Today is National Fossil Day™. The National Park Service holds this annual event on the second Wednesday every year to coincide with Earth Science Week sponsored by the American Geosciences Institute. Earth Science Week highlights the important role of earth sciences in our everyday lives and “to encourage stewardship of the Earth.” National Fossil Day is, as NPS says, “held to highlight the scientific and educational value of paleontology and the importance of preserving fossils for future generations.”

Today is National Fossil Day™. The National Park Service holds this annual event on the second Wednesday every year to coincide with Earth Science Week sponsored by the American Geosciences Institute. Earth Science Week highlights the important role of earth sciences in our everyday lives and “to encourage stewardship of the Earth.” National Fossil Day is, as NPS says, “held to highlight the scientific and educational value of paleontology and the importance of preserving fossils for future generations.”

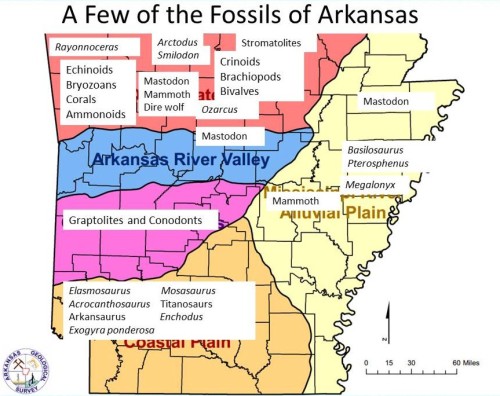

In honor of the day, I am going to give you a whirlwind tour of some of our most outstanding fossils from all over the state. People may not think of Arkansas as being rich in fossils, but we have a rich natural history spanning 500 million years. To give you a quick summary of the wide array of fossils, just check out the map on the fossil page, reproduced below.

Arkansas Geological Survey regional map, annotated with reported fossils.

The most fossiliferous region in the state is the Ozarks, without a doubt. It is a favorite fossil collecting spot for many people, even though much of the area is national forest or national park owned, which prohibits fossil collecting. Nevertheless, fossils may be collected on any roadcut. I-65 near Leslie has several fossiliferous roadcuts. You are most likely to find abundant examples of crinoids, bryozoans like the screw-shaped Archimedes, clams and brachiopods, ammonoids (mostly goniatites), corals such as horn corals and tabulate corals, as well as the occasional echinoid and trilobite, along with many other types of fossils. This list of fossils makes it plain that the Ozarks are dominated by marine deposits, but you can find the occasional semi-terrestrial deposit loaded with plants like Calamites and Lepidodendron.

Top, left to right: Calamites, spiriferid brachiopod, blastoid echinoderm, goniatite ammonoid. Bottom left to right: Archimedes bryozoan, crinoid with calyx and fronds (very rare, mostly you just find pieces of the stalk).

There are a few fossils that particularly stand out. One is Rayonnoceras, a nautiloid ammonoid, which reached lengths of over two meters, making it one of the longest straight-shelled ammonoids ever found. The other is a shark named Ozarcus. While shark teeth are common, it is rare to find one that preserves parts of the skull and gill supports. At 325 million years, Ozarcus is the oldest one like this ever found and it changed the way we viewed shark evolution, indicating that modern sharks may be an offshoot of bony fish, not the other way around.

We can’t leave the Ozarks without talking about Conard Fissure, a spectacular collection of Pleistocene fossils. Barnum Brown excavated the first chamber of the cave in 1906, pulling out thousands of fossils or all kinds, many of which were new to science. Of course, of all of them, the ones that most people remember were 15 skeletons of Smilodon, the largest of the saber-toothed cats. The one pictured to the right is a cast of one from La Brea, California. All of ours are held at the American Museum of Natural History.

