Home » Paleontology (Page 8)

Category Archives: Paleontology

Mystery Monday Returns

Welcome back! the new school year has started for most, if not all, people by now. Everyone is busily trying to figure out new schedules, new curricula, new people, sometimes even new schools. Changes are everywhere this time of year. Paleoaerie is no exception. We didn’t get quite as much done over the summer as we would have liked (does anyone?), but it was an interesting summer, filled with good and bad. To start with the bad, the UALR web design course that was initially going to work on revamping the website is no more due to unexpected shakeups at the school. Nevertheless, a different course will take a look at the site and see what they can do, although they sadly won’t have as much time to deal with it.

But there was a lot of good that happened. Big news for Paleoaerie is that we are now partnered with the Arkansas STEM Coalition, a nonprofit advocacy group for STEM education within Arkansas. This is really important for us because this means Paleoaerie now operates as an official nonprofit organization. What does this mean for us and you? It means that any donation to the site is tax-deductible. It also means that many grants that we could not apply for before are now within possible reach. Fundraising should be a bit easier from now on, which means we may be able to do much more in the upcoming future. One of the things we will be doing in the near future is a Kickstarter campaign to buy a 3D laser scanner so that we can start adding 3D images of Arkansas fossils onto the website, which will be available for anyone to use. One might ask why not use some of the cheap or even free photographic methods that are available. In a word: resolution. I’ve tried other methods. When one is attempting to make a 3D image of an intricate object only a few centimeters across, they don’t work well. If you want details to show up, you need a better system. Stay tuned for that.

But there was a lot of good that happened. Big news for Paleoaerie is that we are now partnered with the Arkansas STEM Coalition, a nonprofit advocacy group for STEM education within Arkansas. This is really important for us because this means Paleoaerie now operates as an official nonprofit organization. What does this mean for us and you? It means that any donation to the site is tax-deductible. It also means that many grants that we could not apply for before are now within possible reach. Fundraising should be a bit easier from now on, which means we may be able to do much more in the upcoming future. One of the things we will be doing in the near future is a Kickstarter campaign to buy a 3D laser scanner so that we can start adding 3D images of Arkansas fossils onto the website, which will be available for anyone to use. One might ask why not use some of the cheap or even free photographic methods that are available. In a word: resolution. I’ve tried other methods. When one is attempting to make a 3D image of an intricate object only a few centimeters across, they don’t work well. If you want details to show up, you need a better system. Stay tuned for that.

Paleoaerie is also partnering with the Museum of Discovery and the University of Arkansas at Little Rock for a National Fossil Day event on October 11. Make sure to mark your calendars and come out to the museum to see the spectacle and diversity that can be found in Arkansas. There is much more than you think. We are also working with the museum on a new dinosaur traveling exhibit. It is very cool, so watch for it later this fall.

Paleoaerie is also partnering with the Museum of Discovery and the University of Arkansas at Little Rock for a National Fossil Day event on October 11. Make sure to mark your calendars and come out to the museum to see the spectacle and diversity that can be found in Arkansas. There is much more than you think. We are also working with the museum on a new dinosaur traveling exhibit. It is very cool, so watch for it later this fall.

The last big news that happened recently is today’s Mystery Monday fossil. Someone brought me a fossil to examine a couple of weeks ago. The first amazing part of it is that is was actually a fossil. the vast majority of what people show me are just interestingly shaped rocks. This was a bona fide fossil. Not only was it a fossil, but a really cool one. The image below is a vertebra from a little seen animal in Arkansas and not at all for a very long time. The fossil is roughly 100 million years old, putting it in the Cretaceous Period. At that time, Arkansas was on the shoreline of the late Cretaceous Interior Seaway. Take a look at the image below and see if you can figure out what it came from. I’ll let you know what it is Friday. Thanks to Matt Smith for bringing this wonderful fossil to my attention. Come out to the National Fossil Day event and see it for yourself.

Taphonomy Tuesday

Taphonomy Tuesday? What the heck is taphonomy, you ask? Taphonomy is the study of burial processes and all the changes that take place betwixt death and being collected as a fossil. One might also include the effect of sexiness in what fossils get studied and forgotten about, way more people are interested in tyrannosaurs than fossil mosquitos, for instance. Change comes to all things and paleoaerie is no exception. You may have noticed that the answer to Monday’s mystery fossil did not get posted on the blog last week, although it was posted on the Facebook page. That will be rectified today. But first, a couple of pieces of news.

Taphonomy Tuesday? What the heck is taphonomy, you ask? Taphonomy is the study of burial processes and all the changes that take place betwixt death and being collected as a fossil. One might also include the effect of sexiness in what fossils get studied and forgotten about, way more people are interested in tyrannosaurs than fossil mosquitos, for instance. Change comes to all things and paleoaerie is no exception. You may have noticed that the answer to Monday’s mystery fossil did not get posted on the blog last week, although it was posted on the Facebook page. That will be rectified today. But first, a couple of pieces of news.

Mystery Monday and Fossil Friday will be suspended for the summer so I can work on other aspects of the website. I would like to make some different posts and add more to the site. however, for those of you who are primarily interested in the fossils, they will return along with school, teachers, and homework, although hopefully a bit more fun than either doing or, even worse, grading homework (trust me, having been both a student and teacher, grading is almost always more painful than doing the assignments). In the meantime, you can look forward to more varied posts, the addition of a couple of things, such as a techno page for recommended apps and multimedia and an Amazon store in which you can peruse recommended items (and in a small way support the work of paleoaerie, which while free to you, is not to me). So I hope you will stick with me through these Darwinian changes and avoid the pitchforks and torches (ed. note: in keeping with the medieval theme of the picture, I thought about saying burning faggots, but so few people these days know that in olden times, faggot simply meant a bundle of sticks, language too evolves).

The other big news is that I have started a collaboration with the Museum of Discovery in Little Rock to host a celebration of National Fossil Day in October. I am really looking forward to it and, between me and the museum educators at the MoD, we have a lot of ideas for things to do. I hope everyone can come out and enjoy the festivities and learn about fossils in Arkansas and beyond firsthand.

The other big news is that I have started a collaboration with the Museum of Discovery in Little Rock to host a celebration of National Fossil Day in October. I am really looking forward to it and, between me and the museum educators at the MoD, we have a lot of ideas for things to do. I hope everyone can come out and enjoy the festivities and learn about fossils in Arkansas and beyond firsthand.

