Mystery Monday

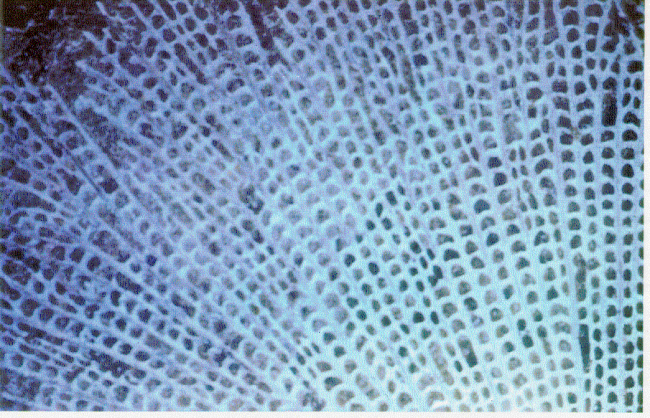

It’s been a very busy weekend, so this will be a very short post. today I simply want to introduce the latest mystery fossil. This is a bizarre little fossil, measuring less than 2 cm across. It’s not the best picture, I admit, but there is enough resolution to identify it to at least the Order. I will post a clue a day until Friday, when I will reveal its identity. Good luck, take a guess, and have fun.

Tuesday’s clue: These teeth are used to eat animals much, much smaller than the animal it came from.

Wednesday’s clue: We are very popular at many aquariums.

Thursday’s clue: Some people say i have wings, but I do not fly. I may have a cold heart, but I don’t bite.

Fossil Friday

It has been a strange week, what with trying to catch up from the holidays and all. So this post will be brief. On Monday, I posted this picture of a commonly found fossil in Arkansas, provided you look in the right places. Here were the clues.

Clue 1: It’s from the Cretaceous.

Clue 2: It’s modern day relatives are widely considered a delicacy.

Clue 3: This is no wilting lily. This creature is big and bold. It shows how twisted it is on the outside for all the world to see. Dude, that’s heavy.

Were you able to figure it out?

So for the final reveal: Exogyra ponderosa. Allie Valtakis was able to figure out it was a mollusc, specifically a bivalve (clam), in the Order Ostreoida, Family Gryphaeidae. While mosasaurs swam the oceans and dinosaurs walked the shores, these Late Cretaceous oysters made huge oyster beds throughout the coastal waters. Like all oysters, they were filter-feeders, collecting microscopic particles of food from the water. You can find them in south-central Arkansas within several rock units, but most particularly in the Marlbrook Marl, a limy mudstone. They are known for their large, heavy, rough bottom shell with a curled, hornlike part near the hinge. The top shell is much smaller and flatter, but still a good size, something like a cap on a coffee cup, if your coffee cup was kind of bowl-shaped. They are sometimes called Devil’s toenails, but that name usually refers to a different clam called Gryphaea, an oyster that is also in the Family Gryphaeidae, but a different subfamily. If you look under a microscope at the shell, you may notice that it is very porous, giving the Family the nickname of foam or honeycomb oysters. Some are still alive today, such as Hyotissa hyotis, the giant honeycomb oyster

E. ponderosa was one of the earliest clams of this genus that was named, by Ferdinand Roemer in 1852, a German lawyer who gave up law to study geology in Texas, thus his title as the Father of the Geology of Texas. You can fossils of them from Texas to New Jersey and Delaware, south through Mexico and Peru.

Until next time, as Dr. Scott The Paleontologist would say, ‘Get out there, get into nature, and make your own discoveries.”

Mystery Monday and Walking With Dinosaurs Movie Review

Mystery Monday

Last Friday I posted clues to a mystery fossil. The clues were 1) I lived in AR during the Mississippian Period roughly 330 million years ago and am a very common fossil to find here. 2) Many people think I’m a coral, but I’m not. 3) I am named after a famous Greek mathematician and inventor. Who, or more precisely, what am I? Allie Valtakis got the right answer as the bryozoan, Archimedes. Here is what the Arkansas Geological Survey says about it.

The Bryozoa grow attached to the sea-floor as do corals, but they differ significantly from corals in terms of soft-part anatomy. The bryozoans are exclusively colonial and fall into two broad groups, the lacy colonies and the twig-shaped colonies. Individual “houses” (zooeciums) lack the radial partitions found in corals, but they are divided transversely by partitions called diaphragms (Fossils of Arkansas). Bryozoans can also grow as incrustations on the shells of other organisms and are commonly associated with reef structures.

“Bryozoans are tiny colonial marine animals that are present in marine and fresh water today. They are sessile benthonic animals (fixed to seabed) that are filter feeders and prefer shallow seas, living fairly close to shore (neritic). One bryozoan called Archimedes (see picture below) is abundant in Mississippian age rocks in Arkansas and is so plentiful that one of the rock formations called the Pitkin Limestone was once referred to as the “Archimedes Limestone”. Generally, only small pieces of bryozoans that resemble “fronds” are preserved in Mississippian and Pennsylvanian age rocks in the Ozark Plateaus Region.

References:

Freeman, Tom, 1966, Fossils of Arkansas: Arkansas Geological Commission

Bulletin 22, 53 p., 12 pls., 15 figs., 1 map.

Way to go, Allie!

Can you guess this week’s fossil? I will do things a bit differently this time. Unlike previous fossils, in which I told people on the Facebook page as soon as someone provided the correct answer, I will not reveal the answer until Friday, so you have plenty of time to give it a try. In addition to the picture (note the scale) below, I will provide one clue every day until Friday. Good luck!

Clue 1: It’s from the Cretaceous.

Clue 2: It’s modern day relatives are widely considered a delicacy.

Clue 3: This is no wilting lily. This creature is big and bold. It shows how twisted it is on the outside for all the world to see. Dude, that’s heavy.

Come back tomorrow for the answer! You can also find it on the Facebook page.