We can’t leave the Ozarks without talking about Conard Fissure, a spectacular collection of Pleistocene fossils. Barnum Brown excavated the first chamber of the cave in 1906, pulling out thousands of fossils or all kinds, many of which were new to science. Of course, of all of them, the ones that most people remember were 15 skeletons of Smilodon, the largest of the saber-toothed cats. The one pictured to the right is a cast of one from La Brea, California. All of ours are held at the American Museum of Natural History.

The Ouachita Mountains are not nearly as fossiliferous, but they have two important types of fossils that are commonly found: graptolites (below left) and conodonts (below right, not from AR, Scripto Geologica). Graptolites are thought to be closely related to pterobranchs, which are still living today, even though the graptolites themselves are all from the Paleozoic Era. Most of the time, Graptolites look like pencil marks on slate, but if you find a good one, you can see they are often like serrated files that may come branched or coiled. The reason these are important is because they are hemichordates, the closest group to the chordates, all animals with a spine (either a stiff rod or actual bone). Conodonts, on the other hand, are the closest we have to the earliest vertebrates, looking like nothing so much as a degenerate hagfish.

The coastal plain is quite fossiliferous and has attracted the majority of press because it is here where you will find Cretaceous aged rocks and that means dinosaurs and their compatriots. Here you will find thousands of Exogyra oysters. Scattered among them, you can find numerous shark teeth, along with teeth from Enchodus, the saber-toothed herring (although not really a herring), especially if you look in the chalk beds. You can also find the rare example of hesperornithids, extinct diving birds, as well as fossil crocodilians.

But of course, the main draws here are the marine reptiles and the dinosaurs. Mosasaur vertebrae are not uncommon, although the skulls are. More rarely, one can find plesiosaur (the article only mentions elasmosaurs, which are a type of plesiosaur, but most plesiosaur fossils in Arkansas cannot be identified that closely) vertebrae as well.And then of course are the dinosaurs. We only have a few bones of one, named Arkansaurus, but we have found thousands of footprints of sauropods, the giant long-necked dinosaurs. Since the sauropods that have been found in Texas and Oklahoma are titanosaurs, such as Sauroposeidon, it is a good bet the footprints were made by titanosaurs. A few tracks have also been found of Acrocanthosaurus, a carnivorous dinosaur like looked something like a ridge-backed T. rex. Acrocanthosaurus reached almost 12 meters, so while T. rex was bigger, it wasn’t bigger by much.

Top left: Mosasaur in UT Austin museum. Top right: Plesiosaur vertebra from southern AR. Middle left: reconstruction of Arkansaurus foot. Middle right: statue of Arkansaurus (out of date). Bottom left: Sauropod footprints. Bottom right: Acrocanthosaurus footprint, Earth Times.

The eastern half of the state is dominated by river deposits from the Mississippi River, so the fossils found there are mainly Pleistocene aged, with the exception of a few earlier Paleogene fossils near Crowley’s Ridge. Pleistocene deposits can be found all over the state, as they are the youngest, but are most common in the east. In these deposits, a number of large fossils have been found. A mammoth was found near Hazen, but we have almost two dozen mastodons scattered over the state. I already mentioned Smilodon, but we also have , the giant short-faced bear, dire wolves, giant ground sloths, and even a giant sea snake named Pterosphenus. Most unusual of all is a specimen of Basilosaurus, which despite its name meaning king lizard, was actually one of the first whales. Considering the month, I would be remiss not to include Bootherium, also known as Harlan,s musk ox, or the helmeted musk ox.

Top left: Mastodon on display at Mid-America Museum. Top right: Basilosaurus by Karen Carr. Bottom left: Arctodus simus, Labrea tar pits. Wikipedia. Bottom right: Bootherium, Ohio Historical Society.

This is nowhere near all the fossils that can be found in Arkansas, but it does give a taste of our extensive natural history covering half a billion years. After all, we wouldn’t be the Natural State without a robust natural history. Happy National Fossil Day!

[…] further celebrate National Fossil Day, Paleoaerie has a great article about the fossils that can be found in […]