Now, for that fossil…Did any of you recognize this as the skull of a mosaaur, specifically that of Platecarpus? To picture a mosasaur, imagine a komodo dragon, replace the feet with flippers, and compress the tail so it is taller than it is wide (aka laterally compressed) so it looks more fish-like than lizard-like, and you have a pretty good view of a mosasaur. There is a reason for that. Komodo dragons are part of a group of lizard called monitor lizards, which are thought to be close relatives of mosasaurs and so are likely an excellent model for what the ancestral animal of mosasaurs looked like before they became aquatic.

Platecarpus was a carnivorous marine reptile that swam in the Cretaceous seas. While dinosaurs like Tyrannosaurus rex and Triceratops roamed the land, Platecarpus and its relatives patrolled the oceans. This is one of the most common mosasaurs, so much of what we know about them comes from fossil of this genus. It was smaller than many of the other mosasaurs. Some, like Kronosaurus, could reach up to 17 meters, but Platecarpus only averaged around 4-7 meters. Its name means “flat wrist,” alluding to the flippers, although it hardly distinguishes them from other mosasaurs in this regard. What did make them stand out from the other mosasaurs was a relatively shorter snout with eyes that faced more forward, so it probably had better stereoscopic vision, that is, it had better depth perception than most others of its kind. This may be why it had a shorter snout, to prevent the snout from blocking its field of view. Like other mosasaurs, Platecarpus had two rows of teeth on its palatine bones, forming the roof of its mouth. This arrangement actually isn’t all that unusual in lizards and snakes, it is really common in fish. The teeth (all of them, not just the palatal teeth) were pointed and conical, although not as sharp as some of its kin, indicating it went after small, soft prey, like small fish and soft invertebrates like squid or perhaps even jellyfish. They could have gone after larger prey like crocodilians do, but unlike crocodilians which have a strong skull capable of withstanding the forces of ripping a prey item apart, Platecarpus had a much weaker skull which would likely not have stood up to the stresses of the crocodilian death roll (this is when they grab a limb and spin until the limb is ripped off, the moral of the story is of course, never dance with a gator). The overall shape of Platecarpus is stockier than most mosasaurs. This would have had the effect of decreasing surface area relative to body weight, which could have increased its metabolism by holding in heat better.

KUVP1001. Mike Everhart. http://www.oceansofkansas.com

One of the things that makes Platecarpus as a genus so interesting is the fossils that have been found with soft tissue preservation. In one, along with parts of the skin, parts of the trachea (windpipe) were preserved. Originally, they were interpreted as part of a dorsal fin, thus all the early pictures of mosasaurs with fins along their backs. However, it was quickly discovered what the traces really were. To his credit, Williston, the scientist who had reported in 1899 the traces as a dorsal fins was the one who published another short paper three years later saying he had made a mistake and the fossil really showed the cartilaginous rings found in trachea. The tracheal rings have also been interpreted as showing the branching point between the two lungs, which is important because it answered a question about their origins. Every researcher agrees that mosasaurs are lepidosaurs, the group including lizards and snakes, but what wasn’t known was whether or not mosasaurs were derived from aquatic lizards or from snakes. The discovery of a trachea showing two lungs confirms the origin within lizards (snakes only have one lung). It may still be that snakes evolved from mosasaurs, but that is not very likely.

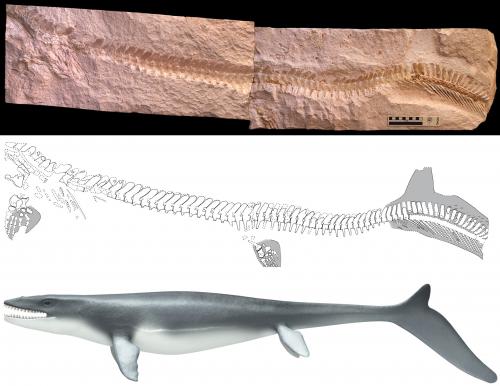

The other piece of soft tissue that has been found is the outline of the tail showing a lobe on the tail forming a very shark-like tail. Until this time, many people had thought the mosasaur swam with an eel-like motion, but the tail and the deep caudal fins indicate a much faster shark-like swimming motion. This in turn has caused people to reevaluate the view they were slow ambush predators, supporting a more active predatory forager. Whether or not other mosasaurs had this fin is currently unclear, so there may have been specializations within this group not seen in the larger mosasaur family. Another such example is the discovery of what has been interpreted as thicker eardrums, which may have allowed them to dive to deeper depths.

Tail fluke preserved around skeleton. Credit: (top) Photograph (by Johan Lindgren), (centre) sketch indicating the bones and skin structures preserved (by Johan Lindgren), and (bottom) life reconstruction (by Stefan Sølberg) of Prognathodon sp.

The southwestern corner of Arkansas was at the edge of the Late Cretaceous Western Interior Seaway, so we have several fossils of them in places like Clark, Hempstead and Howard counties, although you can find them all over the world in the right type of rocks. You can find them in the Brownstone and Marlbrook Marl Formations. These formations are indicative of warm, shallow seas, much like the Bahamas today, which considering the locations, shouldn’t come as too much of a surprise to people. If you were taking a nice vacation on the warm Cretaceous beaches 80-85 million years ago, you might have tried fleeing into the water to avoid the dinosaurs on the beach, but you would have been no safer in the water.

I would like to thank Rachel Moore, who supplied a lot of the research involved in putting this post together.

The ethics of fossil collecting

Today’s Google doodle celebrates the 215th birthday of Mary Anning. She was one of the first people to help usher in the modern age of paleontology as a science and was the prime worker on the Jurassic Coast near Dorset, England, probably the most important fossil site for marine reptiles in the world. The Natural History Museum of London calls her “the greatest fossil hunter ever known..” Among other finds, she is credited for finding the first correctly identified skeleton of an ichthyosaur, the first complete specimens of a plesiosaur, the first pterosaur outside Germany, and identifying coprolites as fossil feces. Until that time, they were called bezoar stones, indigestible masses found within the digestive system. They were rumored to be an almost universal antidote for poisons and were used as such in J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series. The first woman to receive a eulogy at the London Geological Society, an honor given only to distinguished member scientists (she wasn’t even a member because the society did not accept women at the time, they just took her work and published it under their names), Mary Anning was widely sought after by researchers in her time for her expertise.

This brings up an interesting debate. It is hotly debated what role commercial fossil dealers have in paleontology. The current majority consensus as presented by the Society for Vertebrate Paleontology is that they should be stopped because all the fossils they collect are sold, almost always, to private collectors, thereby removing them from scientific study. Fossils that are not in the public trust (like a museum) are not accessible to other scientists to study, so all the knowledge that may be gleamed from their study is lost to the public. They explicitly state this in their bylaws. Section 6, Article 12 states: “The barter, sale or purchase of scientifically significant vertebrate fossils is not condoned, unless it brings them into, or keeps them within, a public trust. Any other trade or commerce in scientifically significant vertebrate fossils is inconsistent with the foregoing, in that it deprives both the public and professionals of important specimens, which are part of our natural heritage.”