Walking with Dinosaurs 3D movie review

I went to see Walking With Dinosaurs 3D this weekend. My kids were interested in seeing the movie and I liked the BBC “Walking with Dinosaurs” TV mini-series, so we were all eagerly anticipating the movie. I had read a few reviews of the movie, some by paleo people, who said the dinosaurs were great, but the voices were terrible, which gave me pause, but it’s a BBC movie on dinosaurs, how bad could it be, right?

Sad to say, I have to agree with most of the reviewers. This movie may be much more enjoyable if you can’t hear it. To begin with, whatever expectations you may have, forget them. If you are going in expecting to see a big screen version of the BBC “Walking with Dinosaurs,” you will be disappointed by the cartoon voices and plot. If you are looking for light entertainment for little kids, you might be a bit surprised by the rather jarring breaks providing a subpar, documentary-style educational interlude which will kick everyone out of the story.

The film reminded me nothing so much as a cross between the BBC documentary-style series and The Land Before Time movie series, failing at both. I think the reason for this is because it seemed to clearly start off with the idea of it being a kid-friendly movie along the lines of the TV series, but some executive decided after it was made that it was not going to draw enough kids. So the movie was recut and really bad dialogue added to it instead of the normal narration one would expect in a nature documentary, along with completely superfluous modern scenes bookending the film, wasting the talents of otherwise fine actors. The voices were obviously added as an afterthought because the dinosaurs do not act like they are speaking. I could even occasionally hear the original dinosaurian bleating and honking in the background even as they are supposedly talking. The dialogue, as Brian Switek noted in his review, destroyed any emotion that may have been evoked by the scenes that were supposed to be emotionally powerful. What should have been poignant, heart-tugging scenes were drained of any impact by juvenile pratterings that never ceased. I found myself wishing for the dinosaurs to just shut up once in a while. As a result, it is a movie that may be enjoyable for a little kid, but eminently forgettable. Bambi was a much more riveting emotional experience, not to mention more educational about the lives of deer.

The story line was inconsistent with the idea of a nature documentary and a poor choice for a dinosaur movie. Whether or not the worst aspects of it were in the original script, I don’t know, but the final plot, while suitable for a cartoon Land Before Time, was wholly inappropriate for a nature “fauxmentary.” For a film that was supposedly educational, it pushed moral viewpoints which are only valid in human cultural environments and completely invalid in the natural world. The idea that intelligence and courage will overcome the thoughtless, testosterone-fueled belligerence of the larger alpha males is a noble sentiment and may work in a human context, but not in the depicted dinosaur society. Control of a herd of large herbivores that have evolved extravagant displays will never pass to the runt of a litter because he saves the herd in a time crisis due to his quick thinking. The plot line for the movie is far more appropriate to an after-school special involving actual, human children, not dinosaurs. As such, it completely destroys any educational effectiveness of the movie. The only education that remains is that dinosaurs lived in a snowy Alaska and that some dinosaurs had feathers, particularly the smaller theropod carnivores. I really like this aspect of the movie, but its authenticity in these aspects was completely undermined by the silliness of the rest of the movie.

To make it even more confusing in terms of genre plotting, the movie shows that females in the herd are dominated by the alpha male, but glosses over what that means in terms of sexual dominance. In a kid-based movie, this understandably only goes as far as hanging out with each other. In the natural world (and post-adolescent human worlds), as every adult in the audience will understand, it means the female submits to the alpha male’s sexual advances. In terms of a human kid’s movie, it sends very poor messages about the role of females in society. In terms of an educational nature show, it is intentionally misleading to spare the typical parental sensibilities of what is appropriate for kids to see.

In short, if you go to see this movie (which I would really recommend waiting until a rental, as it is not worth spending the price for a 3D movie), go expecting to see a mindless 80 minutes of passable, but forgettable, entertainment for children with no real educational value other than to say look, aren’t dinosaurs neat? Enjoy the graphics, ignore the rest.

Happy New Year! Welcome to 2014

Welcome back! I hope everyone had a great holiday to mark the end of a great year. 2013 marked the inaugural year for Paleoaerie. Version 1 of the website was set up, providing links to a wealth of online resources on fossils, evolution, the challenges of teaching evolution and the techniques to do it well. The blog had 26 posts, in which we reviewed several books and websites, discussed Cambrian rocks in Arkansas and the dinosaur “Arkansaurus,” and went to the annual meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology. We looked at geologic time and started a series on dinosaur misconceptions. We also had several Forum Fridays, recapping the many news stories reported on the Facebook page. One of the recent things we’ve started is Mystery Monday, posting a fossil of the week for people to try to identify. Speaking of which, to start off the new year, the first mystery fossil will be posted early. look for it at the end of this post.

Welcome back! I hope everyone had a great holiday to mark the end of a great year. 2013 marked the inaugural year for Paleoaerie. Version 1 of the website was set up, providing links to a wealth of online resources on fossils, evolution, the challenges of teaching evolution and the techniques to do it well. The blog had 26 posts, in which we reviewed several books and websites, discussed Cambrian rocks in Arkansas and the dinosaur “Arkansaurus,” and went to the annual meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology. We looked at geologic time and started a series on dinosaur misconceptions. We also had several Forum Fridays, recapping the many news stories reported on the Facebook page. One of the recent things we’ve started is Mystery Monday, posting a fossil of the week for people to try to identify. Speaking of which, to start off the new year, the first mystery fossil will be posted early. look for it at the end of this post.

In the upcoming year, we hope to expand the site, providing many more resources, along with continuing posts on Arkansas geology and fossils, including many more mystery fossils. Stick with us and you will learn about the history of Arkansas in a way that few people know. The site will be revamped to be more user-friendly and enticing to visitors. If plans materialize, we will be adding interactive activities, animations, and videos, many of which will be created by users of the site. Materials from workshops and talks will be posted for people to view and use. More scientists will be posted that have offered their services to teachers and students. We encourage you to contact them. They are there as a resource.

