studies on modern corals, it appears that the earliest scleractinians did not have zooanthellae, the symbiotic relationship evolving later, so it seems likely tabulate corals didn’t either. Tabulate corals appeared in the Ordovician Period roughly 450 million years ago. They started dying out in the Permian and finally succumbed to extinction at the end of the Permian period 252 million years ago, along with most other life on the planet. However, it is a bit misleading to say they went extinct. It is thought that the modern scleractinians that arose in the early Triassic are descended from tabulate corals, so they appear to have evolved, rather than just died out.

If you want to find corals such as this in Arkansas, one need only travel anywhere in most of the northern part of the state. The Ozark Mountains are predominantly formed from shallow marine Paleozoic rocks. Anywhere you find limestone in the Ozarks, keep your eyes peeled for samples of this type of coral. They are invertebrates, so as long as you are not collecting in a National Forest or private property without the owner’s permission, you are free to collect them.

Fossil Friday. Soak up some information

Were you able to guess what the image was? It is a common animal almost everyone has at least a synthetic version of in their home. Yet they make terrible fossils.

Yes, this is a sponge. It is a small one, but typical for a fossil of a sponge. If they preserve well, they look like little balls, or pancakes (the squished ball sponge), or cylinders. All in all, visually very simple.

“Porifera body structures 01” by Philcha – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons – http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Porifera_body_structures_01.png#mediaviewer/File:Porifera_body_structures_01.png

Sponges belong to the the group called Porifera, so named because they have a lot of pores through which water flows through. Even though they may superficially look like some colonial organisms, they are true multicellular animals. Sponges have no true organs, or even tissues, but they do have specialized cells to handle various functions, such as reproduction, producing the materials needed for growing, and cells that act as a primitive immune system. The body organization is about as simple as you can get. Water flows through the pores into a central chamber, which has an opening at the top for water to flow out. As the water flows through, the sponge cells filter out nutrients, generally consisting of bacteria, plankton, and the occasional small animal, and excrete waste products.

Traditionally, sponges have been considered the most primitive of metozoans, the group comprising multicellular animals. There has been some research indicating that comb jellies are more primitive, but that work has been disputed by new research.

“92 ANM Glass sponge 2” by Randolph Femmer – National Biological Information Infrastructure 6259. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons – http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:92_ANM_Glass_sponge_2.jpg#mediaviewer/File:92_ANM_Glass_sponge_2.jpg

Sponges are normally divided into three different types. Demospongia is the largest of the three (although this may be because it includes sponges that may not be as closely related as typically thought). They form a “skeleton” out of small, pointed cylinders called spicules, made from either silica or a protein called “spongin”. The glass sponges, or Hexactinellid sponges, also make silica spicules, but these spicules are noticeably different from the demosponges. The third group of sponges make their spicules out of calcium carbonate and so are known as calcareous sponges. For more information on sponges, the wikipedia article is surprisingly good, so I will not belabor the points here.

It is these spicules that make fossils of sponges so problematic. When the sponges die, the soft tissues decay away and the spicules become little more than sand. Finding an intact fossil sponge is relatively rare. Thus, the vast majority of research done on fossil sponges is done through painstaking microscopic work on the spicules.

The fossil record of sponges goes back possibly as far back as 750 million years, although they do not become common until about 540 million years in the Cambrian and have been found all over the world. In Arkansas, the record of sponges is rather poor, mostly because very few people have worked on them and no one is looking for them. There are currently only four named fossil sponges and a few indeterminate sponge spicules.

Boring sponge, Cliona swpp. Photograph Forest Rohwer, San Diego State University. http://www.sms.si.edu/irlspec/Cliona_spp.htm

Demospongia is represented by three species. Haplistion sphaericum and Virgaspongia ichnata are demosponges found in the Bloyd Formation in Washington County. The Bloyd Formation is a Pennsylvanian aged formation found in the Ozark Mountains, a fossiliferous unit consisting of silty shale to massive sandstones, representing a relatively shallow marine environment with fluctuating sediment influx. Cliona, is a Late Cretaceous demosponge found in the Arkadelphia marl Formation in Hempstead County. Cliona is known as a boring sponge, not because it is uninteresting, but because it has a habit of boring holes into shells. This formation is mostly a limey mud best known for its mosasaurs, but also has a diverse assemblage of marine fossils. Stioderma hadra is the long glass sponge known from Arkansas and was also found in the Bloyd Formation.