They have a point. Few fossils collected by commercial fossil dealers ever get scientifically studied. Who knows how many priceless and important fossils are locked away in someone’s private collection. Museums do not have the resources to compete with private competitors to buy fossils except in the rarest of occasions and even then, it depends on the finances and good will of private individuals willing to donate to the museum for that purpose. The tyrannosaur named Sue sold at auction for $7.6 million to the Field Museum in Chicago, who needed the help of the California State University system, Walt Disney Parks and Resorts, and McDonald’s, along with numerous individual donors to raise the money. Researchers collecting fossils must always be on their guard to protect their dig sites due to the common occurrence of thieves stealing fossils from their dig sites to sell them. Many paleontologists have stories of finding a skeleton at the end of the season and having no time to collect it, only to come back the next season to find someone has collected the sellable parts and not uncommonly have smashed the rest. Even if the fossils find their way to a public institution where they can be studied, most commercial fossil collectors do not take sufficient notes about location and all the details at the site to make the find reliable enough to study well. It is often said that a fossil without provenance data has little more worth than having no fossil at all and for good reason. If you don’t know where a fossil came from, there is little you can say about it and it is impossible to place it in context with other fossils.

On the other hand, commercial fossil collectors say that without them, most of the fossils they collect would have eroded away and been gone completely with no record of them ever having existed at all. There simply aren’t enough paleontologists and money in academia to collect all the fossils they do and they are right. The tyrannosaur Sue is a great example of a dinosaur fossil that may not ever have been found if it were not for commercial fossil dealers. What makes this point important for this essay is that Mary Anning was a commercial fossil dealer. She funded her research and supported herself by selling fossils. Without the income she received from fossil sales, she would never have been able to make the discoveries she did.

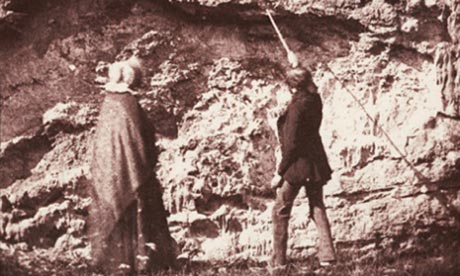

Possibly the only known photograph of Mary Anning and she is not even credited in the photo, which is called The Geologists. 1843, Devon. Salt print by William Henry Fox Talbot. Photograph: The National Media Museum, Bradford

So who is right? Maybe they both are. It is undeniable that unscrupulous poachers and fossil dealers steal and destroy priceless fossils which never enter the public and academic consciousness, but it is also undeniable that commercial fossil dealers have contributed greatly to our knowledge of paleontology. The AAPS, Association of Applied Paleontological Sciences, an organization representing commercial fossil dealers, advocates for responsible collecting, having a professional academic work with commercial fossil dealers so any finds can be studied. Their position would indeed help bridge the gap between the academic and the commercial dealer. However, this requires the benevolence of the collectors and many, possibly most, are uninterested in letting academics study their fossils. While the fossils may be able to be studied during the time they are found and prepared (removing the encasing rock and putting the pieces together), most of the study comes after this point. A fossil in private hands can easily become lost and access is at the mercy of the owner. A museum, on the other hand, is required to maintain records of the fossils and provide access to anyone who wants to study them.

So what is to be done? Currently, it is illegal to collect vertebrate fossils on Federal land. The reasoning is that Federal land is owned by everyone. As such, anything on Federal land must be protected for all citizens, making collections for private sale not in the interests of the country as they take fossils out of the public trust and therefore inaccessible to the public. States have their own rules, some make it illegal, others have no specific laws concerning fossil collections. On private land, there are no restrictions. Any fossils found on private property are the property of the land owner and they can do whatever they want.

So what is to be done? Currently, it is illegal to collect vertebrate fossils on Federal land. The reasoning is that Federal land is owned by everyone. As such, anything on Federal land must be protected for all citizens, making collections for private sale not in the interests of the country as they take fossils out of the public trust and therefore inaccessible to the public. States have their own rules, some make it illegal, others have no specific laws concerning fossil collections. On private land, there are no restrictions. Any fossils found on private property are the property of the land owner and they can do whatever they want.

What is the correct answer? That depends on your point of view. Certainly the collective point of view has changed through time. What do you think?

Mystery Monday

For today’s Mystery Monday fossil, see if you can identify this creature.

Fossil Friday

It’s Friday, time for the answer to Monday’s mystery fossil. Were you able to identify it?

These fossils are from a fish called Enchodus, the “saber-fanged herring.” Teeth of Enchodus are commonly found in the Cretaceous-aged rocks in southwestern Arkansas, especially near Malvern and Arkadelphia in the Arkadelphia and Marlbrook Marl Formations, up into the Paleocene rocks of the Midway Group a bit farther north. In other places you can even find them in rocks of Eocene age, although you will have much better luck in the Cretaceous rocks. At this time, southern Arkansas was shallow to coastal marine. Go to the Bahamas, imagine Enchodus, mosasaurs, plesiosaurs, and plenty of sharks in the water around the islands and you would have a good picture of the landscape back then. They were abundant at the end of the Mesozoic Era and survived the asteroid impact that rang the death knell for many animals, including the non-avian dinosaurs. But they never regained their prominence as a key member of the marine ecosystem, eventually dying out completely in the Eocene sometime around 40 million years ago (the Eocene lasted from 55 to 34 million years ago).

These fossils are from a fish called Enchodus, the “saber-fanged herring.” Teeth of Enchodus are commonly found in the Cretaceous-aged rocks in southwestern Arkansas, especially near Malvern and Arkadelphia in the Arkadelphia and Marlbrook Marl Formations, up into the Paleocene rocks of the Midway Group a bit farther north. In other places you can even find them in rocks of Eocene age, although you will have much better luck in the Cretaceous rocks. At this time, southern Arkansas was shallow to coastal marine. Go to the Bahamas, imagine Enchodus, mosasaurs, plesiosaurs, and plenty of sharks in the water around the islands and you would have a good picture of the landscape back then. They were abundant at the end of the Mesozoic Era and survived the asteroid impact that rang the death knell for many animals, including the non-avian dinosaurs. But they never regained their prominence as a key member of the marine ecosystem, eventually dying out completely in the Eocene sometime around 40 million years ago (the Eocene lasted from 55 to 34 million years ago).