Of course, all of this does not come free. it takes money to provide quality services. Thus, more avenues of funding will be pursued, including other grant opportunities and likely a Kickstarter proposal. You may soon see a small button on the side of the website for Paypal donations. Any money donated will go first towards site maintenance. Other funds will go towards a student award for website design, a 3D laser scanner to put fully interactive 3D fossil images on the site, and materials for review and teacher workshops. If grant funding becomes available, additional money will be spent on research into the effectiveness and reach of the project. But even if no more funding becomes available, you can still look forward to continuing essays on Arkansas fossils, reviews of good books and websites, and curation of online resources suitable for teachers, students, and anyone else interested in learning about the endlessly fascinating history of life on planet earth.

I mentioned at the beginning about the latest mystery fossil. Here’s the first hint: it is a very common fossil found in Arkansas and lived during the Mississippian period roughly 330 million years ago. More hints and photos to come. Leave your guesses in the comments section. Don’t worry about getting it wrong, every success has lots of failures behind it. Errors are only stepping stones to knowledge.

Clue number 2: Many people think I’m a coral, but I’m not.

Clue number 3: I am named after a famous Greek mathematician and inventor.

What am I?

Fossil and Forum Friday, Holiday edition

We began the week with our first Mystery Monday for paleoaerie.org with the picture of an interesting Arkansas fossil. Today, Forum Friday will become Fossil Friday as well as we identify the fossil. Did you guess what it was? See if you were right below the picture.

Congratulations go to Allie Valtakis, who correctly identified it as a nautiloid cephalopod. This particular one is Rayonnoceras solidiforme. It has traditionally been placed within the Order Actinocerida, although some workers have placed them into the Order Pseudorthocerida, which is known for their resemblance to the more commonly recognized orthocerid cephalopods.

Congratulations go to Allie Valtakis, who correctly identified it as a nautiloid cephalopod. This particular one is Rayonnoceras solidiforme. It has traditionally been placed within the Order Actinocerida, although some workers have placed them into the Order Pseudorthocerida, which is known for their resemblance to the more commonly recognized orthocerid cephalopods.

What are cephalopods, much less nautiloid cephalopods, you ask? Cephalopods are the group of molluscs that include squids, octopuses, and cuttlefish. There are three major groups: Coleoidia, which includes almost all the modern cephalopods; Ammonoidea, which includes almost all the extinct ones and are known for their complexly sutured shells; and the Nautiloidea, which are mostly extinct, the only living form is the Nautilus. The ammonoids and the nautiloids both formed shells. What differs between them is how they made them. Some of those in Coleoidia also form shells, but they have been greatly reduced and internalized, such as in squids, or lost altogether, such as octopuses. For those with external shells, they have the problem that shells don’t get bigger once the mineral is laid down, so they quickly grow out of their shells. They solve this by adding mineral to the front of the opening in an ever-increasing funnel, periodically walling off the back of the living chamber (leaving a small opening for the siphuncle that goes all the way through the shell, creating a series of gradually increasing sections.

The ammonoids are well known in the fossil record, particularly the subgroup called ammonites, having a diverse array of straight, curved, and coiled shells. What makes them unique from the nautiloids is the sutures between sections are wavy, sometimes showing astoundingly complicated patterns. The nautiloids, on the other hand, sport very simple, smooth curves. It is this group in which Rayonnoceras belongs.

Rayonnoceras lived about 325 million years ago in the Mississipian Period, although nautiloids as a group have been around since the Cambrian Period over 500 million years ago. What makes this particular species so interesting to Arkansans is that the largest nautiloid cephalopod ever found (update: largest pseudorthocerid nautiloid, not largest nautiloid) was discovered near Fayetteville, AR. It was 2.4 m (8 feet) and found in a rock unit named, appropriately enough, the Fayetteville Shale, a unit of dark gray to black shale and limestone, indicative of a warm, shallow marine environment without a lot of sediment input, much like many areas within the Bahamas today.

To recap what we’ve covered over on the Facebook page, we recommended a book discussing misunderstandings in human evolution and another in how evolution affects our health. We saw a hominid fossil hand bone that helped to show how we differed from australopithecines and genetics work that showed us how we didn’t differ from Neanderthals.

We learned how malaria is evolving and why you shouldn’t take medical advice from celebrities. We also bemoaned the airing of a another horrid false documentary about mermaids on Animal Planet.

Emily Willoughby. Wikimedia commons. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license.

We learned about a new dinosaur named Archeroraptor and new work on dinosaurian growth rates. We also read how the largest volcanic eruption ever caused the greatest mass extinction ever.

We read about genetics work that informed us how flowering plants evolved by doubling their own genes and stealing genomes from other plants. We learned about a “second code” within DNA and why the hype was bigger than the story, but may help us rethink our DNA analogies.

We saw how birds defend themselves against cheaters and learned the first lizards and snakes may have given live birth. We also got some information on how teaching and testing will need to change under the Next Generation Science Standards.

On a final note, this will be the last post this year on paleoaerie.org. Enjoy the holidays and join us in January, when we will be embarking on discussion of the Ordovician rocks and fossils in Arkansas. Over the spring, we plan on discussing several vertebrate fossils found in the state. There are several books and online resource reviews coming up as well. We will be adding to our Scientists in the Classroom and adding several new resources to the links pages. As always, we will be posting a plethora of current news items on Facebook, so stay tuned! In the meantime, tell us what you liked, didn’t like, want to see more of, and any questions you may have.

Forum Fridays and Mystery Mondays

Likely thanks to upgrading computer systems and the joys of trying to figure out new setups and operating systems, there seems to have been a small glitch deleting the post that was supposed to go up Friday, so it is getting posted today. So let’s see if we can make lemonade from the lemon.

On Facebook, I started a new set of posts, in which I post a picture of a fossil found in or could be found in Arkansas and see if anyone can identify it. The first one I put up was of a mosasaur, a huge aquatic reptile that swam around Arkansas seas during the Cretaceous Period. People seemed to enjoy it, so I will be doing this on a regular basis. However, it has come to my attention that many places block Facebook, including a lot of schools. So I will be posting them on the blog. I will try to post a new picture every Monday and will then provide the answer on Friday, giving people the week to see if they can come up with the answer. Don’t worry about being wrong, we learn more from our failures than our successes anyway. You can’t win if you don’t play. So with that, let’s play! here is today’s pic. Can you tell me what it is?