The First Mystery Monday of 2015

Time for the first mystery fossil for the year. Can you figure out what this humble little sphere is? Specimens of these little fellows have been around for over 500 million years, but I bet you have a reasonable facsimile in your house.

Leave your thoughts in the comments section and come back Friday for the answer.

Mr. Ed’s Fossil Friday

Next week is Christmas, Hanukkah started this week, there is Boxing Day, Yule, Kwanzaa, even Festivus and Hogswatch, not to mention the old classic Saturnalia and a whole host of others. Busy week for those wanting to celebrate. In honor of that, I came as close as Arkansas fossils allow to a well-known, traditional, seasonally-associated animal. Were you able to figure it out?

If you guessed reindeer, you were wrong. Sadly, there is no record of reindeer ever having lived in Arkansas that I can find. If there were, I would have used it. So no skeletons of Rudolph for us. The closest thing to a reindeer that has been found in Arkansas are fossils of the common white-tailed deer, which is so common in the state that it not infrequently becomes one with motor vehicles, much to the dismay of both deer and driver.

So what could this be besides a deer, reined or not? Reindeer are in the genus Rangifer, which are in the family Cervidae, along with deer. Cervids are artiodactyls, mammals best known for having cloven hoofs, thus the term “even-toed ungulate.” Unfortunately, Arkansas is not really known for artiodactyls either, other than pigs, and somehow, pigs did not seem an appropriate holiday animal. So what to do?

There is another animal that is often associated with the holidays, especially in the Christmas tradition, that being the donkey. I am sure you’ve heard of the story of Joseph leading a donkey upon which rode Mary to Bethelem and what Nativity scene is complete without a donkey? Donkeys, of course, are in the same genus as the horse, Equus, which are perissodactyls, the odd-toed ungulates. So allow me to introduce you to Scott’s Horse, Equus scotti, named after the paleontologist William Berryman Scott, a Princeton paleontologist known for his work on Cenozoic mammals.

Almost everyone is familiar with horses today. They stand as an iconic symbol of the Wild West, an integral image of the American cowboy and the Native Americans that roamed through the plains. Horses are also one of the most commonly used examples of evolution, with the line from Hyracotherium to Equus in virtually every evolution textbook ever written. All the discussions talk about how they got bigger and lost most of their toes as adaptations for running, and grew higher-crowned teeth to deal with the tough grasses they started to eat that replaced the softer, lush forest plants.

McFadden, Bruce. 2005. “Fossil Horses – Evidence of Evolution.” Science Vol. 307. no. 5716, pp. 1728 – 1730

What is less well known outside of those who study evolution and paleontology is that this process was not a straight chain from tiny, forest-dwelling horse ancestor to the modern horse. The horse lineage diversified, evolving into multiple niches. This shouldn’t really be too much of a surprise, considering the diversity seen in horses today, with everything from burros and Shetland ponies to Clydesdales and zebras. Most of them died out before the modern horses we see today arrived. Scott’s horse was one of these extinct forms.

Another thing that is not well known outside of paleontologists is that the modern horse originated in North America, but are not the ones living here today. Horses evolved during the Pliocene, five million years ago. Adaptations allowed them to survive the change from forests to more open, grassy plains, driving their evolution. From North America, they spread into South America through Central America and into Asia and Europe across the Bering land bridge. The Bering Sea Straits were dry at this time because the ice ages during the Pleistocene lowered water levels, allowing passage between the continents. Horses, along with many other animals, like mammoths and camels (also originally American), crossed through the land bridge to populate lands on either side.

Another thing that is not well known outside of paleontologists is that the modern horse originated in North America, but are not the ones living here today. Horses evolved during the Pliocene, five million years ago. Adaptations allowed them to survive the change from forests to more open, grassy plains, driving their evolution. From North America, they spread into South America through Central America and into Asia and Europe across the Bering land bridge. The Bering Sea Straits were dry at this time because the ice ages during the Pleistocene lowered water levels, allowing passage between the continents. Horses, along with many other animals, like mammoths and camels (also originally American), crossed through the land bridge to populate lands on either side.