The fish reached sizes over 1.5 meters, which makes them on the large side, but not really big, considering there were mosasaurs in the same waters that surpassed 10 meters. Still, with fangs longer than 5 cm, they would not have been fun to tangle with. They were clearly effective predators on smaller fish and possibly soft animals like squid. At the same time, fossils have been found showing they were themselves prey for larger predators, such as sharks, the above-mentioned mosasaurs, plesiosaurs, and even flightless seabirds such as Baptornis. Baptornis was a toothed, predatory bird, but as it only reached 1 meter or so, it would have only been able to hunt young Enchodus. So like many of us today, Baptornis was always up for a good fish fry.

Hesperornis, a larger version of Baptornis, and a few Enchodus feeding on some herring-type fish. Picture by Craig Dylke.

Enchodus is often called the “saber-fanged herring,” although it is unrelated to herrings. So what then was it? Herrings are what is known as forage fish, meaning they are mostly prey items of larger fish and other animals. Most of the fish called herrings are in the family Clupeidae in the groups Clupeiformes, which includes such well-known fish as sardines and anchovies. Enchodus, on the other hand, has been placed into the group Salmoniformes, which includes trout, char, and of course, salmon. When one typically thinks of trout and salmon, one doesn’t think of bait fish, they think of the fish that eat the bait fish. Thus, Enchodus would better better described as a fanged salmon (they were a bit large to call them fanged trout).

Mystery Monday

Time for another Mystery Monday. Teeth like this are reasonably common in Arkansas rocks of a particular age. See if you can tell what it is.

Puma concolor, The Ghost Cat of Arkansas

I have a special treat today. I am pleased to announce our first guest post on paleoaerie. John Svendsen found a set of puma fossils when he was in high school. Today, he shares with us what he has learned about them since that time.

“Masters of stealth, they seldom step from the shadows.”

For many years people have reported sightings of mountain lions and pumas in Arkansas yet the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission has repeatedly disputed such claims. Rather the AGFC believes that any such sightings are simply of feral mountain lions released from captivity that should be shot on sight. Why would the AFGC deny the obvious – that living, breeding mountain lions can be found in the state? As noted by Bryan Hendricks (2009), if the AGFC acknowledges the presence of a sustainable population of wild mountain lions in Arkansas, then it will be compelled to draft a management plan to assure their survival. That means the agency will have to devote money and manpower to compile a population estimate, and then hold meetings to get public input for management options. By virtue of the mountain lions endangered status, a management plan would likely seek to increase or maintain its population – obviously, deer and turkey hunters and livestock farmers would feel at risk having this predator protected by law and would seek litigation or legislation to assure that they can continue to kill mountain lions on sight.

Fortunately there was a time tens of thousands of years ago when mountain lions roamed the state without fear of man. This ancient pre-historic cat roamed the hills and savanna of North America for millions of years in the company of dire wolves, saber-tooth tigers, giant sloths, peccaries and cave bears. Just as these mammals became extinct so did the mountain lion and by the late Pleistocene (approximately 10-12,000 years ago) no mountain lions survived in North America. Fortunately a few mountain lions from South America migrated northward and reestablished living populations throughout much of North America. The mountain lions we see today in Arkansas are the ancestors of this small migrating band from South America.

The mountain lion, known scientifically as Puma concolor, occupies a vast range of ecological zones as diverse as desert, tropical rain forest and alpine steppes (Kurten, 1976). Cats such as P. concolor are poorly represented in the fossil record and taxonomic research on felids is somewhat incomplete. Much of what is known about their evolutionary history is based on mitochondrial DNA analysis and still there are substantial confidence intervals in suggested dates and lots of room for error (Culver et. al, 2000). We do know however that pumas come from a very long line of evolution with episodic bursts of development and diversification that can be traced 40 to 60 million years ago through the late Tertiary period.

These prehistoric creatures are large cats with powerful bodies. Males can weigh 250lbs. (103 kg) with a length of 4.5 feet and a 3 foot tail. It is the second largest cat in the Americas, after the Jaguar, and it is the fourth heaviest cat in the world, after the Tiger, Lion, and Jaguar. It is a solitary cat and rarely is seen in the presence of other cats except during breeding and the raising of a litter. It is an apex predator and is specialized for the task: binocular vision, acute sense of smell and sight, retractable claws, strong canine teeth and masseters, and powerful forearms and legs allowing it to leap 40 feet, jump 15 feet high and pounce from a height of 5-story building. Few animals are capable of outrunning, alluding or surviving a puma attack — fortunately they prey chiefly on the weak and injured and thus strengthen the gene pool of those on which they prey.

Puma fossils are rare in the fossil record of Arkansas and have only been identified from: Conard Fissure and Svendsen Cave (see Figure 1). Conard Fissure is a geologic feature in Northern Arkansas where a deposit of Pleistocene fossils were discovered in 1903 when Waldo Conard was searching through fissures and crevices on his land in search of lead. In one of these fissures he found a “bone mine” with thousands of bones preserved in limestone – thirty-seven genera and fifty one species, of which nearly half are extinct. The original excavation of the fissure was performed by Barnum Brown, the initial discoverer of Tyranosaurus rex, and yielded an assortment of small animals and rodents but also larger mammals including peccary, deer, bear, wolves and foxes. This entombment of a wonderful assemblage of mammal is accounted for by the fact that the fissure long remained open and was inhabited in the late Irvingtonian (240,000-300,000 years BP) by many carnivorous animals.

Puma fossils are rare in the fossil record of Arkansas and have only been identified from: Conard Fissure and Svendsen Cave (see Figure 1). Conard Fissure is a geologic feature in Northern Arkansas where a deposit of Pleistocene fossils were discovered in 1903 when Waldo Conard was searching through fissures and crevices on his land in search of lead. In one of these fissures he found a “bone mine” with thousands of bones preserved in limestone – thirty-seven genera and fifty one species, of which nearly half are extinct. The original excavation of the fissure was performed by Barnum Brown, the initial discoverer of Tyranosaurus rex, and yielded an assortment of small animals and rodents but also larger mammals including peccary, deer, bear, wolves and foxes. This entombment of a wonderful assemblage of mammal is accounted for by the fact that the fissure long remained open and was inhabited in the late Irvingtonian (240,000-300,000 years BP) by many carnivorous animals.

Svendsen Cave yielded the remains of a puma following its discovery in 1974 by two young spelunkers, John Svendsen and Ola Eriksson who were still in high school at the time (Pluckette, 1975). The cave is developed in dolomitic limestone of the Everton Formation and contains over a mile of mapped passage and three stream systems. The skeletal remains were encased in a travertine ledge only 500 feet from the entrance of the cave (see Figure 3) but passage to the remains included a low strenuous crawl and squeeze, a siphon and two climbs. The puma is presumed to have entered the cave from an entrance now unknown and may have been washed to the depositional site.