In the meantime, if you missed out on all the stuff we covered on Facebook, here is a brief summary of most of hte stories.

Of the many new fossils and work on fossils that were reported on this month, we saw a new fossil primate that may have been ancestral to lemurs and lorises and giant, terrestrial pterosaurs of doom. We learned about the earliest flowering plant in north America, new crests for old dinosaurs and the promise and perils of resurrecting dinosaurs and other extinct animals..

The poor platypus, he has no stomach (but at least he has poison spurs). John Gould. 1863. Wikimedia.

We learned about evolutionary ghosts, how animals colonize new territory, and how unmasking latent variation within a population can lead to rapid evolution.

Photo by Jonathan Blair. http://tinyurl.com/n4xzv26

We learned how evolution made it easier for people to believe in God than accept evolution and why fanaticism of any stripe can lead one astray. We read a discussion about the importance of scientists in science communication, and why we shouldn’t ignore Youtube. We found help in teaching controversial subjects in hostile environments and apps to help teach hard-to-grasp subjects like astronomical distance.

We learned about how bacteria avoid the immune system to cause disease, how they form an important part of breast milk, and the four billion year history of vitamins. We learned even bacteria have a hard time living deep inside the earth and how viruses can kill even antibiotic-resistant bacteria. We also read a review of a book on evolutionary medicine.

Genetics work played a big role in the above stories, but it also gave us the discovery of a second code within DNA and more support for comb jellies being the first animals. We learned why protein incompatibilities make hybrids sterile and how early hominids interbred to form modern humans.So, what were the stories you liked? Did it spark any thoughts, either good or bad? Was there anything that you saw that we didn’t mention? Share your thoughts and don’t forget to try your luck with identifying today’s Arkansas fossil!

Forum Friday, or, hrm, Monday Meetings?

It’s the beginning of December and more than a month since we’ve had a Forum Friday, but since most people were either still enjoying their Thanksgiving dinners or fighting through crowds of shoppers, I opted for a Monday meeting. October was a busy month and November followed suit. Most of what we posted on Paleoaerie since the last Forum was a rundown of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology annual meeting in Los Angeles. A huge amount of material was presented at the meeting, of which we barely scratched the surface. We also reviewed The Big Golden Book of Dinosaurs, a great book for elementary kids.

It’s the beginning of December and more than a month since we’ve had a Forum Friday, but since most people were either still enjoying their Thanksgiving dinners or fighting through crowds of shoppers, I opted for a Monday meeting. October was a busy month and November followed suit. Most of what we posted on Paleoaerie since the last Forum was a rundown of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology annual meeting in Los Angeles. A huge amount of material was presented at the meeting, of which we barely scratched the surface. We also reviewed The Big Golden Book of Dinosaurs, a great book for elementary kids.

We covered a lot on the Facebook page. Evolution in medicine got a lot of attention, including a whole online, open-access journal about it. We learned about evolutionary theory being used in the fight against the flu, malaria, HIV, and cancer, twice, no three times! We even learned why we have allergies, and if that isn’t enough for you, we found a whole series of papers on evolutionary theory in medicine for you.

Studies of human evolution had a good showing this month, starting with a new skull of Homo erectus changing our views of our ancestors and a book called “Shaping Humanity: how science, art, and imagination help us understand our origins.” We learned how women compete with other women and how natural selection can be tracked through human populations.

Modern experimentation has demonstrated how life may have gotten started chemically and how clay hydrogels may have helped. We watched the evolution of bacteria in a lab over 25 years. We also learned how evolution can evolve evolvability.

Evolution outdid itself with deep sea animals eating land plants and an amazing mimicry display. We learned why bigger isn’t necessarily better, why monkeys have colorful faces, and that large canines can be sexy.

In addition to all the news from SVP, we learned about two new giant theropods, the tyrannosaur Lythronax and the allosauroid Siats. We also learned about the toothed bird, Pelagornis and pachycephalosaurs. We also learned about research on what modern animals tell us about dinosaur brains. We also saw evidence that the Mesozoic may not have had as much oxygen as we thought.

Dinosaurs weren’t the only fossils of interest to be announced. A new unicellular organism is providing insights into the evolution of multicellularity. The oldest fossil of a big cat and a suction-feeding turtle were found, as well as the oldest known fossil ever, providing evidence of life almost 3.5 billion years ago. We read the beginning of a series on the evolution of whales and how the first tetrapods crawled onto the land. We learned about fossil giant mushrooms and watched the Red Queen drive mammals to extinction.

Putting 3D images of fossils on paleoaerie has always been one of the goals of the site and the potential for this to revolutionize geology has not gone unnoticed. The Smithsonian has taken up the challenge. If you want to learn how to do it, here is the paper for you.

We celebrated Alfred Russell Wallace and American Education Week. Along the way, we listened to the great David Attenborough describe the history of life and Zach Kopplin tell us about his efforts to keep creationism out of public schools in Louisiana.

For educational techniques and resources, we looked at BrainU and a website by the ADE and AETN. We examined the usefulness and pitfalls of gamification. We saw how to build your own sensors and use them in class. We discussed how to change people’s idea of change through business concepts the truth about climate change. We even saw doctoral dissertations via interpretive dance.

Finally, the holidays are fast approaching, so if you are looking for gifts, we looked at a rap music guide to evolution and Here Comes Science by They Might Be Giants.

Do you have any gift ideas to share? Any of the stories particularly pique your interest? Let us know. Don’t just talk amongst yourselves, talk to us.

It’s Big, It’s Golden, and it’s Dinosaurs

The Big Golden Book of Dinosaurs

By Dr. Robert T. Bakker

Ilustrated by Luis V. Rey

Publication date: 2013. 61 pg.

Golden Books, Randomhouse. ISBN: 978-0-375-96679-8.