At the end of the ice ages about 11,000 years ago, every species of the American horse, including E. scotti, died out, along with all of the other megafauna. Horses continued to thrive in South America and Eurasia, but for over 10,000 years, their North American homeland was barren of horses. It was not until the Spanish conquistadors brought them back that horses once again thrived in North America. Thus, we can thank the Spanish for bringing back a quintessentially American product.

Mystery Monday, Happy Holidays

This will be the last mystery fossil for the year. After this, I, like hopefully everyone else, will be enjoying the holidays. Arkansas does not have any fossils that are terribly well associated with any of the late December holidays, but I got as close to one as I could. It is closely related to animals living here today, but it died out long before its modern relative was reintroduced. Put your guesses in the comments section and check back Friday for the answer.

It’s a Bird! It’s a Fossil Friday

Were you able to figure out what this ancient skull belonged to?

It looks for all the world like a bird, but birds don’t have teeth, do they?

Certainly not now, but early in avian history, they did. Teeth are but one of the many pieces of evidence that connects them to theropod dinosaurs like Velociraptor and Deinonychus. This particular bird was named Hesperornis regalis, the “royal western bird”. It lived in the Late Cretaceous, at the same time as such famous dinosaurs as Tyrannosaurus rex and Triceratops and marine reptiles like mosasaurs and elasmosaurs.

Grebes and loons. Studer’s Popular Ornithology: The Birds of North America. Jacob H. Studer, with illustrations by Theodore Jasper (1878)

The picture of the skull above was published by Othniel Marsh in 1880. The skeleton Marsh described and several other specimens show that Hesperornis was a diving bird, much like grebes, loons, and some rails and cormorants. Like the flightless cormorant, Hesperornis had very small wings and lacked the ability to fly. Some diving birds, like penguins, use their wings to “fly” through the water, but Hesperornis, like its modern counterparts, used their feet to propel themselves. Its feet were likely lobed, like grebes, rather than fully webbed like most aquatic birds.

Hesperornis showing jaw feathers. http://oceansofkansas.com/hesperornis.html

Hesperornis was a large bird, standing close to a meter (3 feet) tall and 1.8 meters (6 feet) in length. Its beak was long and pointed, with teeth on its maxilla and all but the tip of the mandible, or lower jaw. According to work by Tobin Hieronymus, the parts of the jaws with teeth were covered in feathers, with keratin covering the toothless portions. It lived in coastal waters, diving for fish and trying to avoid the aquatic reptiles that were the apex predators of the time.

In Arkansas, Hesperornis has been reported from the Ozan Formation in Hempstead County, a series of mostly sandy, limey mudstone, typical of warm coastal marine areas. As one would expect, given Hesperornis‘s aquatic nature, all the other fossils found with it represent marine animals, including sharks, bony fish, turtles, mosasaurs, and pliosaurs. During the Late Cretaceous, when these sediments were deposited, southwest Arkansas was at the eastern edge of the Western Interior Seaway, a marine environment created by high sea levels that flooded much of the central United States.

This find represents the southernmost extent of Hesperornis’s range, which extended up into the Arctic. It was a lot warmer then, but still cold at the poles. It should be kept in mind though, that the find consists of one partial bone, the left tarsometatarsus, part of the lower leg. It is easily recognizable as avian and has been identified as Hesperornis due to its age and size, although Dr. Larry Martin stated it could be a new taxon. We will just have to wait until more fossls turn up to know for sure. Parts of the Ozan Formation are quite fossiliferous, so there is a chance that more will be found.

The After Thanksgiving Mystery Monday

I hope you had a Happy thanksgiving, filled with all the food and family you could stand. Get back into the swing of things (before you take another break for Christmas) with another Mystery Monday fossil. Here’s a hint to get you going: while it may pose a passing resemblance to a modern animal, this one hasn’t lived since dinosaurs were walking around Arkansas. Come back Friday for the answer.