Svendsen Cave yielded the remains of a puma following its discovery in 1974 by two young spelunkers, John Svendsen and Ola Eriksson who were still in high school at the time (Pluckette, 1975). The cave is developed in dolomitic limestone of the Everton Formation and contains over a mile of mapped passage and three stream systems. The skeletal remains were encased in a travertine ledge only 500 feet from the entrance of the cave (see Figure 3) but passage to the remains included a low strenuous crawl and squeeze, a siphon and two climbs. The puma is presumed to have entered the cave from an entrance now unknown and may have been washed to the depositional site.

Svendsen Cave proved to be a marvelous find as the remains were chiefly intact and materials that were recovered included: partial skull with teeth, partial left mandible with teeth, left humerus, scapula, ribs, and vertebrae (see Figures 4-6). No exact date can be assigned to the Svendsen puma albeit antiquity is evident given mode of occurrence and lack of metastable materials in the skeletal remains. At the depositional site, the bone-bearing travertine is undergoing dissolution and the sediments are being removed by a nearby stream. Thus a climatic regimen of less than the present level of precipitation which allowed formation of the travertine ledge is indicated for the cave area during deposition of the puma (Pluckette, 1975). Given the dimensions of the dentition, mandible and humerus obtained from the site a dating of the Middle Pleistocene, Ionian stage (781 to 126 thousand years ago), is presumed albeit the fossils could be much older.

Svendsen Cave proved to be a marvelous find as the remains were chiefly intact and materials that were recovered included: partial skull with teeth, partial left mandible with teeth, left humerus, scapula, ribs, and vertebrae (see Figures 4-6). No exact date can be assigned to the Svendsen puma albeit antiquity is evident given mode of occurrence and lack of metastable materials in the skeletal remains. At the depositional site, the bone-bearing travertine is undergoing dissolution and the sediments are being removed by a nearby stream. Thus a climatic regimen of less than the present level of precipitation which allowed formation of the travertine ledge is indicated for the cave area during deposition of the puma (Pluckette, 1975). Given the dimensions of the dentition, mandible and humerus obtained from the site a dating of the Middle Pleistocene, Ionian stage (781 to 126 thousand years ago), is presumed albeit the fossils could be much older.

No other sites in Arkansas have been discovered which have yielded prehistoric fossils of the P. concolor albeit more are likely waiting to be found in the future.

No other sites in Arkansas have been discovered which have yielded prehistoric fossils of the P. concolor albeit more are likely waiting to be found in the future.

Conclusion

P. concolor is still a resident of Arkansas. In most of North America P. concolor is currently classified as an endangered species and protected, whereas in Arkansas it is currently legal to shoot and kill P. concolor upon sight as the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission has declared, “All cougars (mountain lions) in Arkansas are considered to be escaped pets or the feral progeny of escaped pets and hence it is legal to kill such animals.” The future of this magnificent big cat lies at the mercy of people who must preserve its natural environment and allow it free passage.

References

Brown, B. 1908. The Conrad Fissure, a Pleistocene bone deposit in northern Arkansas; with descriptions of two new genera and twenty new species of mammals. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. Mem. 9: 155-208.

Culver M1, Johnson WE, Pecon-Slattery J, O’Brien SJ. 2000. Genomic ancestry of the American puma (Puma concolor). Journ. of Heredity. 91: 186-197.

Hendricks, B. 2009. “Arkansas sportsman: AGFC not lying just avoiding furball over big cats.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. Feb. 8, 2009.

IUCN, 2010. “The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species” (On-line). Mammals. Accessed March 29, 2011 at http://www.iucnredlist.org/initiatives/mammals.

Johnson, W.E., Eizirik, E., Pecon-Slattery, J., Murphy, W.J., Antunes, A., Teeling, E. and O’Brien, S. J. 2006. The Late Miocene radiation of modern Felidae: A genetic assessment. Science 311:73-77

Kurten, B. 1965. The Pleistocene felidae of Florida. Bull. Florida State Mus. 9(6): 215-273.

Kurten, B. 1976. Fossil Puma (Mammalia: Felidae) in North America. Netherlands Journ. of Zoo. 2694): 502-534.

O’Brian, S. J., and Johnson, W. E. 2005. Big Cat Genomics. Ann. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 6: 409-29

Pluckette, W. L. 1975. An occurrence of the Puma, Felis concolor, from Svendsen Cave, Marion County, Arkansas. Ark. Acad. Of Sciences, Vol. 29, p. 52-53.

Turner, A. 1997. The Big Cats and Their Fossil Relatives: an Illustrated Guide to Their Evolution and Natural History. New York: Columbia University Press.

Young, S.P. and Goldman, E.A. 1946. The puma, mysterious American cat. Am. Wildlife Inst. 358 p.

The answer to last week’s Mystery Monday

The answer to last week’s Mystery Monday fossil was supposed to be posted last Friday, which didn’t get done. I am going to have to make some changes in the schedule or change the way I do things because I simply don’t have the time to post a new fossil and give a full discussion of it every week and do anything else. So if you have any suggestions on how you think changes would be best done, let me know. I could cut back to every two weeks; still give a fossil every week, but not go into much discussion of what it is each week; or some other possibility. Let me know your preferences.

At any rate, for the last Mystery Monday fossil, I posted this little fossil.

What we have here is a little goniatite ammonoid that has been pyritized, meaning that the shell has been replaced with pyrite. This type of fossilization is pretty common. As the bacteria eat the organism, some of them will release sulfur, which then combines with the hydrogen in the water to form hydrogen sulfide. When it precipitates out of the water, it usually does so as pyrite. In some cases, like in this one, the pyrite crystals can replace the organism so well that it makes a detailed copy of the original. For obvious reasons, this type of fossilization is called replacement, in which the original oranism is replaced with a mineral, be it calcium carbonate, iron, opal, quartz, or in this case, pyrite.

So what are goniatite ammonoids? Ammonoids are part of the group (often called phylum, but for various reasons the specific rank of the group is often no longer used) Mollusca; which includes snails, (gastropods), clams (Bivalvia, meaning two shells, or less commonly, Pelecypoda, meaning hatchet foot), and the Cephalopods.

Cephalopods include the squids and octopuses, as well as the Nautilus, which is what concerns us here. If you aren’t familiar with a nautilus, think of a squid inside a spiral shell. Squids used to have shells, either long, straight ones or curved and coiled ones. The only one left of these shelled squid is the nautilus. However, you can still see the remnant of the shell in an internal structure called a squid pen, or in the case of cuttlefish, the cuttlebone. In either case, they are the last vestiges of the external shells we see in the nautilus and the ammonoids.