Do these books look familiar? One is the classic book that most people old enough to be parents grew up on, first published in 1960 and continuing through 1981. The second is the new, Big Golden Book of Dinosaurs, a new, totally updated edition that came out in 2013. The book is written by Dr. Robert Bakker, known by many as the bushy-bearded, cowboy hat-wearing paleontologist of many documentaries and the author of such books as the Dinosaur Heresies and Raptor Red. Illustrations are by Luis Rey, a talented artist already mentioned here due to his work illustrating Dr. Holtz’s Dinosaurs book. Dr.Holtz’s book was written for a wide audience, geared towards children of middle school age and upwards. This book, like its predecessor, is geared for elementary kids. So it is not as detailed, but it is even more lavishly illustrated and will definitely hold the interest of younger kids.

Do these books look familiar? One is the classic book that most people old enough to be parents grew up on, first published in 1960 and continuing through 1981. The second is the new, Big Golden Book of Dinosaurs, a new, totally updated edition that came out in 2013. The book is written by Dr. Robert Bakker, known by many as the bushy-bearded, cowboy hat-wearing paleontologist of many documentaries and the author of such books as the Dinosaur Heresies and Raptor Red. Illustrations are by Luis Rey, a talented artist already mentioned here due to his work illustrating Dr. Holtz’s Dinosaurs book. Dr.Holtz’s book was written for a wide audience, geared towards children of middle school age and upwards. This book, like its predecessor, is geared for elementary kids. So it is not as detailed, but it is even more lavishly illustrated and will definitely hold the interest of younger kids.

From the front cover to the last page, those who know and love the original book, will find it echoed here, but updated with the latest information. inside the front cover is a map of the world as it existed in the Triassic and early Jurassic, with dinosaurs dotting the landscape, showing where various dinosaurs have been found. The map is matched on the inside of the back cover with a Cretaceous map. Both maps have the names of each of the dinosaurs illustrated so you know what you are looking at. There is also an index and handy pronunciation guide for all the animal names.

While the book is of course heavily weighted towards dinosaurs, like the previous book, it does not focus entirely upon them. In the brief introduction, it makes a point to place the dinosaurs in context as part of an evolving ecosystem, not as isolated creatures. The book then dives into the Devonian seas,introducing us to the fish that began the walk towards becoming landlubbing tetrapods (animals with four legs). It continues with a few pages on the Carboniferous and Permian Periods, with giant insects, early amphibians and reptiles, and even animals like the iconic Dimetrodon, properly identifying its kin as ancestral to modern mammals, even explaining key features showing it’s related to us. Only then do we get to the Triassic, the beginning of the Age of Dinosaurs and even then, it starts the discussion with pterosaurs and the ancestors of crocodylians. After a mention of the earliest dinosaurs, it then mentions the proto-mammals.

Finally, we reach the Jurassic Period and it is here that dinosaurs take center stage, with gigantic, long-necked sauropods and other well-known dinosaurs. Even so, they don’t forget the small, mouse-like early mammals under foot. After a brief interlude to discuss the great sea reptiles that appeared during this time, as well as the pterosaurs, that were now much bigger and diverse than in the Triassic, they return to a discussion of dinosaurs, this time focusing on a bit of history explaining how our views have changed over the decades.

Finally, we reach the Jurassic Period and it is here that dinosaurs take center stage, with gigantic, long-necked sauropods and other well-known dinosaurs. Even so, they don’t forget the small, mouse-like early mammals under foot. After a brief interlude to discuss the great sea reptiles that appeared during this time, as well as the pterosaurs, that were now much bigger and diverse than in the Triassic, they return to a discussion of dinosaurs, this time focusing on a bit of history explaining how our views have changed over the decades.

The book moves then into the Cretaceous, showing how dinosaurs adapted to diverse environments, such as the sand dunes of central Asia to the snows of the poles. There is a chapter on different ways dinosaurs communicated with each other, including singing, after a fashion, much like birds and animals call to each other today, although he goes a bit overboard in this area and speculates beyond what most in the field would say is reasonable. Of course, no elementary book would be complete without a chapter devoted to Tyrannosaurus rex and its battle with an armored herbivore, in this case, the ankylosaurid Euoplocephalus and a battle with Triceratops. While the book makes much of the use of horns and frill by the Triceratops in battling T. rex, they were almost assuredly evolved to battle other Triceratops as dominance displays, like bison or antelope today, although that of course, doesn’t rule out their use as defensive weaponry against predators.

The book moves then into the Cretaceous, showing how dinosaurs adapted to diverse environments, such as the sand dunes of central Asia to the snows of the poles. There is a chapter on different ways dinosaurs communicated with each other, including singing, after a fashion, much like birds and animals call to each other today, although he goes a bit overboard in this area and speculates beyond what most in the field would say is reasonable. Of course, no elementary book would be complete without a chapter devoted to Tyrannosaurus rex and its battle with an armored herbivore, in this case, the ankylosaurid Euoplocephalus and a battle with Triceratops. While the book makes much of the use of horns and frill by the Triceratops in battling T. rex, they were almost assuredly evolved to battle other Triceratops as dominance displays, like bison or antelope today, although that of course, doesn’t rule out their use as defensive weaponry against predators.

There is the required chapter on dinosaur extinction and it does a good job of mentioning several possibilities. However, it gives a bit of short shrift to the most accepted asteroid hypothesis and a bit more space to Bakker’s favorite hypothesis of disease, which is almost assuredly not true as a hypothesis of widespread extinctions on such a large scale. To his credit, he ends with the likely possibility that no one hypothesis is sufficient for explaining everything.

The book ends with what animals actually benefited from the extinction, that being mammals. The book ends with noting that not all dinosaurs died out and acknowledging the influence that dinosaurs had on the evolution of early mammals, thereby connecting the story of the dinosaurs to us. Besides the great illustrations, that I think, is the key strength of this book, never letting the reader forget that dinosaurs were but a part (a big, incredibly impressive part) of a bigger ecosystem, with each piece influencing the others. No group was isolated from the others, all are interconnected.

Overall, while I had a few minor quibbles, as i mentioned above, I can definitely recommend this book for any elementary library. Some middle school kids will like it too, although those older than that will likely be reading it for nostalgia of the original book, who will find this version a worthy successor.

Other than the image of the 1960 book, all images are illustrations from the book.

Day 4 at SVP

Day 4 and the last day at SVP. After this, we will return to our regularly scheduled sorts of posts.Another day of talks and poster sessions, the last chance to meet friends and colleagues and discuss what you’ve heard and what people are doing. Although frankly, I think most people are tired and ready to go home by this point. Some people thrive on the highs of shared creativity and knowledge and find the end of the meeting and going back to regular work depressing, I think the most common reaction is the feeling of being rejuvenated by the meeting, so that you can’t wait to go back and start developing the new ideas created at the meeting, the chance to put those creative juices to work before the distractions of everyday life dry them up.

Day 4 and the last day at SVP. After this, we will return to our regularly scheduled sorts of posts.Another day of talks and poster sessions, the last chance to meet friends and colleagues and discuss what you’ve heard and what people are doing. Although frankly, I think most people are tired and ready to go home by this point. Some people thrive on the highs of shared creativity and knowledge and find the end of the meeting and going back to regular work depressing, I think the most common reaction is the feeling of being rejuvenated by the meeting, so that you can’t wait to go back and start developing the new ideas created at the meeting, the chance to put those creative juices to work before the distractions of everyday life dry them up.

A lot of people don’t like having their talks on the last day. People are going home, they are tired, their attention flags, but this meeting showed a strong turnout for the last set of talks. The symposium scheduled for today was “Patterns from the poles: biodiversity and paleoecology of high latitude fossil vertebrates,” which I, at least, found interesting and worth attending. I didn’t attend too many of the talks though, because there was also a session on the evolution of early birds, which I found even more interesting, as well as a session on mammals, which had several talks discussing how different mammal groups adapted to climate change in the past. Several talks introduced new fossils and what they contributed to our knowledge of evolution within those groups, such as a new Devonian fish from Siberia, the first pterosaur from Antarctica, a new sauropodomorph (early versions of animals that would become sauropods, the oldest mammal from Antarctic and a new Arctic camel, new birds, seals, sirens, dolphins, and whales. All in all, good reasons to stick around.

Rui Pei reported on a new specimen of Anchiornis, the first animal in which fossil evidence in the feathers was used to determine coloration. Anchiornis lived 10 million years before Archaeopteryx and there has been some debate about whether it was a true bird or still a non-avian dinosaur. Pei’s analysis of the new specimen indicated that Anchiornis was a troodontid, so not quite yet a bird. This is another great example that the transition between birds and other dinosaurs is so well documented that the line is an arbitrary classification with no biological relevance. Speaking of feather colors, William Gearty found new ways to study the melanosomes in the feathers providing colors, finding that, in addition to color, he could tell color gradients as well. he also concluded that melanosomes stiffened the feathers, making them more resistant to wear, but also carried more bacteria, thus representing an additional resource cost for the animals (some of this work can be found online at PLOS One).. Justin Hall found that feather asymmetry, long thought to be important for flight, turned out not to have the aerodynamic significance we thought, as it didn’t really affect the ability to fly. Ashley Heers found trade-offs in locomotor ability: the more investment in wings, the less was put into the legs, and this trade-off could change as the bird grew so that chicks may emphasize the wings or legs while the adults emphasized the other.

Several studies showed the difficulties inherent in paleoecology interpretation. Peter Makovicky found that the horned ceratopsids showed different growth rates between northern and southern populations, the duck-billed ornithopods did not, and the carnivorous theropod Cryolophosaurus showed different growth rates in different areas of the same body in the northern individuals, but not in the southern individuals. According to Bergman’s rule, we should expect to see animals get bigger and stockier the farther north they are found. Anthony Fiorillo found that the small troodontids followed the rule, but northern individuals of the large tyrannosaurs were only 40% the size of the southern ones. In this case, it is likely that resource supply kept the tyrannosaurs smaller. Patrick Druckenmiller reported on a diverse Arctic dinosaur fauna including toodontids, dromaeosaurs, thescelosaurs, hadrosaurs, pachycephalosaurs, and tyrannosaurs, despite mean annual temperatures near freezing. While similar to southern forms, all the species were different, indicating a discrete, provincial ecosystem. John Tarduno argued that the presence of champsosaurs (a type of early crocodylian) and turtles indicated the weather was too warm for ice to be present even during winter, but as proven by an earlier talk, we know this is incorrect (a great example of science correcting itself). He proposed volcanism forming a series of shallow, freshwater connections between North America and Asia during the latest Cretaceous allowing interchange between the continents, which will need more study to determine if that proposal is true. Judd Case found that even though modern fish fauna show a drop in diversity with lower temperatures, thisi was not the case in the Cretaceous. As the temperature in the Cretaceous dropped 8-10 C in the Antarctic oceans, the fish didn’t really change, although marine reptiles increased in diversity while the ammonite diversity dropped.

Rodrigo Figueiredo presenting evidence that predators who pursue their prey (as opposed to ambush predators attacking large prey and those that pounce on smaller prey) may not have evolved to go after herbivores, but to prey on the pounce predators themselves, much like wolves will sometimes hunt foxes and weasels. Michael Greshko presented a study finding that herbivores known as generalists (able to eat a wide variety of plants) mostly consist of different individual specialists who eat only a narrow range of foods. This is rather like why a pizza buffet needs to stock a lot of different types of pizza even though any particular customer may only eat one or two different types. Speaking of eating, Emily Rayfield gave a possible answer to why mammals reduced the number of bones in the mandible to just one, as opposed to having several bones in the lower jaw like other groups of animals. Using Finite Element Analysis, an engineering method designed to test mechanical strength of materials, found that the one bone provided a stronger bite while reducing stress. Alistair Evans used a program called GEOMAGIC to study tooth shape in early mammals and predict what tooth shape should be like to help sort out all the isolated teeth for which we have no idea what they belong to. in this way, he is making predictions of fossils that have not yet been discovered.