During the Paleozoic and Mesozoic Eras, ammonoids were much more common and much more diverse. During the Jurassic and Cretaceous Periods during the Mesozoic, the type of ammonoids that were most common were the more familiar fossils known as ammonites. Goniatites were much earlier and lived during the Paleozoic.

How does one tell the difference between the different types of ammonoids? Look at the internal partitions. These partitions, called septae, separate the chambers within the shell. As the animal grows, it adds material to the edge of the shell, making it larger and larger at that end. Once the shell gets big enough, the animal will create a new partition in the back, separating the current body chamber from the earlier, smaller one. A small hole is left in the septae so the siphuncle, a thin tube, can pass through, connecting all the previous chambers. The siphuncle could then be used to pump water or gas in and out of the chambers so they could be used as ballast, allowing fine control of their buoyancy.

The septae in the nautiloids (the group of ammonoids containing the modern nautilus) are all very smooth, forming a nice curve. The nautiloid septae curve inwards, whereas the ammonoids curve outwards to some extent. Ammonoid septae are also much more complex. Goniatites, the earlier forms, had simple wavy septae. Ceratitic ammonoids created septae in which the waves were more jagged, with what often looks like little saw-toothed crenulations. The later ammonites (many people call all of them ammonites, but this term more properly only refers to the more derived subset) had very complex septae, showing several smaller wave patterns overlaid upon the larger wave.

The septae in the nautiloids (the group of ammonoids containing the modern nautilus) are all very smooth, forming a nice curve. The nautiloid septae curve inwards, whereas the ammonoids curve outwards to some extent. Ammonoid septae are also much more complex. Goniatites, the earlier forms, had simple wavy septae. Ceratitic ammonoids created septae in which the waves were more jagged, with what often looks like little saw-toothed crenulations. The later ammonites (many people call all of them ammonites, but this term more properly only refers to the more derived subset) had very complex septae, showing several smaller wave patterns overlaid upon the larger wave.

Ammonoids were very common in the Paleozoic and Mesozoic and were found throughout the oceans of the time. They typically lived in shallow marine environments all over the world. They also evolved rapidly, so new species tended to appear and disappear on a fairly regular basis. This abundance, diversity, and rapid turnover make them prime index fossils. Index fossils are those fossils which are useful for dating the rock layer and correlating the layer from one spot to another. Using index fossils allows us to piece together a complete sequence of events even if there is no one place that has the entire sequence of rocks preserved. As a result, any fossils that can be used as index fossils become very important to people trying to figure out the history of life on earth, such as this little ammonoid. If you want to find one for yourself, look in almost any of the limestone or chert formations in the Ozark mountains. There are plenty.

Taking a Bite Out of Fossil Friday

My apologies for getting this out so late. But now that we’re here, could you tell what the mystery fossil for this week was? It was a very unusual creature.

The creature in the picture is a representative of an early shark called Falcatus. It was a very strange shark, in which the males had a forward-pointing spike on its head. This is one of the earliest examples of sexual dimorphism in the fossil record. Sexual dimorphism is when the male and females look different. Humans are sexually dimorphic in a variety of ways, but the classic example is the peacock with its extravagant tail. They are so dimorphic that many people do not even realize the term peacock only applies to the male of the peafowl species. The females are called peahens.

Falcatus was chosen this week because of an interesting shark fossil found in 325 million year old limestone near Leslie, AR. The fossil was recently published and got a lot of press. Pictures of the fossil itself show what appears to be little more than a couple of lumpy concretions stuck together. There is little there that resembles anything like a shark. At least, until you look inside. A concretion is an inorganic structure consisting of layers of minerals that have been precipitated around a central core, much like a rocky onion. Oftentimes, a fossil lies at that core and served as the basis upon which the mineral precipitation got started. So one never knows what one will find cracking open a concretion. It may be nothing more than concentric mineral bands, or it may be an exquisite fossil preserved for the ages. In this case, the scientists got lucky. Not only was there an exquisite fossil, but one in which few had ever seen before: the skeletal structure of an early shark’s gill basket.

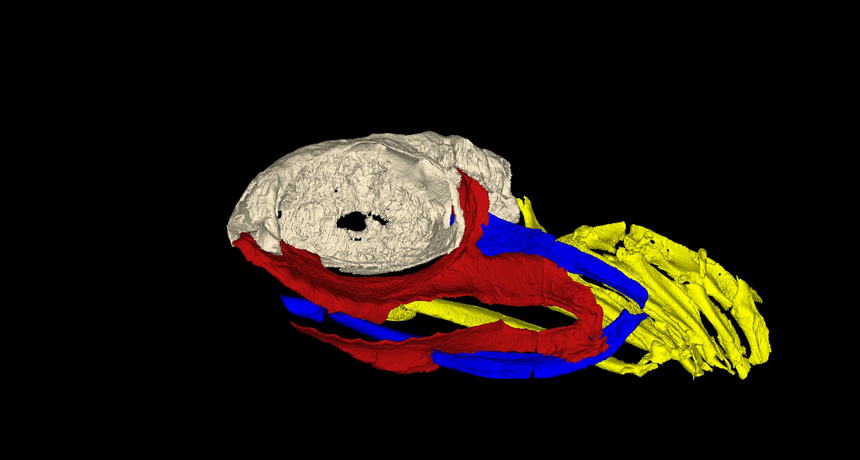

A 3D reconstruction of the skull of Ozarcus mapesae. The braincase is shown in light grey, the jaw is shown in red, the hyoid arch is shown in blue, and the gill arches are shown in yellow. ©AMNH/A. Pradel

The researchers named the fossil Ozarcus mapesae, for the Ozarks in which it was found and for Royal and Gene Mapes, geology professors at Ohio University. The Mapes are also paleontologists and have collected a large number of fossils, one of which happened to be this curious-looking concretion. Small teeth on the exterior pointed to possibly more interesting material inside, so they CT-scanned it, which revealed the remains of the head of the shark. But to get better detail, they had to use a synchotron. This technology is new and expensive enough that it was not possible to look at the fossil this way until recently (a good example of why we preserve fossils in museums, you never know when future technology will allow examination in ways never thought of before).