In addition to the software programs mentioned previously, several others were mentioned in talks this day. Most biogeography methods these days are done using phylogenetic methods to help inform how animals spread out across the globe, but Chris Sidor presented Bipartite Occurrence Networks (BON), using Gephi to visualize the patterns, which just uses locality connectedness and found that therapsids (proto-mammals, aka mammal-like repties) were pretty widespread and cosmopolitan before the Permian extinction event, but became much more provincial and limited in range afterwards. Paul Upchurch used TREEFITTER to map pterosaur biogeography, finding support for sympatry (speciation within the same region) with an origin in eastern Asia. Diego Pol used Ancestral Area Reconstruction methods to conclude that dinosaurs probably originated in South America, along with most, but not all, mammals, but crocodylamorphs originated in China. Graeme Lloyd used GEIGER to study evolutionary rates and Akinobu Watanabe used PERDA (Polymorphic Entry replacement Data Analysis, a script running in TNT, a phylogenetics analysis program) to simulate poor sampling of phylogenetic data, finding that if a trait, or character, has multiple possibilities within a single species, it seriously messes up results unless multiple individuals covering all the possibilities are included in the analysis. John Alroy found that no current method is very good for finding the first appearance of taxa, but Bayes Theorem methods, such as used in MrBayes, produce better estimates of extinction times.

The last two talks I would like to mention are from Robert Sansom and David Grossnickle. Sansom found that loss of soft tissue characteristics resulted in changes in cladograms drawn from the data for vertebrates, but not for invertebrates. In other words, if one only looked at hard parts, the evolutionary relationships changed, and more often than not, made the animal appear to be more ancestral than it really was. This occurred even if the characters were recorded as unknowns and not simply listed as absent. Grossnickle looked at morphological disparity in Mesozoic mammals, i.e. the diversity of body form. What he found was that most Mesozoic mammals were carnivorous/omnivorous, with a low level of diversity which gradually increased until the middle Cretaceous. At some point in there, they hit a botttleneck. Their diversity crashed and, while it did start going up again,never reached the previous diversity levels until after the K-T extinction event. What is interesting about this is that pretty much everything else was diversifying, while mammmals were not. Another interesting thing about this is that according to molecular data, mammals were diversifying, so the apparent diversification did not show up as morphological diversity.

This is the end of my discussion about the science presented at SVP. There were so many more talks and posters that I did not mention and i make no claim that the ones I mentioned are even the best or most important, nor are they even all the ones I attended and learned something from, but it would take me until the next meeting to discuss all of them. The point is that meetings like this are incredibly fascinating places to see what is going on in science right now. Anyone who thinks science is a bunch of stale facts in textbooks or that scientists even pretend to have all the answers is seriously mistaken. The search for truth is asymptotic, you can get ever closer to a totally clear understanding of reality, but you will never reach it. Science is all about going over the data, tossing out ideas that don’t succeed and developing ones that do, with each step opening up new avenues of exploration.

I will end this discussion with the awards banquet held on the evening of the last day. During this banquet, we are told how much the auction collected to support the society, important news, memorials for those we lost recently, and people are recognized for their hard work and contributions to the field of vertebrate paleontology. Students are awarded their prizes and scholarships they have won, artists are awarded for best art in different categories, and people are recognized for outstanding careers that have progressed the field. This year, one of the biggest awards went not to a scientist, but to a science advocate. Perhaps because the meeting took place in Los Angeles, special recognition went to Steven Spielberg, for the money he has donated to the Jurassic Foundation and other places to support paleontology research and education and for the Jurassic Park movies, which brought paleontology to the center of the public eye and has inspired many to enter the field and make their own contributions. Officially, the meeting ended here. There was an after-hours celebration, which is always fun from what I hear, but I was beat and had a plane to catch early in the morning, so I called it a day. Until next year!

Day 3 at SVP

Another day at SVP, another boatload of information. Some may be wondering why I am devoting several posts to this meeting,when it may seem not as relevant to the general public. Fair question. people not actually doing science in an academic setting rarely get a chance to see anything about what it is like. Science is often presented as a list of facts, but that is only part of the story. Science is a dynamic endeavor, never being satisfied with an answer, always working on the things we don’t know and revisiting the things we thought we knew to see if they still hold up under the new information. Science gets things wrong all the time, but this process of study and review and critical examination reduces the margins of error. Not all things that are wrong are equally wrong, rejecting evolution in its totality is a whole other category of wrong compared to disagreements about the rates of evolution in a particular lineage. No one in science who examines the evidence seriously disputes evolution or that dinosaurs existed, but exactly how evolution works, how dinosaurs lived, exactly who is related to whom; these are questions that people struggle with. With each new study, the path moves closer and closer to the truth, each time having the possibility of opening up whole new avenues of exploration we had never thought of before. That is what these meetings are all about, bringing minds together for new solutions to old questions and for finding new questions to ask about old solutions. What goes on at meetings is a glimpse behind the curtain of published papers and distilled textbooks, putting human faces onto that quest, faces that are, more often than not, students working together and with more experienced people. Most science is done not by white-haired old men in the lab, but by young, energetic students with a zest for learning. And there is so much more to do.

Another day at SVP, another boatload of information. Some may be wondering why I am devoting several posts to this meeting,when it may seem not as relevant to the general public. Fair question. people not actually doing science in an academic setting rarely get a chance to see anything about what it is like. Science is often presented as a list of facts, but that is only part of the story. Science is a dynamic endeavor, never being satisfied with an answer, always working on the things we don’t know and revisiting the things we thought we knew to see if they still hold up under the new information. Science gets things wrong all the time, but this process of study and review and critical examination reduces the margins of error. Not all things that are wrong are equally wrong, rejecting evolution in its totality is a whole other category of wrong compared to disagreements about the rates of evolution in a particular lineage. No one in science who examines the evidence seriously disputes evolution or that dinosaurs existed, but exactly how evolution works, how dinosaurs lived, exactly who is related to whom; these are questions that people struggle with. With each new study, the path moves closer and closer to the truth, each time having the possibility of opening up whole new avenues of exploration we had never thought of before. That is what these meetings are all about, bringing minds together for new solutions to old questions and for finding new questions to ask about old solutions. What goes on at meetings is a glimpse behind the curtain of published papers and distilled textbooks, putting human faces onto that quest, faces that are, more often than not, students working together and with more experienced people. Most science is done not by white-haired old men in the lab, but by young, energetic students with a zest for learning. And there is so much more to do.

In the previous two days, there were collections of talks called symposiums, devoted to specific topics, such as on ontogeny and the la Brea tar pits, including a preparators symposium on fossil collection and preparation techniques. Friday included a special symposium on the tempo of evolution and dating the fossil record. Samuel Bowring presented the EARTH-TIME Initiative, an opportunity to date the stratigraphic record to a precision never before seen, allowing measurements as refined as +/- 20,000 years all the way back to Triassic times (>200,000,000 years ago). That is a resolution of 0.01%. The remaining talks were about research on specific areas and times contributing to that increased precision.

Tar pits at the Page Museum. http://www.tarpits.org

Terry Gates looked at cranial ornamentation in theropod dinosaurs, finding only larger theropods used bony ornamentation and that if a lineage developed it, the lineage quickly developed larger species. So the question now is why were bony cranial ornaments only selected for larger body sizes? Yuong-Nam Lee reported on new fossils of Deinocheirus, an enigmatic fossil previously known only from one set of huge arms, which allowed them to determine it was the largest ornithomimosaur ever found, sporting a large sail on its back near the hips, something like a small spinosaur sail. Picture a giraffe-sized ostrich, with a sail on its back, giant arms with huge claws, and a big,chunky tail. On second thought, maybe not so much like an ostrich, after all.

Other dinosaur reports include Ashley Morhardt, who reported that Troodon had the largest encephalization quotient of any non-avian dinosaur (i.e. it had a big brain). Most of its brain was made of the cerebrum, which not only makes a reasonable case for it being the smartest dinosaur, but supports a mosaic model of brain evolution, meaning that different parts of the brain evolved at different rates. Amy Balanoff discussed the evolution of oviraptorosaur skulls and brains, showing larger cerebrums than most other dinosaurs, but reduced olfactory tracts, so they were similar to birds in having a relatively poor sense of smell. Walter Persons reported on fossils showing that Microraptor ate mostly fish, as well as small mammals and birds.

A session devoted to mammals had several interesting talks, such as one by one by Ross Secord, who concluded from his research that the body size increase seen in horses was related to warmer temperatures allowing an longer growing season causing increased availability of grasses, making up for the lesser nutritive value of grasses compared to other plants. I would argue however, that a shift to eating hard-to-digest grasses would result in increased body size not through increased availability, but to increase digestion efficiency. Horses are what is known as hind-gut fermentors, which is less efficient than the foregut fermentation seen in ruminants such as cows. This mode of digestion is more efficient at higher body sizes, allowing more time for digestion. Lindsey Yann found that horses were too much of generalist feeders to be useful for paleoclimate reconstructions, but different camel species were more specialized and could used to make determinations of relative aridity and plant cover. Rebecca Terry found that interactions between mouse species had at least as large an effect on population sizes as climate, with different species reacting differently to resource changes. Thus, there is no easy answer to predicting how species will react to climate changes because they cannot be looked at without understanding interactions throughout the entire ecosystem. Much of this sort of work uses MIOMAP and FAUNMAP, which are similar paleontology databases to the Paleobiology Database, but limited to mammals in North America and so may be more complete for these types of studies.

Brady Foreman discussed ways to interpret the completeness of the fossil record based on river deposition patterns and Patrica Holroyd discussed the “missing marsupial problem,” finding that because most eutherian mammal fossils are identified to species level and most marsupial fossils cannot identified beyond “marsupial,” there is a taxonomic identification bias in the literature and thus, species diversity studies.

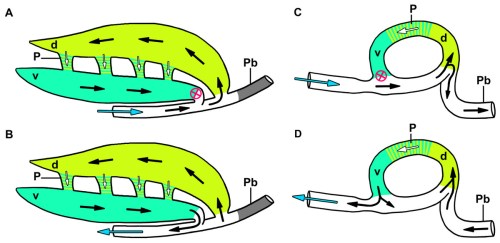

Three other studies I would like to mention are about archosaurs, the “ruling reptiles,” including crocodilians, dinosaurs, and birds. Brandon Peecook looked at the bone microsturucture of Nyasaurus, which was either the earliest known dinosaur or the closest basal archosaur to it, and found that it had elevated growth rates compared to other reptiles, indicating that all dinosaurs may have had faster growth rates from the beginning. John Sarrazin reported that crocodilians and birds both use unidirectional air flow through lungs,as opposed to bidirectional like mammals, which uses a completely aerodynamically controlled system with no structural valves, so in all likelihood, the ancestral archosaur had these characteristics as well. Finally, Jennifer Nestler found that cold weather is not what limits the range of alligators. Rainfall contributed more than 60% to range limitations, most of the rest comes from warm weather during the summer providing long breeding seasons. Only 0.4% of the factors limiting their range could be attributed to cold weather limitations. Something to think about as global warming causes longer summers with elevated rainfall in the eastern United States.

At the end of the day, after the talks and the poster sessions, this is the day for the annual auction, to raise funds for the organization that can be used to fund research and travel grants for students in the upcoming year. The auction consists of two parts, a silent auction and a live auction. In the silent auction, everyone has two hours on which to bid on the objects they want and the last bidder wins, much like alive version of eBay. The auction is filled with a wide array of donated items, everything from rare books and artwork to hand-knitted dino-themed baby socks, whatever people are willing to donate. After the silent auction comes the live auction, usually filled with more expensive, one-of-a-kind items, such as original artwork or the original copy of O.C. Marsh’s dinosaur monographs. I have even seen the services of a field cook and her personal field kitchen for a season get auctioned off. The auctioneers always have fun with it, usually dressing up in costumes. you never know who is going to be serving as auctioneer, it could be a zombie, King Tut, or Superman, but regardless, it is an entertaining spectacle.

An end to another day, only one more day to go, before everyone packs up to go home, or off to their next meeting, or a museum to do research, wherever their path leads them.