The gill basket goes by many names, the branchial basket, branchial arches, gill arches, etc. but they all refer to the skeletal supports for the gills. To the shark, they are important for holding up the gills and forming the path for water to flow over the gills so the shark can breathe. For us, they are important because the arches evolved into a variety of structures, primarily the jaws and hyoid, a small bone in the throat to which the back of the tongue is attached. Because of the importance of jaws, the evolution of those structures has been a big topic of interest. The traditional view has been that the first jawed fish, the placoderms, evolved into the early precursors of the sharks, which then evolved into the early bony fish, the osteichthyans. The sharks then were expected to have a more primitive structure than bony fish. This story makes sense, given that the order of appearance in the fossil record pretty much matches what we would expect and the skeletal structures look more primitive in sharks than bony fish. Of course, despite the common view that sharks are relics of a bygone age, they have had over 400 million years to evolve after they split off from bony fish. How likely is it that they would have retained such ancestral characteristics for all this time? To answer that question, we can look at the fossil record to tell us what they were like at the earliest stages.

The big problem with examining the fossil record of sharks is that sharks are chondricthyans. They do not make bone. Other than the teeth, the skeleton is supported by a simpler set of calcium phosphate crystals. Unlike bone, which has a very structured arrangement of crystals and connective tissue, the bones in sharks are made of cartilage and a haphazard set of disorganized crystals, which fall apart shortly after the animal dies. Thus, finding any fossils of sharks that contain more than the teeth is extremely rare. Finding ones in which everything is still in place is almost impossible. Fortunately, over a long enough period of time, even the almost impossible will happen eventually. That is the thing with large numbers and vast amounts of time, our perception of what is unlikely doesn’t really work. For instance, given a 1 in a million chance that a tweet on Twitter will have something requiring the security team to deal with, that still gives them 500 tweets every single day. That “almost impossible” fossil was found with Ozarcus. This fossil provided our first look at what the throat of a primitive shark actually looked like.

The big problem with examining the fossil record of sharks is that sharks are chondricthyans. They do not make bone. Other than the teeth, the skeleton is supported by a simpler set of calcium phosphate crystals. Unlike bone, which has a very structured arrangement of crystals and connective tissue, the bones in sharks are made of cartilage and a haphazard set of disorganized crystals, which fall apart shortly after the animal dies. Thus, finding any fossils of sharks that contain more than the teeth is extremely rare. Finding ones in which everything is still in place is almost impossible. Fortunately, over a long enough period of time, even the almost impossible will happen eventually. That is the thing with large numbers and vast amounts of time, our perception of what is unlikely doesn’t really work. For instance, given a 1 in a million chance that a tweet on Twitter will have something requiring the security team to deal with, that still gives them 500 tweets every single day. That “almost impossible” fossil was found with Ozarcus. This fossil provided our first look at what the throat of a primitive shark actually looked like.

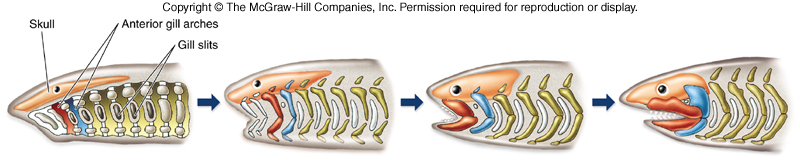

Let’s have a bit of background to cover what we have known of early jaw evolution up to this point. Placoderms, armored fish from the early Paleozoic Era, were the first animals with jaws. The jaws themselves appear to develop from the first gill arch, according to a lot of embryological studies on modern animals.

The studies haven’t really answered where the bone came from though. In placoderms, it is pretty clear the armor came from modifications of the dermis, the basal layer of the skin. But they also have internal bone forming their skeleton. Modern sharks have no bone other than teeth and bony fish have jaws made from that dermal bone. In addition to the origins of the bone, there is the matter of how the bones are attached to the skull. The upper jaw is formed by a embryological structure called the palatoquadrate (the top part of the first gill arch), so named because bones called the palatine and quadrate form from it. The bottom jaw forms from what is called Meckel’s cartilage (the bottom part of the first gill arch). In modern fish, the palatoquadrate is braced against the skull only at the front, with the back unattached. The jaw joint itself is attached to a bone called the hyomandibular, which forms from the second gill arch. The hyomandibular acts like a swinging pivot, allowing the jaw to open very wide. When the jaw joint gets pulled forward, the back of the upper jaw can move down, using the point where the front part is braced as the pivot point. Sharks take this to an extreme, not bracing the upper jaw on anything at all, with the jaws attached solely by the hyomandibular bone (the “hyostylic” joint) allowing both the upper and lower jaw to move forward when they open their mouths. So when you see that shark opening its jaws and it looks like they are coming right out at you, they really are. For a great example of a hyostylic jaw joint, check out the goblin shark.

Unfortunately, when we look at the earliest fossil sharks and bony fish, both of them show a jaw in which the upper jaw is braced against the skull in both front and back (the “amphistylic” joint). So it doesn’t tell us much about how the sharks fit into the sequence. One might say that it seems logical to think the bony fish came first, loosening the jaw in the back and then the chondrichthyans took this one step farther. But surely, others might say, the fact that bony osteichthyans have a more advanced bony skeletal structure means they would have to have come later, right? Here again, the fossil record doesn’t help here because the earliest representatives of both groups appear close enough in time that it cannot be strongly stated which came first.

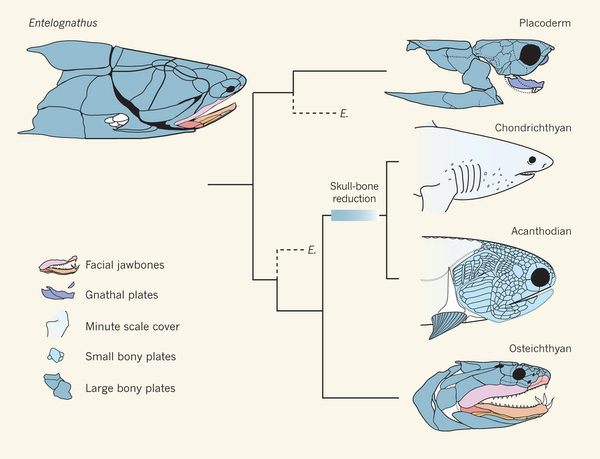

That is where things were, until 2013, when the fossil record started answering these questions. A placoderm called Entelognathus was published in 2013. This fossil was of great interest because it showed the structure of the jaws in great detail. Entelognathus had a jaw that looked very much like an osteichthyan. This fossil was 419 million years old, so it was likely too late to be ancestral to either chondrichthyans or osteichthyans, but old enough to be very close to the ancestral form. What Entelognathus tells us is that the bones forming the jaws in placoderms was already like those seen in modern bony fish, indicating that sharks would have started out with bone, but lost it during their early evolution. Of course, since sharks don’t have bone, this was hard to demonstrate on sharks, so the question was still unsettled.

What Entelognathus says about fish relationships. Palaeontology: A jaw-dropping fossil fish. Matt Friedman & Martin D. Brazeau Nature 502, 175–177 (10 October 2013) doi:10.1038/nature12690

Outside of the actual jaws themselves, there are all the other support structures around the jaw, such as the hyoid bone. Many of these structures are formed from the next few gill arches (earlier jawless fish had at least seven gill arches, so using a few to make the jaws and throat still leaves plenty for gills). The skeletal structures in bony fish that support the gill arches form a fairly simple chevron, or wide v shape, whereas the sharks have a slightly more complicated structure. But if finding fossils of shark skeletal structures is rare, finding one with tiny gill arch supports still in position is almost impossible. There is where Ozarcus comes in, because it is here that the almost impossible becomes reality. Once the researchers were able to see inside the fossil with the synchotron, they were able to see preserved gill arch supports in position. That position resembled the simple chevron shape of modern osteichthyans.

Gill arch supports in Ozarcus are similar to bony fish (right) and not the condrichythyans (left). Pradel A., Maisey J.G., Tafforeau P., Mapes R.H. and Mallatt J. (2014) A Palaeozoic shark with osteichthyan-like branchial arches. Nature DOI: 10.1038/nature13195

Thus, between Entelognathus and Ozarcus, we can confidently assess the development of jaws as having started in placoderms with primitive, osteichthyan jaws. We have evidence of the bony origins of the jaws from Entelognathus and evidence from the gill arches from Ozarcus, so we now have plenty of evidence to strongly support the claim that the chondrichthyans are not in the evolutionary pathway to modern jaws at all. They are an offshoot that actually lost bone to form a more flexible skeleton for some reason. Whether it was mechanical advantage for their lifestyle, such as increasing flexibility, or a reduction in mineral storage, who can say.

This new view of jaw evolution demonstrates that the common view of sharks as being evolutionary relics is wrong. Far from being primitive, they evolved throughout the millenia to the modern sharks we see today, changing the shape and development of their jaws and throat as they evolved from the primitive condition seen in early bony fish into the efficient predators of today. But then, they have been separated from the lineage that led through bony fish up through the early tetrapods all the way to us for over 400 million years. Why would anyone think that in all that time, they stayed still evolutionarily? Even if they look much more similar to their ancestors than we do, they have evolved too. Nothing stays still.

Website Review and the Misconception of a Theory

In a quick review, I would like to discuss the website by Lin and Don Donn, http://earlyhumans.mrdonn.org/evolution.html.

This website is part of a much larger website that is filled with a lot of information on all sorts of history. As Mr. Donn states, they do not claim to be experts in anything, so do not claim everything on the site is correct, although they do try. It is clear they have put a great deal of time and effort into making a substantial site with the honest intention of providing accurate and useful information to teachers. They have won awards for an impressive site. However, in the evolution of humans, they seriously fall down.

The early humans website has several links to good resources. Unfortunately, it has two things that destroy the science educational credibility of the site completely. The first is a link to a presentation teaching Biblical creationism, a subject that has no place in a public school as it is both scientifically invalid and pushes one specific religious view, which is illegal in the United States. Regardless of whether one believes in creationism or not, it is not legal to teach a specific religion in public schools and it is especially not valid to teach that religious view in a science class. The only way to make this legal would be to teach the creationism stories of every other religion equally, without comment as to which one the teacher believed, which would be impossible. Even then, it would have to be in a religious studies class, not a science class. If we are to preserve everyone’s First Amendment rights to freedom of religion, we simply cannot have government-run public schools teach one religious view and we certainly cannot teach that view as a scientifically valid theory. I am hitting this point especially hard because it is a serious point of controversy in the United States, but it should not be. Keeping creationism out of the schools is not an attempt to suppress anyone’s views. It is an attempt to preserve everyone’s right to make their own religious choices without government interference.

That leads me into the second problem, one which is stated boldly right up front. One of the big problems we have in science literacy is that many people do not understand the difference between the colloquial use of the term “theory” and the scientific meaning of the term. To quote the website: “A theory is a guess based on some facts. Remember a theory is not proven. One of the great controversies of our time has been the theory of evolution.” This is massively wrong in two areas.

The term they have defined is NOT a theory. What they defined was SPECULATION. Anyone can come up with an idea, but that does not make it a scientific theory. First, one must have a hypothesis, which is a testable idea, based on observation, that explains a relationship between two or more measurable things. There are two critical parts to this. The observations, so it must be an attempt to explain something we actually see in the real world. Second, that explanation must be testable. If there is no conceivable way to test it, the idea remains in the realm of speculation and can never be taken as a scientific theory, or even a valid hypothesis.

Once one has a series of hypotheses that have been tested by many people, none of whom have been able to disprove the hypotheses, one can formulate a scientific theory. That theory ties the hypotheses together, explaining numerous detailed observations into an explanatory framework that applies broadly. An example of this is the Theory of Gravity. Numerous observations were made showing gravity exists, there is no doubt about that. Many observations showed precisely how it worked and the relationship of different masses to each other, both on earth and in the universe as a whole. However, to make a theory, we needed more than these observations, we needed a way to accurately describe and predict these relationships. Isaac Newton discovered a mathematical equation that could be used to predict the motions of the planets. That equation was then tested many times and found to be valid everywhere, at least at the speeds attained by most things in the universe. Einstein went further with his Theory of Relativity, which extended our understanding of gravity into realms beyond the experience of everyday existence. Even here, these started out as hypotheses, requiring many people to test over and over gain. Not only has no one been able to prove them wrong, but no one has come up with an explanation that better fits the data. Therein lies the key, testing and testing and basing the acceptance of the theory on data, evidence that either supports or disproves the theory. Without that, it is not a theory.

As such, there is no Law of Gravity. We know it exists, it is fact that is undeniable. The Theory of Gravity provides a framework in which gravity works that has been put to the test. In a similar fashion, there is no Law of Evolution. We know it exists, it is a fact that is undeniable. Why? Because the idea that biological life forms change over time is something that cannot be argued against. All one has to do is acknowledge we are not clones of our parents, or look at the diversity of changes brought about by dog and cat breeders, sheep and cow breeders. We see biological change all around us. Evolution is therefore a fact, just like gravity. The Theory of Evolution put forth by Darwin is more properly called the Theory of Natural Selection, which explained this change through the aforementioned natural selection. It has been tested numerous times and shown to work. Is natural selection the only way in which species change? No, but it is a major mechanism. But the point here is that it has been tested and retested. Like all scientific theories, it is not simply a guess based on a few facts. It is permissible to argue about specific mechanisms, but trying to argue whether or not evolution occurs is like arguing whether or not the earth is flat or that we need air to survive.